Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary!

“And keep drawing, too. Draw what you see, what happens here. It’s important. They can scare us, but they can’t make us forget.”

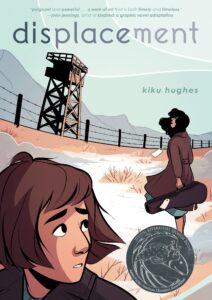

In this simply illustrated yet poignant graphic novel, Kiku Hughes reimagines herself as a teenager who is pulled back in time to witness and experience the Japanese internment camps in the U.S. during World War II. There, she not only discovers the truths of what life was like within these camps but also follows her late grandmother’s own experiences having her life turned upside down as her and her family are villainized and forcibly relocated by the American government. Kiku must live alongside her young grandmother and other Japanese American citizens, as she finds out about the atrocities they had to suffer and the civil liberties they had been denied, all while somehow cultivating community and learning to survive.

Touching on important themes of cultural history and generational trauma, Hughes meshes these topics seamlessly into a fascinating plot and an extremely endearing and relatable main character. Kiku reflects a lot, during her journey, on the way that marginalized people are treated within the U.S.—during the past and in modern time—but also on the way that her family’s history and experiences had such a great effect on her own life.

Throughout the story, she feels powerless because of the lack of information she has regarding her grandmother’s past and her community’s history, which makes it difficult to help those around her. She can’t tell them what is about to happen to them; she doesn’t know what the living conditions are like in the different internment camps they are sent to; she can’t warn them about the specific atrocities that await them. She is forced to undergo this displacement alongside everyone else, and her ignorance not only makes her scared but also makes her feel quite guilty for not being able to contribute more aid or comfort to those around her.

She is also confronted with this difficult-to-place, bittersweet feeling of being disconnected from her family’s culture but also acknowledging that her own habits and traditions have been so deeply impacted by it. All these moments of introspection felt like a personal call out to me and made Kiku the kind of main character to whom a lot of readers will be able to relate.

Because of my own relationship to my family’s culture and history, reading this graphic novel was an extremely personal and emotional experience. On one hand, I think a lot of people will be able to connect with this story; on the other hand, I think a lot of other people will have the opportunity to learn something new through it.

I also loved the subtle sapphic romance arc that was included. It didn’t overpower the main message of the novel, but it was a nice, comforting surprise in an otherwise heavy read. I saw it as a beautiful testament to the joy and love we humans are capable of finding, even in moments of great duress.

The illustrations were beautiful, the art style was simple but extremely effective, the characters felt very fleshed out—which is sometimes hard to do in a graphic novel, working within a limited number of panels. All the artistic choices perfectly matched the tone of the story, which is a testament to Hughes’ true talent as a creator.

Representation: sapphic, Japanese American main character

Content warnings: racism, racial slurs, colourism, sexism, hate crimes, cancer, death, grief depiction, confinement, imprisonment, war themes (World War II and Japanese internment camps)