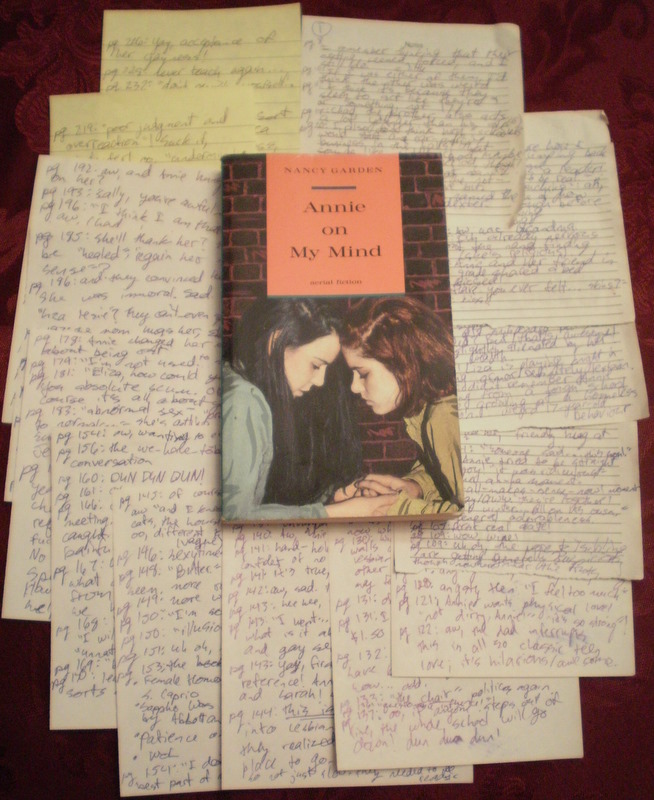

Nancy Garden, author of the classic Annie on my Mind, wrote another poignant novel about lesbians. This time, she touched on controversy about homosexuality, censorship, and free speech. The Year They Burned The Books is that novel.

Published in 1999, this story still rings true today about how far censorship and prejudice can go. The story revolves around Jamie Crawford, a senior at Wilson High School, who is editor of the school paper, the Telegraph. She is coming out to herself as a lesbian. In her school, a new policy comes out, allowing condoms to be distributed in the nurse’s office. When Jamie writes an editorial supporting it, she is met with opposition, especially from Lisa Buel, a woman running for a position on the school board. Lisa wants to rewrite the entire school curriculum, including removing books on homosexuality, discussing abstinence, and omitting facts about cohabiting couples. When Jamie stays true to her views, other students begin to lash out at her, and the school paper. Soon, Jamie’s town comes under a huge censorship scandal, and she and her gay friends face discrimination.

The Year They Burned The Books nails it when it comes to discrimination and free speech rights. Nancy Garden based this book off a real-life event, when copies of her novel Annie were burned on courthouse steps in a town in Kansas, and the books were nearly banned from schools in the district. The Year They Burned The Books shows accurately how far discrimination can be taken.

The main conflict in the story starts out with the health curriculum, but as the novel progresses, the characters begin to spar over things like religion and homosexuality. Jamie is firm in her opinions, but there are a couple characters who are conflicted. Nomi, Jamie’s longtime friend, wants to stay Jamie’s friend, but the church she goes to says homosexuality is immoral. She must wrestle with her beliefs and come to her own conclusions. Then there is Ernie, the boyfriend of Terry, Jamie’s best friend. Ernie loves Terry, but his parents are completely against homosexuality. He feels he has to be straight, and feels loathing and disgust towards himself. He too must try and reconcile his beliefs with his sexuality.

Other characters were highly unlikeable, especially Lisa Buel. She promotes discrimination in the name of her religion, and her insults towards homosexuals are infuriating. As she campaigns for school board membership, she purposely deceives voters by not sharing her true intentions. She also resorts to extreme measures, one being checking out library books about gays and lesbians, burning them, and then lying about burning library books. These things showed her bad side.

This story can be heavy at times, with Jamie and her friends getting scary notes in school, the town’s narrow-minded side, and the school paper coming under fire because of Jamie’s editorial. Many students at Wilson High go to church one day, and the next day they launch hatred against the gay students. Nancy Garden wasn’t afraid to show this side of people, which I applaud.

I also loved how Jamie and her friends stuck with their beliefs and stood up to those who hated them. One of my favorites was Tessa, the new girl at school. She was dead firm in her human rights opinions and was not afraid to say so. She and Jamie made perfect friends, and balanced each other out. Terry was also not afraid to jump in to defend those he cared about, especially Ernie.

The Year They Burned The Books had its tense moments, and times when I got really angry. But there was still goodness and hope in the story. It was a satisfying read, and gays and lesbians should read this. Straight people should read it too, as it touches on all true subjects and challenges censoring people’s opinions. Some may disagree with the views expressed in this book, but that’s okay, as long as everyone can believe what they want without being hurt. That’s what this novel teaches; being entitled to your beliefs without being persecuted. I thought this story was amazingly told, and with a sympathetic, likeable heroine, The Year They Burned The Books should be a major classic as well.

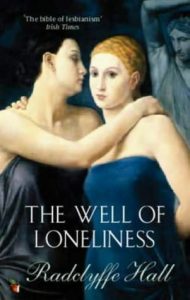

Do not let this be the first lesbian book you read! If I was doing this list by order of which is most classic, I would start with this one, but it violated my cardinal rule: don’t be depressing. I recommend Well of Loneliness because it’s a classic (published in 1928), because it was actually surprisingly not very difficult to read, and because it was judged as obscene although the hot lesbian love scene consisted entirely of “And that night they were not divided”, but it’s not a pick-me-up book. In fact, if it wasn’t such a classic, I never would have read it at all; I refuse to read books that punish characters for being queer. I also got the suspicion while reading it that the protagonist was transgender, not a lesbian. Lesbian (or transgender?) author.

Do not let this be the first lesbian book you read! If I was doing this list by order of which is most classic, I would start with this one, but it violated my cardinal rule: don’t be depressing. I recommend Well of Loneliness because it’s a classic (published in 1928), because it was actually surprisingly not very difficult to read, and because it was judged as obscene although the hot lesbian love scene consisted entirely of “And that night they were not divided”, but it’s not a pick-me-up book. In fact, if it wasn’t such a classic, I never would have read it at all; I refuse to read books that punish characters for being queer. I also got the suspicion while reading it that the protagonist was transgender, not a lesbian. Lesbian (or transgender?) author. 1)

1)