Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link I will be completely honest—I really do not care very much for The Great Gatsby. This book, however, far exceeds its source material (*gasp* sacrilege!). This is everything I want out of a retelling of a classic novel, and I am so glad I read it. Nghi Vo’s The ChosenRead More

Maggie reviews Wild and Wicked Things by Francesca May

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link With a frenetic, Roaring Twenties-type vibe, Wild and Wicked Things by Francesca May is set in a post-WWI society where half of society is trying desperately to recover from the devastation of the Great War, and the other half is trying desperately to party hard enough that they forget thereRead More

Susan reviews The Elusive Mr Vanderbridge by Cat Parra, Erica Chan, and Zora Gilbert

Clement Vanderbridge is acting suspiciously; he’s a well-known architect in prohibition-era New York and famously teetotal, but disappears every Friday night only to turn up smelling of alcohol and cigarettes. Fortunately, Stella Argyle and Flora Fontaine are on the case – reporters working for rival newspapers, competing for the scoop. Or, to put it anotherRead More

Carolina reads The Chosen and the Beautiful by Nghi Vo

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Buckle up, old sport! The Great Gatsby has entered the public domain, leaving the door open for any author to submit their take on Fitzgerald’s classic. A myriad of sequels, prequels and retellings of the novel have already been published in 2021, or are slated to be releasedRead More

Shannon reviews Dead Dead Girls by Nekesa Afia

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link In Dead Dead Girls, the first installment in Nekesa Afia’s Harlem Renaissance series, readers are introduced to Louise Lloyd, a black lesbian with a troubled past. The year is 1921, and Louise is working at a small cafe to keep a roof over her head. She spends herRead More

Anna Marie reviews Women Lovers, Or the Third Woman by Natalie Clifford Barney

Women Lovers or the Third Woman by Natalie Clifford Barney is an intense and poetic modernist novel about three women (N, L and M) deeply devoted and in love with each other, and chronicles the transformation of their relationship. The idea of the “Third Woman” is not only a reference to one of the women inRead More

Marthese reviews Silhouette of a Sparrow by Molly Beth Griffin

“Isabella was joy and excitement and adventure and everything else seemed dull in comparison” Silhouette of a Sparrow is set in 1920s America and follows the story of Garnet. I had been meaning to read it since it came out; the chapters of the book all feature a different bird which is a quirky conceptRead More

Danika reviews Orlando by Virginia Woolf

Orlando is the book that I’ve been most ashamed of never having read. It’s a queer classic! So when I was picking out which book should be my first read of 2016, it seemed the obvious choice. The funny thing about reading the classics is that I always go in thinking that I have a generalRead More

Laura reviews All We Know: Three Lives by Lisa Cohen

Much as I despise cold weather, there’s something really wonderful about the rituals of early autumn. You pack up your shorts and sundresses. You begin wearing scarves and boots. You convince yourself that flannel is fashionable outside the lesbian bar. You slurp Oktoberfest ales every evening, and pumpkin spiced lattes every morning. You reach forRead More

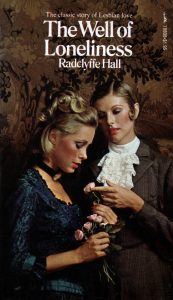

Danika reviews The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall

Whew. I finally finished reading The Well of Loneliness. This isn’t the first time I read it, but when Cass of Bonjour, Cass! suggested we read it for pride (finished a little late), I was all for tackling this classic lesbian tome. Once again, I must reiterate: don’t let this be the first lesbian bookRead More