Trigger Warning: This book graphic depictions of physical and sexual assault

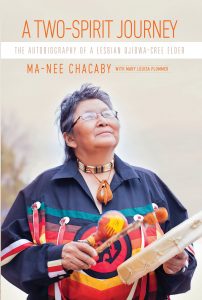

My kokum explained that two-spirit people were once loved and respected within our communities, but times had changed and they were no longer understood or valued in the same way. When I got older, she said, I would have to figure out how to live with two spirits as an adult. She warned me I probably would experience many hard times along the way. I remember her rubbing my head and shoulders, saying, ‘I feel for you. You’re not going to have an easy life when you get older.’

Chacaby, Ma-Nee (Kindle Locations 1170-1173)

Ma-Nee was born in 1950 in Thunder Bay, Ontario in a tuberculosis sanitorium. Shortly after this she was adopted by a French couple, but she was soon found by her grandmother who acquired custody and raised her in Ombabika amongst an Ojibwa and Cree community. Growing up in Ombabika, Ma-Nee learned a great deal of her heritage and traditions from her grandmother and describes many happy memories of her time her. However, at the same time, her childhood was also characterized by the physical abuse of her mother, sexual abuse from family and strangers alike, growing up in a community plagued by alcoholism, and racism from the Canadian government.

When she was a teenager, Ma-Nee was married to an older man who abused her. She experienced alcoholism herself, homophobia, visual impairment, and many more obstacles and struggles. Through her ongoing struggles, Ma-Nee persevered and found strength in herself and her community. She became a mother not only to her own children and those in her family, but to many in the foster system. She becomes an AA sponsor, an elder of her people, and a leader in the LGBTQ+ community. This is a story that outlines the racism and prejudice experienced by a Two-Spirit Lesbian Ojibwa-Cree Elder, and how she survived it all to then lead others through the same struggles.

I’ll be honest, this is a hard book to read, but an important one. The afterword describes how the book came to be, with Ma-Nee telling her story and Mary Louisa Plummer transcribing it. The end-result feels like a story that is being told you, as if Ma-Nee was in the room with you recounting her life. I found it very hard to put the book down, no matter how brutal the subject matter. The text comes alive through photographs of and paintings by Ma-Nee, giving us more of an immersive perspective into her life.

If you wish to learn more about two-spirit people, the experiences of Indigenous women, and the hardships faced by queer women of color, I highly recommend this book.