Is it your New Years’ resolution to cook more in 2021? Is lockdown forcing you to spend more time in the kitchen? Are you just tired of eating the same dishes over and over again? From solo feasts to fantasy dinner parties, here are eleven brilliant cookbooks by sapphic chefs to make your meals as queer as possible.

Flavour by Ruby Tandoh

Flavour by Ruby Tandoh

If you’re a fan of The Great British Bake Off, Flavour from Season 4 runner-up Ruby Tandoh is the perfect match for you. Organised by ingredient, the cookbook is a great way to follow what you have in the fridge to a brand new recipe – some sweet, some savoury. Tandoh also writes delightful anecdotes about the inspirations behind her meals, including a spaghetti dish dedicated to Adèle in Blue is the Warmest Colour, and the Dutch Baby dessert which is (allegedly) a favourite of Harry Styles.

Now and Again by Julia Turshen

Now and Again by Julia Turshen

Fed up with food waste? I know I am, but working out how to use up that half-a-shallot sitting at the back of my fridge is a source of constant stress. Thankfully, Julia Turshen’s Now and Again will inspire you to stop worrying and embrace your leftovers. The accessible, affordable recipes are accompanied by notes on how to prep in advance and handy tips on what you can do to repurpose any remaining food. For cooks of all skill levels, these are staple recipes that you’ll find yourself returning to again and again.

A Simple Feast by Diana Yen and The Jewels of New York

A Simple Feast by Diana Yen and The Jewels of New York

As beautifully designed as it is informative, A Simple Feast features gorgeous photography from Diana Yen and her creative studio The Jewels of New York – who unsurprisingly specialise in food styling. Split into four seasons, the recipes are arranged by situational themes such as ‘Brown Bag Lunch’, ‘Snow Day’ and ‘Rooftop Barbecue’. It’s a charming way to navigate a cookbook, and to bring a little New York fantasy and glitz to your kitchen.

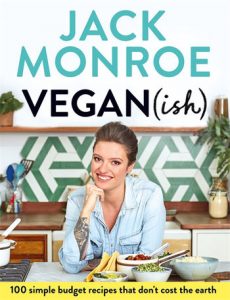

Vegan(ish) by Jack Monroe

Vegan(ish) by Jack Monroe

Are you trying to eat fewer animal products this year? Known for their shoe-string budget recipes, food writer and anti-poverty campaigner Jack Monroe has the answer in Vegan(ish). Not only are these plant-based recipes a great way to cook on a budget, they also help to reduce your environmental impact, whether you’re taking the vegan plunge or just bored of eating steak for every meal (er, you probably shouldn’t be doing that anyway!). Another bonus are the deliciously punny recipe titles, such as Beet Wellington and Chilli Non Carne.

Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen by Zoe Adjonyoh

Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen by Zoe Adjonyoh

Based on the pop-up restaurant of the same name, Zoe’s Ghana Kitchen celebrates – you guessed it! – Ghanian cuisine. Part memoir, part cookbook, the recipes trace Adjonyoh’s heritage through food, from traditional dishes to ways to incorporate flavours into contemporary dishes. The book also includes a guide to sourcing ingredients – another passion of Adjonyoh’s, who has spent the past year focusing on how to decolonise the supply chains, farming and agriculture systems that export spices and produce from the African continent.

My Drunk Kitchen Holidays by Hannah Hart

My Drunk Kitchen Holidays by Hannah Hart

Not confident in the kitchen? With helpful instructions such as ‘take a drink!’ and ‘post it to Instagram’, the recipes in My Drunk Kitchen Holidays are well-suited to even the most amateur of cooks. If you’ve ever watched YouTuber Hannah Hart’s My Drunk Kitchen series, then you’ll know what to expect from her cookbooks: chaotic hilarity. This one covers a year of holidays and observances, from New Year’s to Middle Child’s Day (apparently that’s a thing!); ideal for a time when finding anything to look forwards to is a blessing.

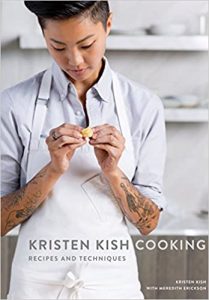

Kristen Kish Cooking by Kristen Kish and Meredith Erickson

Kristen Kish Cooking by Kristen Kish and Meredith Erickson

When you want to cook something a little more ambitious, Season 10 Top Chef winner Kristen Kish is a great person to turn to. Her mouth-watering recipes are accompanied by personal anecdotes and notes, and preceded by a soul-bearing introduction that delves into Kish’s childhood and later experience on Top Chef. While some of the ingredients may be tricky to come by, the dishes have a ‘wow factor’ for when you really want to show off your skills.

Repertoire by Jessica Battilana

Repertoire by Jessica Battilana

Although it’s exciting to cook new dishes, it’s also useful to have some tried-and-tested meals that you can create while running on auto-pilot. In Repertoire, Jessica Battilana shares the 75 recipes that she relies on most. From Garlic-Butter Roast Chicken to a dependable Chocolate Cake, these are simple, accessible dishes that don’t require years of practise to master.

Atelier Crenn by Dominique Crenn

Atelier Crenn by Dominique Crenn

At the opposite end of the scale, Atelier Crenn is the daunting cookbook from three-Michelin-starred chef Dominique Crenn. Crenn’s dishes are ambitious, inventive and beautifully artistic. While I’m not brave enough to attempt such lofty recipes as Sea Urchin with Licorice or Beef Carpaccio, I’m happy for colleagues to think that I am when they spot it on my bookshelf during a Zoom.

Solo by Anita Lo

Solo by Anita Lo

Now more than ever, living alone can be tough, and it’s often hard to find motivation to cook if it’s just for yourself. Luckily, Anito Lo is here to help with Solo, a recipe book bursting with meals for one. The book is structured like a restaurant menu, with sections on vegetarian meals, noodles and rice, fish, poultry, meat, sides and sweets – there’s truly something for every taste. Practise a little self-care this year and treat yourself to some delicious solo meals!

The Little Library Cookbook by Kate Young

The Little Library Cookbook by Kate Young

If you’re reading this article, you’re probably a book-lover as well as a foodie. Featuring 100 recipes inspired by literature, The Little Library Cookbook is a perfect combination of these two passions. Sample Paddington’s marmalade, bake cookies with Merricat, or – for something extra sapphic – dine with Virginia Woolf in a room of one’s own.