Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! “I no longer wish to be called resilient. Call me reckless, impatient, and emotional. Even Indigenous. Call my anything other than survivor. I am so many more things than brave.” One of my favourite books I’ve read this year is Thunder Song, LaPointe’s newestRead More

A New Classic of Queer Memoir: Hijab Butch Blues by Lamya H

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! I have had Hijab Butch Blues by Lamya H on my list since it came out, and I am so glad my library hold on it finally came in. Lamya narrates a series of essays tying together her queer coming of age and herRead More

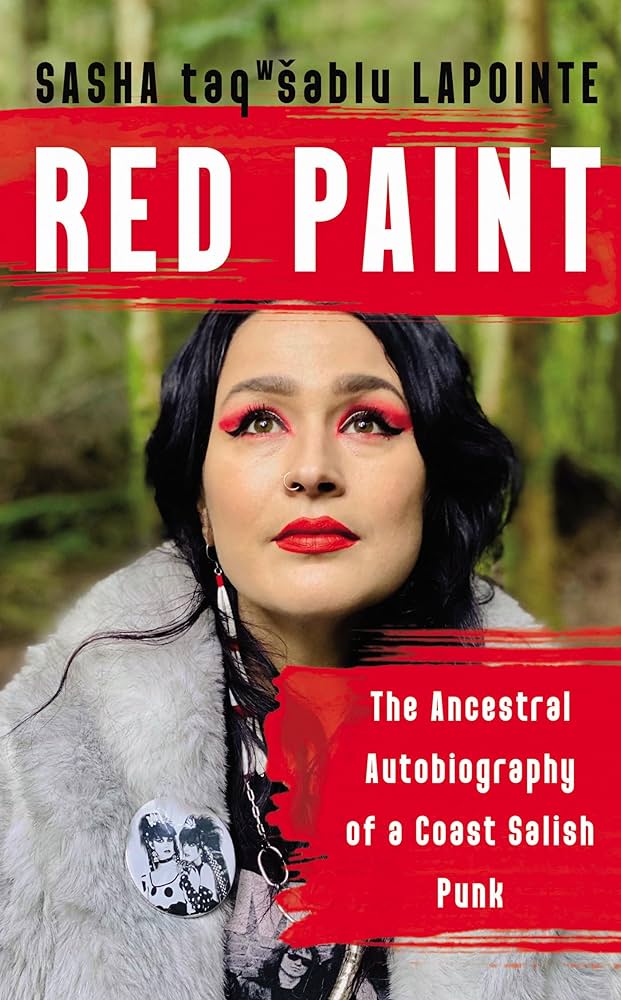

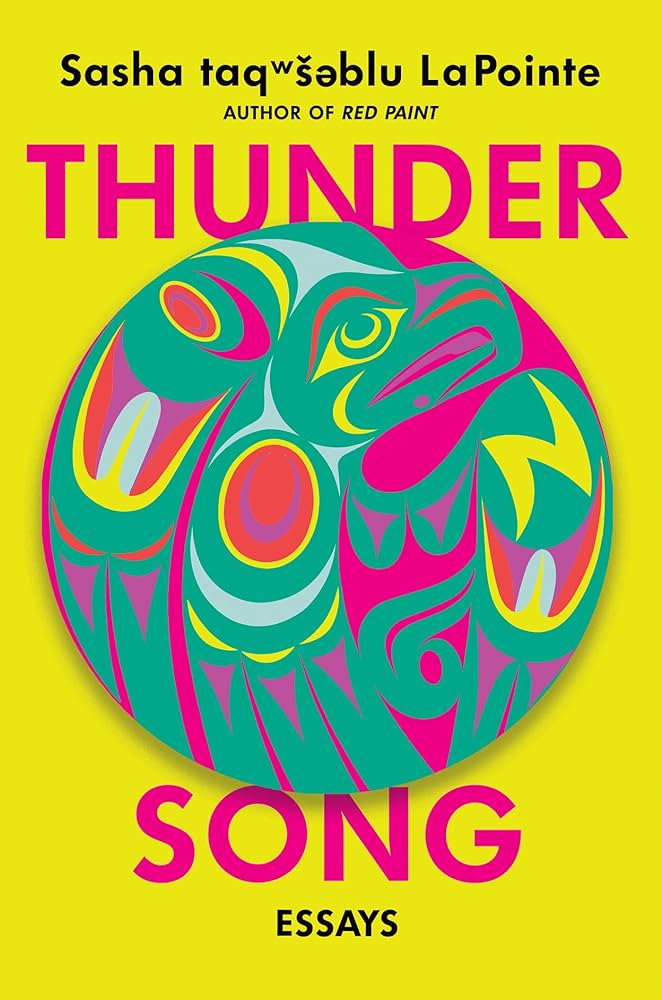

The Song the World Needs: Thunder Song by Sasha taqwšəblu LaPointe

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! This was one of my five star predictions for the year, and I’m happy to say it lived up to that expectation. Thunder Song is a collection of essays about being a queer Indigenous women in the U.S. today. It begins with LaPointe talkingRead More

A Dazzling Debut: How Far the Light Reaches by Sabrina Imbler

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! I first learned about Sabrina Imbler (they/them) last year when my girlfriend and I traveled to Seattle to watch the UConn Women’s Basketball team compete in the Sweet 16. Whenever I travel, I like to visit a local bookstore, which is how we endedRead More

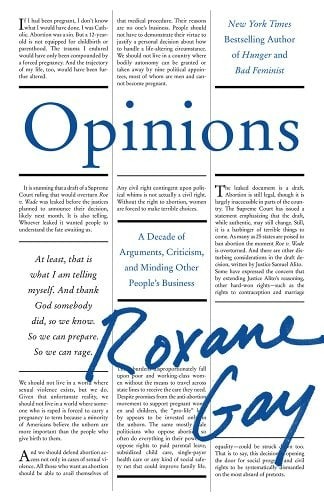

The Audacity of a Point of View: Opinions by Roxane Gay

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! In Opinions: A Decade of Arguments, Criticism, and Minding Other People’s Business, Roxane Gay (she/her), author of New York Times bestsellers Bad Feminist and Hunger, delivers an expertly curated collection of her opinion writing on a host of different topics from approximately 2013 toRead More

What is “Queer Enough?”: Greedy: Notes from a Bisexual Who Wants Too Much by Jen Winston

