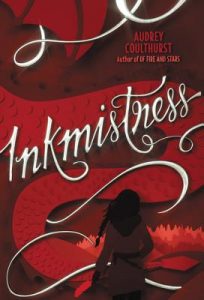

Inkmistress is Audrey Coulthurst’s second novel, and the first of her works that I have personally read. It’s the story of a young demigod hermit, daughter of a human and a wind god, whose teacher has raised her separate from human beings in an effort to protect her from them. Asra is an herbalist who has the power to write fate into being by using her blood as ink and her lifespan as fuel. She’s used the power only once before, inadvertently causing an ecological disaster, so it’s only out of the real fear of losing something precious to her that she uses it for a second time. The love of her young adulthood, a human villager named Ina, is sworn a political marriage with the ruling son of another village unless unless she can gather enough of her own power to not need to marry. In this world where every human being takes on a “manifest,” a bond with an animal which allows them to shapeshift, Ina’s lateness to develop the skill has made her vulnerable. Longing to marry her herself, Asra writes Ina will find her manifest tomorrow, and her lack of specificity sets off a chain reaction of horrors; the village is massacred by invading bandits, and Ina takes a dragon as manifest by force, cutting herself off from the gods and dedicating herself to vengeance. Asra has no choice but to follow her, down from the mountains she has lived in all her life, desperate to turn Ina from her horrible quest.

This book had me walking a balance beam between “Oh, I really like that!” and “Hmm, I think I would have done that differently,” which means it kept my attention until the last page. I liked that the magic got very little explanation, and that was explained wasn’t done in a way that kicked me out of the narrative. I very much enjoyed that the appearances of characters were described naturally, with no resorting to weird food metaphors to describe the characters of color. I appreciated that there was a sense of history to the piece, without any of the plodding common to early works of fantasy novelists; the characters were simply living their lives, navigating what eddies they had to to keep from drowning in fate, and the fact that they were in a world where the gods were very close to them didn’t matter as much as getting the harvests in, or avoiding a well-traveled road on a muddy day.

Both the protagonist and the antagonist of Inkmistress are bisexual, each of them having partners of multiple genders within the text, and it goes unremarked-upon by other characters, which is something I found comforting. In a world with dragons and shapeshifting warrior kings a person’s sexuality should be a subject of no note. That said, there is a character who was disowned by her parents for getting pregnant without getting married first, so this world isn’t that far divorced from our own, which made the world feel familiar.

The things that I didn’t enjoy as much mainly came down to characterization. Asra has spent her entire life on a mountaintop, separate from the village below and, after her master dies, totally alone for all the winter months. This has instilled in her a certain believable naivety and hunger for human communication, and it doesn’t seem like she ever overcomes that during the course of the novel. No matter how she is abused or manipulated for it, she does not gain worldliness. In addition, despite the fact that she’s had it drilled into her head since infancy that her powers are dangerous, and that humans will take advantage of her to force her to use them, I’m not sure there’s a character with a speaking role who she doesn’t end up blabbing her secret to. Predictably, this leads to her becoming a weapon for one character after another to use against their enemies. This does drive the plot, but I kept wondering how Asra thought she was going to survive, when everyone who knows her name seems to know that her blood could make them into something approaching demigods themselves.

I was most of the way through the book before I realized what it was reminding me of: there was a ghost of the same sort of driven desperation that I enjoyed in N.K. Jemisin’s “The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms.” That was a good surprise, since I adored that novel, and I could see something of a quieter, less-driven Yeine in Asra. Asra accepted that she had only so much power, and due to that, that her agency was limited. She never had enough choices, and none of the ones in front of her were good; in defter hands, that could have taken on a beautiful anxiety. As it is, the character’s constant uncertainty made her come off to me as a bit weak-willed.

