Tag Archives: Holly

Holly reviews Alchemiya by Katey Hawthorne

This story takes place in Chrysopoeia, a land where the art of alchemy is a celebrated craft that is known and practiced only by the higher class clans. Each clan has a particular form of alchemy that they have honed through generations to produce vibrant dyes, textiles, fragrances, gems, and metals. Our protagonist is Eugenia, a young woman born into a life of privilege as a member of the Ratna clan. Although Eugenia is very talented in her family’s particular branch of alchemy, the secrets of their alchemical history are forbidden to her because of her gender. In this patriarchal society, wealth and knowledge are passed down through the men of the family. A woman’s station in life is determined by the station of the man she is born to, and later, the man she marries.

This society strictly adheres to patriarchal power dynamics, a strict gender binary, and heterosexuality. As a woman who is driven to practice her family’s craft, Eugenia is a black sheep, but is tolerated as an oddity. However, she is ostracized by polite society when her tryst with another woman becomes a public scandal.

The standing of the Ratna clan is powerful enough that, despite Eugenia’s disgrace, they are still held in high regard. Eugenia is forced to participate in social activities at the behest of her father and brother, despite her unofficial status as a pariah. At one social gathering, Eugenia is approached by the incredibly eligible bachelor Oliver Plumtree. Oliver is the head of the one of the oldest and best-regarded families in Chrysopoeia. His interest in a person who has faced the disgrace of such a scandal shocks the community. Eugenia is flattered by the attention, and is drawn to Oliver in a way that she has never found herself drawn towards a man. We soon learn that the reason for this inexplicable attraction is…

[SPOILER]

… Oliver is actually Olivia! Oliva and Oliver were a set of twins. When the male twin (and sole heir) died as a small child, the family made the decision to raise Olivia as Oliver, ensuring that the Plumtree family’s wealth and alchemical secrets wouldn’t fall into the hands of jealous and greedy relatives. Jane Austen once said, “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” Olivia is no exception. And who better to keep Olivia’s secret than Eugenia, a woman who is vocal in her resistance to the heteronormative, patriarchal status quo?

Eugenia is thrilled by this revelation. This marriage would provide her with freedom from her domineering male relatives, the opportunity to hone her alchemical craft in earnest, and a chance to find love in a world that aims to deprive her of that possibility. Of course, it wouldn’t be much of story if there weren’t a few bumps in the road for Eugenia and Olivia to overcome. Eugenia, despite her best efforts, ends up creating trouble for herself and for Olivia, and we get to enjoy watching her try to claw her way out again.

This is a fun, fast read that, despite being easy breezy, still touches on important topics such as gender identity and intersexuality. The author knows how to spin a good yarn, and gives us a protagonist that is sometimes delightful, sometimes petulant, and sometimes both of these things at once. This is the first Katey Hawthorne book that I’ve read, but it sure as heck won’t be the last.

Holly reviews Tipping the Velvet by Sarah Waters

When I was just 30 pages in, this is the review I was considering writing for Tipping the Velvet: This book is so sweet I can barely stand it. The end. At this point I had hoped that the entire book would be a drawn out tale of Nancy and Kitty falling in love, staying in love, and laying in bed eating pie without a care in the world. Of course, Sarah Waters tells a much more interesting story.

Spoilers ahead.

Nancy, the protagonist, narrates the story. Born and raised in a small town by the sea called Whitstable, working in the family’s oyster restaurant, she lives a fairly unremarkable life until the day that she sees a male impersonator named Kitty Buttler perform at the local music hall. Nancy finds herself compelled to return to the music hall over and over, night after night, in order to watch Kitty perform. Eventually Nancy and Kitty meet and strike up a close friendship, while Nancy begins the bewildering process of falling in love.

Sarah Waters describes this process with such innocence and tenderness, and so skillfully plays on the reader’s sense of expectation, that I felt myself reacting physically to the words on the page. I clearly felt the pang in my chest, the pull at my stomach, my heart in my throat when Nancy and Kitty finally–finally!–kiss for the first time. From this giddy moment of joy to the eventual wretched heartache, we, along with Nancy, are mired in the whirlpool of doubt and certainty that accompanies the terrible and wonderful descent into the heart of another.