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link In their book of essays, Jen Winston (she/they) covers various topics about her bisexual experience, from the adoption of random behaviors as “bisexual culture” out of a desperation to be seen to the grief of friendships evolving when your best friend becomes a “we.” Winston talks through internalizedRead More

Danika reviews How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures by Sabrina Imbler

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link This may be my favourite book I’ve read this year, and there’s been some stiff competition. How Far the Light Reaches is exactly what the subtitle promises: a life in ten sea creatures. It weaves together facts about aquatic animals with related stories from the author’s own life.Read More

Rachel reviews Girls Can Kiss Now: Essays by Jill Gutowitz

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Hilarious, poignant, and stunningly clever, Jill Gutowitz’s essay collection Girls Can Kiss Now was one of my most anticipated reads of 2022 and it definitely did not disappoint! When I talk about this book (which is often), it usually goes something like this: “I’m reading this book, it’s called Girls CanRead More

Kayla Bell reviews Love is an Ex-Country by Randa Jarrar

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Love is an Ex-Country is part memoir, part essay collection. It touches on a variety of topics, from racism to queerness to fatphobia to Arab identity, while always keeping an engaging, almost playful tone. There are many reasons why it worked for me so well. Before I getRead More

Sinclair reviews Untamed by Glennon Doyle

I was skeptical about this book. Remember back in May 2020 when nearly the entire bestseller list was taken up by anti-racist titles such as How To Be An Anti-Racist, Me & White Supremacy, and My Grandmother’s Hands? Untamed was also on there, and I felt skeptical about a white woman’s voice being amplified so loudly during such aRead More