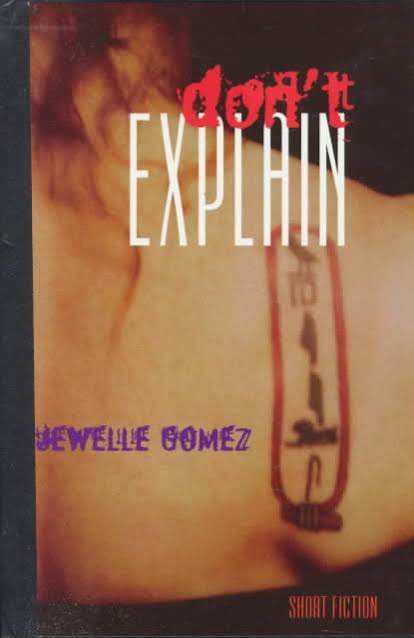

Don’t Explain is a collection of short stories by Black lesbian author, activist, and philanthropist Jewelle Gomez. Most widely known for her Black lesbian vampire novel The Gilda Stories, Gomez’s Don’t Explain is a collection of nine stories that employ rich, sensual, language to introduce readers to several carefully constructed characters whose stories set our minds and bodies afire. Although the collection was written in 1998, the stories are as poignant and relatable as they were when the book was published nearly twenty years ago.

For example, my favorite story in the collection, “Water With the Wine” is a new take on an old trope, the May-December romance. Gomez carefully deconstructs the most commonly held notions about romance between older and younger lesbians, and posits another reality for the women in her story. Alberta and Emma meet and become involved at an academic conference; however, differences in age, class and race threaten to destroy their budding relationship. Gomez deals sensitively and honestly with these issues and deepens our understanding of what it means to fall in love after the blossom of youth.

“White Flower” is a chronicle of desire, not quite erotica, but pretty close. Luisa and Naomi “can’t have a relationship, it’s too consuming too everything,” so their meetings are infrequent but filled with all of the lust and passion that two women can share. This story will leave you panting, it will also leave you wondering at what point the unbridled desire turns to obsession and manipulation.

In “Lynx and Strand,” the longest story in the collection, Gomez forays into the genre where I believe she does her best writing, speculative fiction. To put it simply, speculative fiction is not quite science fiction, not quite fantasy, but an imaginative blend of the two genres, and in this story, explores what it means to live in a future where same-sex relationships are still policed by the state. Here, Gomez tackles issues of futuristic state governments, homophobia, body art, and what it means to truly become one with your partner. The story is timely, some might say prophetic, because even though it was written nearly two decades ago, LGBTQ persons’ right to bodily autonomy is still being challenged, even threatened, in 2016.

For those familiar with Gomez’s The Gilda Stories, “Houston” offers a new chapter into the life of her Black lesbian vampire and offers a provocative look at what it means to be humane when you actually aren’t human at all.

All of the stories in this collection are sensitive, sensual, and offer a pleasant alternative to “mainstream” lesbian fiction. The collection also focuses on Black women’s experiences, and this is what truly sets it apart from most of the lesbian fiction on the market today. The collection is short, only 168 pages long, but each of the stories offers entrée into the life of Black women, mostly lesbian, that illuminates the complexity of our lives and the power of our loving. If you have not had an opportunity to read any of Jewelle Gomez’s work, start with this collection and I am certain that you will want to read more!