Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary!

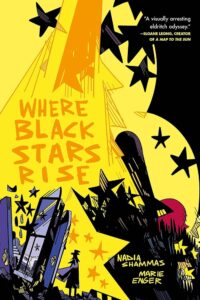

Dr. Amal Robardin, a sapphic Lebanese immigrant who just started working as a therapist, finds herself deeply concerned after the mysterious disappearance of her very first client, Yasmin, a young woman from Iran who has been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Amal feels a responsibility to Yasmin, not only as her therapist but as a fellow Middle Eastern woman trying to find her footing in a new country, far from her family, and where it’s difficult to build a support system. Using the information that Yasmin shared during their therapy sessions, Amal follows these clues to retrace her patient’s steps. When she accidentally falls into an alternate dimension of eldritch horror, she must find her way through the confusion and chaos of this new world to save Yasmin—and herself.

There is, sadly, a tendency in horror for authors and scriptwriters to misappropriate mental illness or use it as a convenient—yet harmful—plot device. Where Black Stars Rise stands out because of its particularly raw, honest, and vulnerable narrative voice. Stories that are centered around mental illness will always be quite heavy, and while this book is no exception, it addresses the topic with such beautiful nuance and even a tinge of heart-breaking hope. Enger, who also has schizophrenia, brought a sense of themself into the characters as well as the captivating world building, all of which made for an extremely emotional reading experience.

Indeed, the design of the alternate world, “Carcosa”, is some of the most harrowing yet stunning art I have ever come across in a graphic novel. Tied in with the character design with which I am deeply obsessed, this book made me an instant fan of Enger’s amazing talent.

Another one of my favourite elements of this story were the conversations that the characters had with regards to family and culture, and how they affect the ways in which we view and understand our mental health. I felt a very personal connection to the characters, especially Amal. Her relationship with her parents is quite complex and nuanced, and while she has a lot of love for her family, she also feels a distance between them because of her queerness and her career choices. This distance is in turn amplified by her reluctance to return and visit them in Lebanon. I so appreciate Shammas and her talent as a writer, and once again, I felt as though she had put a piece of herself into these characters. Being Palestinian-American, it’s clear that the topic of diaspora and having a life and family that is split between the Middle East and the United States was an element of the story that was very personal to her, and it elevated the book that much more.

By the end of this, my jaw was dropped, and tears were freely flowing down my face. As much as it broke me, I loved following these characters through their different, yet intertwined journeys. Shammas and Enger built a truly memorable story, with one of my favourite quotes of all time:

“Most of all? I love that in horror, our storytellers are always right. They’re never believed, they’re cast aside and undermined and left to face the cosmic cruelty alone. But they weren’t wrong. And the readers, the audience? We bear witness to them. We listen, and by merit of their narrative or performance, we believe them in that short burst of time. I want to write that feeling into being. I want to be believed.”

Fans of horror will understand the power of this passage, and readers of all kinds will be able to appreciate the overall chaotic beauty of this wonderful graphic novel.

Representation: Lebanese sapphic main character, Iranian main character with schizophrenia, Black sapphic love interest

Content warnings: mental illness, schizophrenia/psychosis, body horror, blood, gore, suicidal thoughts