As you may recall, Cass from Bonjour, Cass challenged me to read The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall, that old depressing lesbian classic. I accepted the challenge. What we also did, though, is discuss/rant about the book together. We had two conversations about it. I’ll be posting excerpts of the first one (when I didn’t have notes) and Cass will be excerpting from the second one (when I did have notes and we were both a little more organized). Here are the highlights, with spoilers marked. I’m sorry to say that we started at the end, so the beginning is a little spoiler heavy. Spoilers are up for interpretation, though, so I hid plot points but showed who the major romantic lead is and general things like that.

Danika: […] Okay, so, to get started… overall impressions? I liked Stephen as a character right up until the end, where she started doing stupid, manipulative, controlling things. I thought she was really sympathetic until maybe the last tenth of the book, when I lost a huge amount of respect for her.

Cass: Stephen’s a bit of a jerk. [highlight to read spoilers] Who’s she to decide Mary wants to marry a man even Stephen didn’t want to marry? I appreciate Hall’s argument for tolerance and acknowledgement (“Give us also the right to our existance!”), but the ending is frustratingly …something. Paternalistic, maybe. [end of spoilers]

[…]

D: That’s exactly what I thought! In the end, I realized that Stephen is pretty sexist. She had that whole “I know what’s best for you better than you do” attitude. I wasn’t impressed. [spoilers] But what’s-his-name (see, this is why I took notes), the romantic competition, was just as bad. I was furious at both of them.

C: Martin! Martin is a big dumb jerk, too.

D: Ah, yes, Martin. I looooved Martin when he first came on the scene. (I live in BC, so I was like “Yes! Trees!”) Then, like Stephen, he took this nose dive as a character in the end. Sigh.

C: Stephen’s whole “Mary would be so much happier with a man” plan (without, you know, consulting Mary) [end of spoilers] really examplifies the problem with the Inversion theory.

D: Inversion theory?

C: Inversion as opposed to lesbianism. Like, an invert is a masculine woman or a feminine man. And they are doomed to forever fall in love with people they can never be with. Since of course they can’t be with one another.

D: Oh, yes. That really is pushed in WoL, huh? Because Mary is feminine and (by our current labels) bisexual, or even straight-with-an-exception, because you can’t be exclusively attracted to women if you’re feminine.

C: Oh, I don’t know about that. I think we put Mary in a lesbian bar circa-1955, she’d be all over the butches.

D: Probably. But I think that’s how Stephen sees her. I guess I think Stephen doesn’t really know her all that well at all, or at least doesn’t respect her. Because I think Stephen thought that without her influence, Mary would be “normal”.

C: Yes. Oh, inversion. How I shake my fist at you.

D: Definitely. So, again coming at it with 2010 labels, do you think WoL first more under a trans umbrella or a lesbian one? I think they can be read from both perspectives, but do you think it fits more into one than the other?

C: I really don’t think it’s fair to push our labels onto a book from 1928. Trans- identities are, by definition, personal and self-definied/understood, that I think it’s impossible to decide whether or not Stephen Gordon is a trans character. We’d have to ask her. But if I had to make a decision, I’d say it’s a lesbian novel. And even though I’d love to, I’ll still resist calling Stephen a butch, for the same reasons. But I know you think of it as more of a trans novel. Care to rebut?

D: A very good point. Not that Stephen would be able to tell us, because she didn’t have the language. It’s odd, though, because the first half of the novel I was very, very sure that Stephen’s gender was more of an issue for her than her sexuality. I mean, by… what was it, 7 or 9? Something like that. As a kid, at least, she got a crush on a woman, so her sexuality did come up early, but her gender seemed to be an issue even earlier. I mean, even before she was born her parents were sure she was a son (not that that was unusual for the time). She was named Stephen. She hated anything feminine, any feminine clothing, her long hair, etc. She spent a long period in her childhood dressing up like a boy. There’s a great quote somewhere (I have it in my notes) where she asks her father if she could be a boy/man if she really tried hard, or if she prayed hard enough. She looks exactly like her father. I mean, it’s hard to tell if she really is “butch” (again, I know it’s silly to apply 2010 labels to 1928, but for the sake of argument) rather than trans. And, who wouldn’t want to be a man in 1928? It was a better life. So I’m divided, but I think there’s a good argument for it being a trans novel.

After she cuts off her hair and buys her own clothes, though, those issues seem to fade to the background and her sexuality becomes the big issue. There is one passage where she looks in the mirror and hates her body, but hating your body is a genderless problem, so again, hard to say.

[…]

C: The term ‘homosexuality,’ while in use in 1928, didn’t yet have its modern definition or its now understood division from gender. Inversion, on the other hand, completly tied sexual orientation to one’s gender and gender expression. A person labelled female at birth could not, by defition, be an invert without displaying masculine traits and masculine leanings. Therefore, in order to be a novel ABOUT inversion, Stephen has to be masculine. If we are using our modern lens here, then we can agree that, despite her masculinity, Stephen is not automatically male. The fact that her parents gave her a traditionally male name is out of her control. Lots of girls who continue to identify as women like to dress in pants rather than dresses because they are easier to walk and play in. Looking “like a man” or being masculine doesn’t make a person a man.

The conversation with her father is trickier, but if she has a crush on a girl, and thinks that only men and women can have relationships together, it’s logical that she would want to be a man in order to be happily in love with a woman.

