Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link

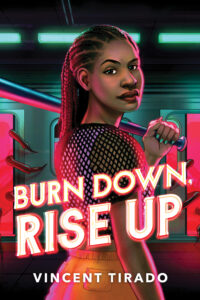

I have to say, although I love the illustration of Raquel, I don’t think cover does justice to this being a horror novel. I got sports vibes from it. I didn’t notice the little monster claws/legs in the background on first viewing. But this is definitely horror, with some blood and gore, so be prepared for that going in.

This is a YA horror novel about a nightmare version of the Bronx where people are infected with mold until it consumes them, where fires burn endlessly, and where giant centipedes roam the streets and eat anyone they can catch. It’s bloody and has some serious body horror. But it’s also about the history of the Bronx, the racist policies that led to real-life horrors, and what it takes to try to rebuild when the fires still aren’t completely out.

People keep disappearing from the Bronx, and even the white teenagers who get a full police investigation aren’t found. It’s just background noise in Raquel’s life, until one day her mother goes into a coma after coming in contact with a patient covered in strange mold who then fled. Her crush, Charlize, confides in her that she saw her cousin Cisco before he disappeared, and he was covered in that same mold. If he was the one who infected Raquel’s mother, maybe finding him will be the key to helping her.

Aaron, Raquel’s best friend who also has a crush on Charlize (Awkward.), agrees to help, and the three of them try to research what happened to Cisco. Meanwhile, Raquel has started having disturbing visions and dreams, including one that leaves her with a burn on her skin. After going down some Reddit rabbit holes, they learn about the Echo game, also known as the Subway game. It involves going into the subway tunnels at exactly 3 A.M. and chanting, “We are Echobound.” The rules are strict, and it’s said that if you break them, you will never come back. Forums online are full of people’s stories of this Echo place, a nightmare version of their city.

The Echo game sounds a lot like the sort of creepypasta horror stories that get passed around Reddit and other forums, with just enough specificity to have you questioning whether they’re real or not.

Between a school assignment and the Echo research, Raquel learns about the darkest time in the Bronx’s history, which is taken to the extreme in its Echo. She learns about the racist policies that led to low income houses burning down constantly, killing many residents. She identifies the villain at the centre as the Slumlord who profited off the Bronx’s unsafe living conditions. I did feel like this got a little bit didactic at times, but I think that’s a complaint coming from being a 32-year-old reading a YA novel and not necessarily an issue with the book itself.

Charlize, Aaron, and Raquel gear up to enter the Echo to find Cisco and bring him back, but despite their research, it’s much more than they were prepared for. To find Cisco, first they’ll have to find a way to survive at all.

This is being marketed as Stranger Things meets Jordan Peele, which I think is a fair comparison: it definitely has social thriller elements, and it has the weirdness of Stranger Things, but with a little more gore. If you want an antiracist sapphic YA social thriller and can stomach some body horror, give this one a try.

Content warnings: gore, violence, racism, gun use, police brutality, discussion of cannibalism, fire injuries/burns