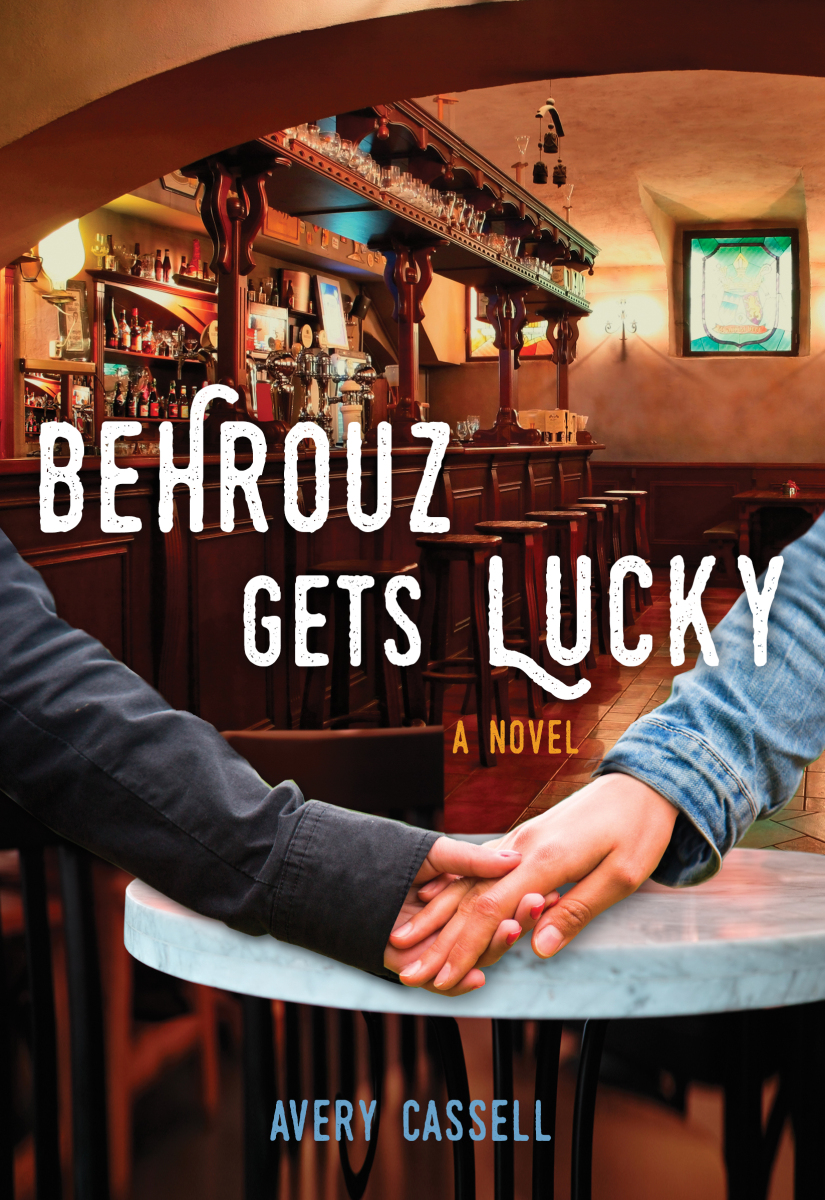

“I wrote this book because I wanted to see more people like myself represented in smut and romance,” writes Avery Cassell in the introduction to Behrouz Gets Lucky (Cleis, 2016), the author’s first full-length erotic romance.

I wanted to see older genderqueer and butch masculine-masculine couples having hot sex and BDSM shenanigans. I wanted to read about people with full lives, lives that included adult children, grandchildren, parents, books, marvelous food, over-the-top drag, and cuddly cats along with lots and lots of hot fucking. I wanted reality, with heartburn, forgetfulness, and aching joints. I also wanted protagonists that cared about San Francisco and were activists, in their own quirky way. And finally, I spent most of my childhood in Iran and love Iran as my other home. I wanted to include a little bit of that amazing and beauteous country in this tale so that my readers could get the chance to love the country too. (viii)

As this paragraph suggests, Behrouz contains an ambitious political agenda and a busy social schedule. I was excited to read this romance because it contains a lot of elements that I typically loved to see in my romance novels: queer characters, older characters, characters with mixed racial and ethnic cultural experiences, a lot of domesticity alongside political awareness and people having sex. Unfortunately, although I am still rooting for all of these things to happen, and happen more often, in romance literature, Behrouz felt more like a rough first draft than a finished novel.