When reading about that heartache, I felt it, too. So, at 134 pages, my review would have been more along the lines of This book is so sad I can barely stand it. Again, Waters artfully details the nuances of emotion that accompany the anguish of heartbreak. That personal hell we’ve each experienced, in which you’re so steeped in despair that it’s all you can do to provide yourself with the necessities of life from one day to the next. I see that torment mirrored in Waters’ words. I can’t do them justice here. You have to read them for yourself.

Although the plot takes wildly unexpected turns, I feel that the characters always stay true to themselves. Nancy is vain, sometimes conniving, and seems to piece together her identity from the expectations of those around her. We do, however, see some flashes of self-actualization. For instance, when looking for new lodgings, Nancy is drawn to an advertisement for a room which reads Respectable Lady Seeks Fe-Male Lodger. She explains, “…there was something very appealing about that Fe-Male. I saw myself in it — in the hyphen.”

Waters’ descriptive ability provides specific information that allows for the reader’s senses to respond to the words on the page. The book opens with Nancy describing Whitstable oysters, and my mouth felt saturated by their description. Waters specializes in the details, creating three dimensional scenes for us to walk around in while we read her words. I didn’t realize that I had finished the book until I read the last sentence. The story was so compelling right to the end that its conclusion, although satisfying, snuck up on me.

Holly reviews Canary by Nancy Jo Cullen

In her first collection of short stories, Nancy Jo Cullen displays her talent for creating distinct characters and blessing them with the same insecurities that haunt the rest of us. Although each has their own unique personality, one commonality among all of the characters in this collection is their acquiescence to despair. From the despondent waitress/dancer to the widower whose dead wife’s ashes ride shotgun wherever he goes, it seems that each of these characters has surrendered to the oppressive hopelessness that smothers their existence. Sure, there are some glimmers of optimism here and there: The sullen teenage girl who feels invisible gets an ego boost when her older cousin rubs his hard-on against her during a consensual albeit ill-advised make-out session; A recently divorced woman achieves a sense of vindication through having all of her pubic hair waxed off and then hurling a rock through her ex-wife’s window.

However these characters identify, whoever they love (or don’t love), this book is filled with tension, desolation, and dreams that, upon being realized, don’t turn out to be so dreamy. Each of these characters aches to escape, to transcend. In “Happy Birthday”, a woman who describes her marriage to her wife as a carcass they are dragging behind them takes a night’s reprieve from motherhood and wifehood by walking out on her demented mother’s 83rd birthday party and hitchhiking to Banff. In “The 14th Week in Ordinary Time”, another tale of making-do, a closeted gay husband and a wife who would prefer to not sleep with him anyways break their celibacy in an attempt to conceive.

Situated primarily in British Columbia, many of these stories are set in the late 80’s and early 90’s, and the music of that time is often utilized to set the tone. The era’s song lyrics are woven into the narrative like musical pathetic fallacy. The stories are all sort in length, averaging about 16 pages each. They move at a good pace that keeps you anticipating what fresh socially-awkward hell these poor people will find themselves in next. The stories in this collection expose something that we can all relate to: The myriad ways in which other people disappoint us, and the futility with which we attempt to reconcile this disappointment with our innate optimism. These characters pull their terrible circumstances around their shoulders like an itchy wool blanket, and try to garner warmth despite the excruciating discomfort.

Holly reviews The Professor by Terry Castle

The Professor: A Sentimental Education collects personal essays by Terry Castle, author of The Literature of Lesbianism. Magnetic, self-flagellating, and sharp, her writing here blends personal, political, and academic thoughts on topics as diverse as teen angst and world travel. In these essays, she collects stamps, smokes pot, and talks for her slutty daschund puppy. If it sounds mundane, it is. But, part of the book’s delight is Castle’s ability to turn a plain memory into a witty and endearing reflection.

“Courage, Mon Amie,” the first essay, explores women’s interest in WWII studies. Castle discusses her curiosity about the lives of army nurses, especially the lesbian ones, and visits an ancestor and veteran’s grave site.

