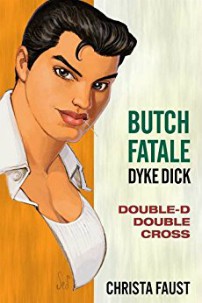

Butch is the quintessential hand-to-mouth PI in LA. Her first client in a while is a butch lesbian like herself who hires her to find out why her girlfriend has left her and gone back into the prostitution trade. Murders ensue and characters are introduced, described, questioned, and usually fucked until Butch finds herself pointed in the right direction to solve the case.

Faust, who seems to have done it all, is a professional writer who rarely makes mistakes. She has a curiously masculine style of writing. Either that or she is successful in masculinizing Butch’s first-person point of view without in any way making her seem like a man. The mystery is a good one, going from one clue to another logically and building up suspense along the way.

Despite these good things, I can’t shake the idea that Faust wrote the novel primarily because she came up with the name Butch Fatale. The fact that—unlike most of her other books—Butch Fatale is available as an e-book only (despite the fact that releasing it as a paperback would cost her virtually nothing) makes me think that Faust is tossing the book off as something insignificant. Or as a kind of joke. More disturbing still is the possibility that she intended it as a parody of a hard-boiled detective novel using a butch lesbian as the detective to give it more humor.

This is unfortunate because Butch is a winning and likeable character. In fact, she’s someone I wouldn’t mind hanging out with as long as bullets weren’t flying around our heads the whole time. The novel could have been a top-notch lesbian mystery and probably one of the best of these featuring a PI. Trouble is, we never really know whether the book is meant to be in any way serious. Maybe I’m not the best person so judge this because I have notoriously little sense of humor but this book goes from a nail biter to a Keystone Cops routine at the drop of a hat. In the climactic last scene, Faust goes completely over the top, creating a chase scene that would probably have a TV audience chuckling, but leaving this serious reader scratching her head.

Another problem is that Faust seems obsessed with showing Butch having sex with virtually everyone she meets except her secretary (see Mannix, James Bond, Cormoran Strike, etc.), who is really the only one who loves her. This randiness would almost pass muster, at least for the first half of the book, but when she continues to undress woman after woman—even under threat of death, even after she takes a bullet—it gets old and occupies too much of the narrative. Is this overuse of sex a spoof of something? Maybe, but there are very few lesbian mystery characters who act in a similar manner.

I suspect—and this is of course my opinion only—Faust decided to make Butch Fatale a humorous , almost ridiculous Phillip Marlowe instead of a PI that would stand tall in the pantheon of lesbian literature. Either that, or she changed her mind about what the book was supposed to be a couple of times as she was writing it. There is a great danger that some readers will consider Butch to be the butt of a novel-long joke, which is disrespectful to both the character and to lesbian mysteries in general. Humor is fine, but not ridicule. Too bad. Give it a 3 for the professional writing and hope that a second novel in the series gives Butch the respect she deserves and maybe a little more backstory. I will be waiting, and at a reasonable price, I will be a willing reader.

For over 250 other Lesbian Mystery reviews by Megan Casey, see her website at http://sites.google.com/site/theartofthelesbianmysterynovel/ or join her Goodreads Lesbian Mystery group at http://www.goodreads.com/group/show/116660-lesbian-mysteries

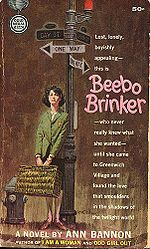

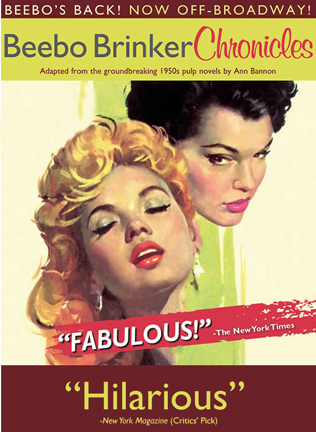

Anna: As a starter question, I’d be interested to know what you thought about the way Bannon portrays her character’s discovery of her same-sex desires (especially the way it is mediated to some extent by her mentor/roommate). It was an interesting contrast to the way the girls in our YA novels came to terms with their sexual orientation — primarily through their interaction with other girls and their own internal self-reflections.

Anna: As a starter question, I’d be interested to know what you thought about the way Bannon portrays her character’s discovery of her same-sex desires (especially the way it is mediated to some extent by her mentor/roommate). It was an interesting contrast to the way the girls in our YA novels came to terms with their sexual orientation — primarily through their interaction with other girls and their own internal self-reflections.  gender/sexual identity versus appearance. For Beebo, her appearance determined and shaped her gender and sexual identity, whereas now we think of people are expressing their gender/sexual identity through their appearance. I say gender and sexual identity because there are many ways to be read as lesbian (or gay or queer) through appearance: shaving one side of your head, or having short hair, or wearing rainbow accessories, etc. Gender expression through appearance is pretty obvious.

gender/sexual identity versus appearance. For Beebo, her appearance determined and shaped her gender and sexual identity, whereas now we think of people are expressing their gender/sexual identity through their appearance. I say gender and sexual identity because there are many ways to be read as lesbian (or gay or queer) through appearance: shaving one side of your head, or having short hair, or wearing rainbow accessories, etc. Gender expression through appearance is pretty obvious. Anna: “I would hypothesize that the sex scenes in pulp are probably the easiest way to see whether the book was written by a Real Live Lesbian who has actually had sex with another women rather than a straight man who’s just imagining it.”

Anna: “I would hypothesize that the sex scenes in pulp are probably the easiest way to see whether the book was written by a Real Live Lesbian who has actually had sex with another women rather than a straight man who’s just imagining it.”