“Dark Academia” is a cultural trend sweeping Tumblr and Tiktok, an eclectic sub-community gauzed in stark, academic aesthetic and darkly gothic themes. On any dark academia moodboard, you can find androgynous tweed suits, dark libraries, sepia-tined cigarette smoke. However, the trend has little place for female characters or sapphic relationships, as it primarily focuses onRead More

Meagan Kimberly reviews You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Zaina Arafat’s You Exist Too Much follows an unnamed narrator as she struggles with her love addiction. The protagonist moves from one toxic relationship to another, and when she finds something that could be solid, she self-sabotages. Told through a series of vignettes, the novel spins the taleRead More

Meagan Kimberly reviews Not Your Sidekick by CB Lee

Jess Tran comes from superhero parents and has an older sister with powers, but she did not inherit this gene. She decides to find her own way in a world of metahumans and superpowers and ends up at an internship working for The Mischiefs, her parents’ and the city of Andover’s nemeses. However, everything isRead More

Meagan Kimberly reviews If You Could Be Mine by Sara Farizan

Childhood friends Sahar and Nasreen are desperately in love, but living in Tehran, their love is forbidden. Nasreen wants to lead the life her parents want for her, to marry a good man with a good job who can take care of her, even if it means she has to give up her childhood sweetheart.Read More

Kayla Bell reviews The Labyrinth’s Archivist by Day Al-Mohamed

Are you looking for a book with a diverse cast, compelling story, great worldbuilding, and disability representation? Lucky you, because you have The Labyrinth’s Archivist. This fantastical novella stars Azulea, the newest in a long line of Archivists, the people who interview travelers and make maps of the worlds that extend out from the Archivists’Read More

Danika reviews Kenzie Kickstarts a Team (The Derby Daredevils #1) by Kit Rosewater, illustrated by Sophie Escabasse

The Derby Daredevils is a middle grade series following a junior roller derby team, with an #ownvoices queer main character. Now, if you’re like me, you’ve already clicked away to order a copy or request it from your library. And that would be the correct response. I am jubilated that we are finally at theRead More

Danika reviews Bury the Lede written by Gaby Dunn and illustrated by Clare Roe & Miquel Muerto

This is the third book I’ve read by Gaby Dunn, all back to back (to back). There are some similarities: I Hate Everyone But You and Please Send Help… also have a bisexual intern reporter whose moral compass may be a little bit off. But while the novels have an unshakable friendship at their core, whichRead More

Tierney reviews The Necessary Hunger by Nina Revoyr

Published in 1997, The Necessary Hunger is one of those novels that should be on the required reading list for queer women: it so perfectly depicts its protagonist’s emotional journey, impeccably capturing the essence of adolescent passion, basketball, unrequited love, and this particular moment in time in 1980s Los Angeles. The novel is told from Nancy’s pointRead More

Joint review: Beebo Brinker by Ann Bannon

If you haven’t read one of my joint review posts, this is how it goes: me and another blogger both read pick a lesbian book to read at the same time, then we discuss it, either through instant messages or by email. Anna from the feminist librarian read Beebo Brinker by Ann Bannon with me,Read More

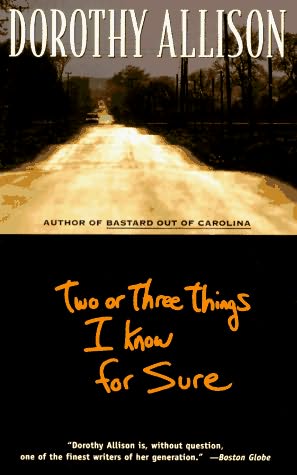

Danika reviews Two or Three Things I Know for Sure by Dorothy Allison

I love this book. Love, love, love. If you’re a lesbian book fan, and I’d be pretty surprised if you’re reading this and aren’t, you’ve probably heard of Dorothy Allison’s lesbian classic Bastard Out of Carolina. I haven’t read that one yet, but I’ve been wanting to for a long time, so when Two orRead More