Bookshop.org Affiliate Link In their debut novel Chlorine, Jade Song (she/they) draws upon her twelve years of lived experience as a competitive swimmer to craft the dark and complex inner world of Ren Yu, a Chinese American teenager coming of age in Pennsylvania and stepping—or rather, swimming—into her true destiny: becoming a mermaid. While Song is clearlyRead More

10 of the Best Sapphic Mermaid Books

For Pride month, the Lesbrary has posts going up every day in June! Today, we’re celebrating bi and lesbian mermaid books (plus a bonus couple of selkies). Each of these books have gotten a glowing from Lesbrary reviewers, which are linked if you want to learn more about any of these! They range from literaryRead More

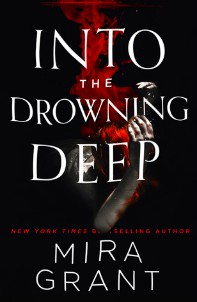

Mo Springer reviews Into the Drowning Deep by Mira Grant

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Seven years ago, the voyage of the Atargatis ended in death, tragedy, and mystery. The ones left behind, watching the footage from their conference rooms and research labs, can only do thing to avenge the death: solve the mystery. Are there really mermaids in the Mariana’s Trench? WillRead More

Shana reviews The Deep by Rivers Solomon

The Deep is the most beautiful book that I’ve read this year. It’s a lyrical novella based on a Hugo Award-nominated science-fiction song by clipping, a hip-hop group. The Deep is a reimagined mermaid story about an underwater society descended from African women tossed overboard during the transatlantic slave trade. We learn about the cultureRead More

anna marie reviews Salt Fish Girl by Larissa Lai

Salt Fish Girl by Larissa Lai is a gooey treat of a book, full of nauseating smells, intoxicating feelings and so much juicy/murky/enticing fluid. In other words it was really great, even better than The Tiger Flu (2018) in my opinion, which I read last year and enjoyed immensely too. Both novels in fact shareRead More

Sash S reviews The Gloaming by Kirsty Logan

“Let the sea take it.” The Gloaming begins with jellyfish washing up near a cliff by the sea, on an island where the residents die slow deaths by turning to stone. It’s a sad, strange and beautiful scene, just one of many sprinkled throughout this novel. Our protagonist is Mara, who falls in love with Pearl,Read More

Danika reviews “The Freedom of the Shifting Sea” by Jaymee Goh

New Suns is an anthology of speculative fiction by people of colour, and it does include a few queer women short stories, but one really stood out to me: “The Freedom of the Shifting Sea” by Jaymee Goh. The author describes it as “A pornographic triptych of three different individuals encountering a creature part human,Read More

Megan G reviews Surface Tension by Valentine Wheeler

Sarai thinks she’s found the adventure she longs for when she finds a job as a crew member of a ship. Before her adventure can end, however, a storm throws her overboard and separates her from the ship. When she awakes on the shore of her homeland, there is a week-long gap in her memory,Read More

Danika reviews Into the Drowning Deep by Mira Grant

I found Into the Drowning Deep because I was looking for deep sea fiction. I’ve had an interest in the deep ocean since I was a kid, and I was craving a book to satisfy that itch. Throw in some killer mermaids, and how I could resist giving this one a go? It wasn’t until after IRead More

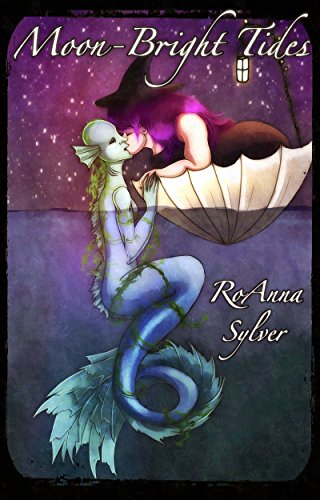

Shira Glassman reviews Moon-Bright Tides by RoAnna Sylver

First of all, do I really need to say anything other than “sweet romance novella between a witch and a mermaid” in the first place? But I have lots more to say about Moon-Bright Tides by RoAnna Sylver, which rocketed to the top of my f/f fantasy recs list as soon as I read itRead More