Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary!

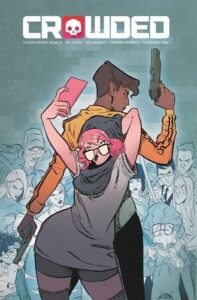

The Crowded comic book series tells the satirical story of a dystopian world not too far in the future where the gig economy has become unhinged. In this world, everything has a price, including putting out hits on someone’s life through an app called Reapr. Anyone can be a target and anyone can crowdfund a kill, and loopholes in technology laws make it easy to get away with it while law enforcement and government officials look the other way.

Following the antics of Charlie, the hit in question, and her hired protector, Vita, the story unfolds into outrageous mayhem. It all seems so farfetched, yet in light of our reality, perhaps it’s not too far off target. Live streamers become famous for their Reapr kills and their followers can become patrons of their feeds for exclusive content and other rewards.

The vibrant and oversaturated artwork lends itself well to the story and characters. It creates a sense of inauthenticity and fabrication that makes everyone so fake. It feels fitting that the story takes place in Los Angeles, infamous for being filled with disingenuous people. It also adds to the fast-paced action as Charlie and Vita fight their way out of sticky situations (caused by Charlie’s reckless choices).

Neither Charlie nor Vita are likable characters, but Charlie especially makes it hard to root for her as a heroine. Despite her constant careless behavior and terrible treatment of others, including her bodyguard Vita, she has moments of humanity and vulnerability that make you not want to give up on her. But much like Vita, you also can’t trust her. Their bickering dynamic points the story toward these two possibly getting together. However, the shared moments in this first volume feel forced, so it doesn’t seem like that relationship has been earned yet.

Charlie is openly and unapologetically bisexual. She has no problem talking about her many conquests, man and woman alike. There’s even a sequence at a club called Bifurious where the artwork is entirely done in “bisexual lighting” in case it hasn’t been made clear until then. She flirts shamelessly with Vita, which Vita doesn’t directly engage in at first, but she doesn’t discourage it either.

Vita is revealed to have had an ex-girlfriend in the police force, making her solidly sapphic. However, it hasn’t been made clear or stated outright that she is a lesbian. As the story progresses, she gets close to Charlie, and it’s hard to tell if she flirts with her client to gain her trust or if she genuinely likes her.

Overall, this first volume is a fun and zany read. And the plot twist at the end (which I won’t spoil here) left me wanting to find out what happens next.

Content warning: extreme violence