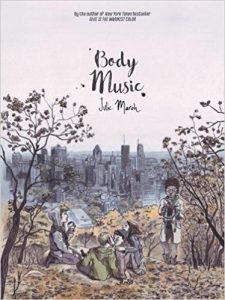

Body Music is a graphic novel translated from French, written and drawn by nonbinary lesbian artist Julie Maroh, best known for their book Blue is the Warmest Color.

It’s a series of short 5-10 page vignettes about love and desire between different people in Montreal neighborhoods. The vignettes are connected by theme and location only. The book is packed with representation–there are queer people, straight people, polyamorous people, people of color, people with disabilities, trans people, and people of all ages. The variety of the characters and situations present images of all forms of love, from healthy long-term relationships to unhealthy long-term relationships, fuck buddies to polyamory to missed connections. Sometimes sexy, sometimes happy, sometimes sad, these stories reflect that there is no singular experience of love. One person confesses their romantic feelings to their partners, a mother and a son reminisce about her dead husband, two lesbians run into a straight man with a fetish, a couple relives their first meeting at a gay bar, among others.

For a series of themed vignettes, each is unique. The writing and art style shift each chapter, enough that it doesn’t feel like there were any repeats. I feel like ‘balance’ is the keyword for this book, which uses text and image in such a way that neither feels overbearing. Moments where one fails or suffers are counteracted by an abundance of the other. Simpler stories were augmented by engaging visuals and layouts. In moments where the art didn’t have as strong a grasp on me as a reader, a poetic monologue drew me back in.

Like many collections of short stories, there are some hits and there are some misses. Sometimes the vignettes are too short to do anything other than provide a second long snapshot, which can be unsatisfying. Because there is so little context to each story, it can take a couple of pages for the reader to understand what is going on. However, these are the minority. Most stories are either engaging or poignant, and I appreciated the balance between the two.

Not every chapter has something miraculous or revealing to say, which made the chapters that did hit that much harder. One vignette about a man waiting impatiently for his partner to come back from a dinner with his ex is simply funny and entertaining. Then, two chapters later, Maroh describes the effect a terminal illness has on a relationship. It communicates both the monotony and the sacredness of our everyday lives and loves. I feel like a lot of romances or books on love tend to veer toward one or the other, so having a space where love was portrayed as both casual and revered was refreshing.

In their foreword, Maroh writes “The image of the heterosexual, monogamous, white, handsome couple, with their toothpaste smiles for all eternity, stands in the collective unconscious as the ideal portrait of love. But where are the other realities? And where is mine?” This book is incredibly important to me as a younger queer person. Mainstream media doesn’t have very nuanced depictions of both casual and serious queer love, and I haven’t gotten to a point in my life where I am having a lot of those experiences myself.

This is actually my second or third time reading this book. I first read it when I was about 17, and now, at 19, different chapters resonate with me more. When I was younger, it gave me hope for my future. Now, it’s fulfilling to recognize a few of my own varied experiences within the pages.

I tend to give away books pretty soon after I finish them, but this one has a permanent place on my shelf. It doesn’t even get loaned out. Body Music is a dynamic graphic novel with great representation and high re-read value, and it is an experience I recommend to everyone.