Continuing the theme of family, Castle contrasts her love of jazz player Art Pepper with the distance she keeps between her similarly violent but much less charismatic step-brother in “My Heroin Christmas.” She adores how butch Pepper was and hardly puts his autobiography down over the holiday. Yet, when she remembers her likewise crude step-brother launching himself off of the house banister, she does not feel remorse. She recalls her mother smiling for a split-second and cannot find it within herself to think ill of the moment. Even when he at last succeeds at killing himself, she is relieved.

“Sicily Diary” transitions to found family– to stories of her partner Blakey and their dog. This is the one piece written in diary form. Because of its structure, it quickly jumps from Italian ruins to bowel problems to jokes about the horny baby daschund. Disorienting but true to the experience of travel, the change of style works well.

The next essay, “Desperately Seeking Susan,” describes Castle’s rocky friendship with late writer Susan Sontag. Susan, too, was found family, though more distantly than the characters of “Sicily Diaries.” She was a marvel to be around but often difficult to predict and entertain, and Castle grapples with how to remember her.

“Home Alone” also deals with honoring the dead. In the wake of 9/11, Castle asks herself how she can go on with the luxurious habit of subscribing to dozens of house magazines, especially when some of her favorites completely ignore the tragedy happening just beyond their borders. Comparing interior decorating and fear, she wonders why she needs beautiful living space. The quick answer? Because her mother doesn’t.

In “Travels with My Mother,” she confesses her ongoing rebellion against her mother’s taste as she recounts their visit to the Georgia O’Keefe museum. Castle’s mother worships O’Keefe. Meanwhile, Castle is an adult hipster and also butch, neither of which her mother likes. Additionally, Castle mentions that she made the gorgeous cover for The Professor and pitches her blog, “Fevered Brain Productions, http://terry-castle-blog.blogspot.com/, which showcases her other colorful, feminist collages.

The final and title essay chronicles Castle’s grad school relationship with a female professor. She compares this to another that she has, years later, with one of her own students. All this occurs against a backdrop critique of lesbian music and a celebration of pre-Prop 8 engagement. Combined, the different elements make this essay a nuanced, strangely mournful picture of lesbian love and culture today.

Read The Professor and you will become smarter, slightly depressed, and more hip in the seventies. I highly recommend it.

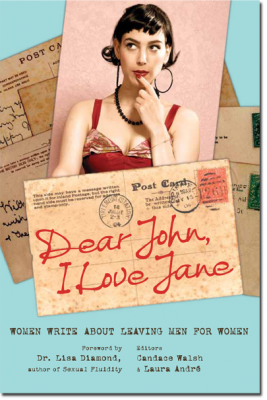

Holly reviews Dear John, I Love Jane edited by Candace Walsh and Laura André

Dear John, I Love Jane: Women Write about Leaving Men for Women, edited by Candace Walsh and Laura André and published by Seal Press, is a collection of personal essays about women who discover they’re lesbian/ bi/ queer/ otherwise in love with a woman a little later in life. For some, this means coming out to their families and friends in their middle or old age. Others learn (or change) in their twenties and thirties, which may not seem that late but can feel as though it is.

I connected with some of these stories. For instance, having to leave the country to start getting it on sounds all too familiar, writing folksy songs for one’s honey is cute, and dreaming of Angelina Jolie’s lips might just be my favorite Sapphic rite of passage.

Other narratives I found annoying. Occasionally, the dialogue seemed stilted. A couple of the first girlfriends made me want to tell the respective writers “Don’t fuck that girl. Get her a therapist.” Plus, some of the coming-out-of-the-closet-y language made me uncomfortable. There is only so much of “I didn’t want to look like a dyke”-esque sentiment that I can stand without becoming defensive.

Nevertheless, I was so grateful to be let into these women’s lives. Fluid in topic and in form, their secrets transformed into whole stories, big tell-alls that were very comforting and sexy. (Yet, it was not so lush that I wouldn’t lend it to my friends and family.) Even as a fairly young and out queer, I found Dear John, I Love Jane accessible and cathartic. This is a book I plan to keep and reread over the years. I recommend it to anyone wanting to understand the sometimes hazy pop phrase “fluid sexuality.”