D: True, but coming from a modern perspective, that assumes that you are by default the gender you were assigned at birth and only the opposite if there is overwhelming evidence. We don’t have overwhelming evidence that Stephen would identify as a man, but we have a lot less evidence than there is for Stephen identifying as a woman. She can’t stand to even be around women, except the ones she falls in love with.

That makes sense, but it isn’t just around having a partner that Stephen is frustrated at being labelled a girl. In fact, as some point she said “Being a girl ruins everything” (not an exact quote)

C: […] [H]er gender and gender expression can be on the trans-masculine spectrum without her necessarily being trans. In 1928(ish), being a girl DID ruin everything!

I think you are the gender you understand yourself to be, but sadly I can’t ask Stephen. 😉

D: Oh, and I meant to say in that first paragraph that of course she doesn’t hypothetically have to identify with either or just one. If I’m assigning modern labels, Stephen is probably more butch or genderqueer than transman, but you’re right in that it’s so very much a personal definition that it’s pointless to guess at that.

[…] I definitely think think Stephen would be in the trans-masculine spectrum, but isn’t that under the trans umbrella? Of course, it depends on how wide we’re making the umbrella, because under a lot of definitions Stephen would be included there by default because of her refusal to conform to gender norms in dress, hair, attitude, etc.

That’s a big part of the problem in trying to assess Stephen’s discomfort with her gender. Is it because she feels more trans, or is it just a natural reaction to the restrictive nature of being a woman at the time?

[…]

D: Okay, did you notice that animals can practically talk in WoL?

C: Why do animals always die in gay books? Why? And what is with LESBIANS and HORSES. Excuse me. INVERTS. Inverts and horses.

[…]

D: I thought that one of the ongoing themes in WoL is that aging is a tragedy. Everybody gets old and it is terrible.

[…]

C: Do you think TWOL is still important reading?

Hall hates the feminine ladies. Poor Mary. Do you think Lady Una gave Hall a good talking to after she read TWOL?

D: Yeah, I got definitely get a whiff of misogyny from WoL.

I think so. I mean, like I was saying in my post, it’s amazing/depressing the things that are still relevant. Stephen actually makes a pretty good case for same sex marriage, letting queer people serve in the army, and letting gay people adopt. It’s a sympathetic plea, partly because Stephen is so traditional other than her “inversion”.

I hope so. I wonder what Hall’s other books are like, if they all have this feminine = weak theme

C: I will be honest. I just hate BEING GAY IS SO HARD books. I know it CAN be hard and there are problems, but these books make it sound like we’re the most miserable bunch ever.

D: Ugh, I know. And the unhappily ever after queer books. When you’re already dealing with a tough time coming out or something, you don’t want to read about “DON’T BE GAY OR YOU’LL DIE/GO INSANE”. Of course, being gay in 1928 would be pretty awful.

C: Granted, 1928, not such a good year for the ole inverts.

[…]

C: What’s your favorite happy ending lesbian book?

Rules: 1) No one can die. 2) No horses 3) No rape.

Okay, commence. […] ( I can’t think of any.) […] Are you stumped because I am stumped.

[…]

D: THOUGH, and this is one of my issues in the book, Stephen could have had it so easy! You’re freaking rich, Stephen! You can lavishly support your hot young girlfriend! You can go on vacations and hold big lesbian parties! Why so sad?

And that was about it for our first conversation! I cut out the slightly off-topic meanderings (talking about the WoL covers, other lesbian books covers, and some other lesbian books), but if anyone’s interested in reading our random babbling, I can post that, too.

Check out more of Cass and I talking and complaining (I kid, I like it despite some of its issues) at Bonjour, Cass!

And hey, if anyone wants to do something like this with me again, just let me know! I’d probably be up for it. You don’t even need to be a book blogger. In fact, feel free to email me about lesbian books anytime (my email is in the About Me) section. It is my favourite topic! You can also ask me questions (even anonymously) on my Formspring.

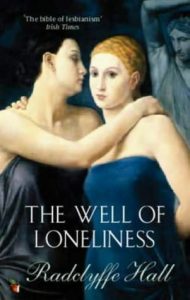

Do not let this be the first lesbian book you read! If I was doing this list by order of which is most classic, I would start with this one, but it violated my cardinal rule: don’t be depressing. I recommend Well of Loneliness because it’s a classic (published in 1928), because it was actually surprisingly not very difficult to read, and because it was judged as obscene although the hot lesbian love scene consisted entirely of “And that night they were not divided”, but it’s not a pick-me-up book. In fact, if it wasn’t such a classic, I never would have read it at all; I refuse to read books that punish characters for being queer. I also got the suspicion while reading it that the protagonist was transgender, not a lesbian. Lesbian (or transgender?) author.

Do not let this be the first lesbian book you read! If I was doing this list by order of which is most classic, I would start with this one, but it violated my cardinal rule: don’t be depressing. I recommend Well of Loneliness because it’s a classic (published in 1928), because it was actually surprisingly not very difficult to read, and because it was judged as obscene although the hot lesbian love scene consisted entirely of “And that night they were not divided”, but it’s not a pick-me-up book. In fact, if it wasn’t such a classic, I never would have read it at all; I refuse to read books that punish characters for being queer. I also got the suspicion while reading it that the protagonist was transgender, not a lesbian. Lesbian (or transgender?) author. 1)

1)