Weak-willed can be kind of interesting, though, and Asra’s malleability was consistent. While she couldn’t adhere to one frame of mind or one decision beyond “Stop Ina,” she’s that rare protagonist who is both terrible at saying no, to anyone, and generally capable of getting her own way out of her problems. The fact that “out of a problem” means “into a worse problem” every single time just ratchets up the tension.

That said, I thought that the last few pages were a bit too pat and easy. Asra had gone through physical, spiritual and emotional agony to come to where she was, but throughout the entire narrative she wasn’t ever able to make a choice and stick to it. She vacillated between supporting one villain or another, walking one path or another. Wind’s daughter that she’d thought herself to be, wind’s lover that she becomes, it seemed as if she spent the entire novel being blown this way and that, with little control of her direction. I would have liked to see her plant her feet and make real demands of the world around her.

Final rating: ***

Genevra Littlejohn is a multiethnic, queer martial artist who lives in the woods with her partner and their two cats, baking and reading and cussing at her tomato garden. She’s at http://fox-bright.tumblr.com, or you can find her on Facebook.

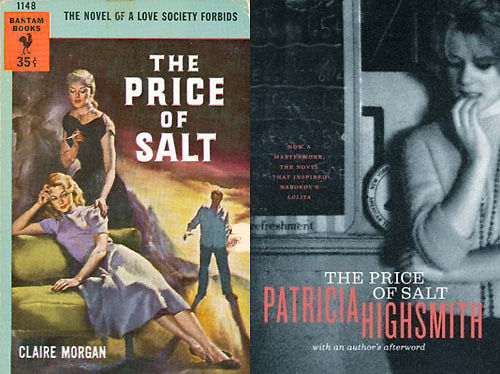

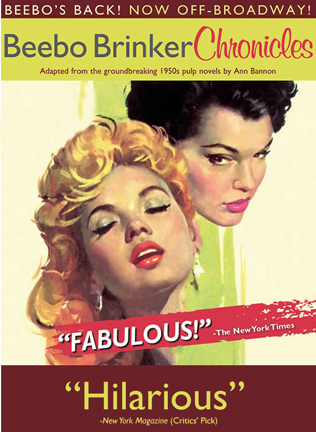

Anna: As a starter question, I’d be interested to know what you thought about the way Bannon portrays her character’s discovery of her same-sex desires (especially the way it is mediated to some extent by her mentor/roommate). It was an interesting contrast to the way the girls in our YA novels came to terms with their sexual orientation — primarily through their interaction with other girls and their own internal self-reflections.

Anna: As a starter question, I’d be interested to know what you thought about the way Bannon portrays her character’s discovery of her same-sex desires (especially the way it is mediated to some extent by her mentor/roommate). It was an interesting contrast to the way the girls in our YA novels came to terms with their sexual orientation — primarily through their interaction with other girls and their own internal self-reflections.  gender/sexual identity versus appearance. For Beebo, her appearance determined and shaped her gender and sexual identity, whereas now we think of people are expressing their gender/sexual identity through their appearance. I say gender and sexual identity because there are many ways to be read as lesbian (or gay or queer) through appearance: shaving one side of your head, or having short hair, or wearing rainbow accessories, etc. Gender expression through appearance is pretty obvious.

gender/sexual identity versus appearance. For Beebo, her appearance determined and shaped her gender and sexual identity, whereas now we think of people are expressing their gender/sexual identity through their appearance. I say gender and sexual identity because there are many ways to be read as lesbian (or gay or queer) through appearance: shaving one side of your head, or having short hair, or wearing rainbow accessories, etc. Gender expression through appearance is pretty obvious. Anna: “I would hypothesize that the sex scenes in pulp are probably the easiest way to see whether the book was written by a Real Live Lesbian who has actually had sex with another women rather than a straight man who’s just imagining it.”

Anna: “I would hypothesize that the sex scenes in pulp are probably the easiest way to see whether the book was written by a Real Live Lesbian who has actually had sex with another women rather than a straight man who’s just imagining it.”