Behrouz is strongest when it comes to the (many and varied) sexual encounters between the title character, Behrouz, and their lover and eventual spouse Lucky. Lucky and Behrouz meet online through OKCupid and after a three-hour first date at a local coffee shop return to Behrouz’s apartment to get it on. Both characters identify on the transmasculine end of the gender spectrum and this work succeeds in its mission to create delicious sexual intimacy between these two characters whom most cultural narratives suggest are too similar to enjoy — let alone sustain — sexual chemistry.

Where Behrouz falters is in the extra-sexual narrative, which often feels like dense authorial notes on plot development, setting, and character description than they do finished prose. I kept wanting to say “slow down and show me this happening rather than tell me it did!” Too often, the characters — secondary ones particularly — failed to emerge out from under their representative types. Self-aware typecasting can, at its best, allow an author to paint a loving portrait of a well-known place or community (think the early installments of Armistad Maupin’s Tales from the City) — and Behrouz at its best reaches toward a smuttier version of the sort of episodic ode to the Bay Area of the pre-Google age that is Maupin’s forte.

Yet overall, narrative shortcuts mean that the reader is given a list of physical descriptors, identity labels, and group affiliations that end up standing in for three-dimensional individuals. To give two such examples, both drawn from the same scene in which Behrouz and Lucky host a potluck for their friends shortly after becoming a couple:

Maxwell looked long at Lucky and me, Lucky in her 501s, aqua linen button-down shirt, mustard-and-aqua windowpane wool waist-coat, and Wescos, and I in my black pleated pants, pink-and-gray floral shirt, dark-gray knitted necktie, and black-and-red cowboy boots. (48)

I’d forgotten about how judgmental people could be, particularly when others start coloring outside of the lines. Masculine-masculine couples were not common in the dyke and queer community, and many folks saw masculine pairings as distasteful, taboo, and unnatural. Or only good for tricks, something to relieve the itch if there wasn’t a femme around. There were a smattering of dyke and genderqueer Daddy-boi couples in the kink community, but they were mostly people under the age of forty. Dykes, queers, and transmen over the age of forty were pretty strongly invested in butch-femme or FTM–gay men dynamics. There was even the Butch-Femme Social Group, and TM4M Cruising Night at Eros for transdudes and gay men. (48)

In both of these instances, important markers of identity (clothing choices) and the social-political dynamics a particular moment within San Francisco’s queer subculture are condensed into lists of attributes and identity affiliations that stand in for character and plot development. I wanted to say, “These are your research notes … now go write me a story.”

Another facet of the social-political at work in Behrouz is the titular character’s identity as an immigrant.Behrouz’s experience as a Persian-American genderqueer individual — “I’m Middle Eastern to my part-American core” they observe early in the narrative (3) — is given scant attention until the second half of the book, when the couple travels to Tehran. I was disappointed not to have a better sense of Behrouz’s experience as a queer American of Middle Eastern descent in the post-9/11 era.

I also had concerns about the way the couples’ visit to Iran, which involves the decision to marry so that they can pass as a straight couple while abroad, serves as touristy background to the American queer experience. The cross-cultural encounter is, of course, complicated by the fact that Behrouz, like the author, spent part of their childhood in Iran. Yet as Americans with American passports and established lives in San Francisco, Behrouz and Lucky interact with Tehranian culture as outsiders, not insiders, and that privilege is not allowed to really settle into the bones of the narrative, with all of its complex implications for individual and collective meaning.

Overall, Cassell’s first novel is an ambitious project that delivers on its promise to represent “older genderqueer and butch masculine-masculine couples having hot sex and BDSM shenanigans” in erotic romance. I expect that there will be an audience for this book if only for the sexually explicit scenes, which could be read in isolation from the connecting narrative as delicious shorts. The narrative structure around these scenes, however, tries to pack too much into less than two hundred pages of prose. I hope that in subsequent installments — the author indicates they are working on a sequel — the non-erotic elements of the story will be allowed to flower more fully.

David Nilsen says

I’ve had an eye on this book, so it’s good to read an honest review of it. I might have to reconsider checking it out. Thanks.

Avery Cassell says

Thank you for the review, although I’m sorry you were disappointed. The sequel will have considerably more narrative about secondary characters, but I wanted this book to concentrate on Behrouz and Lucky’s courtship.

Could you please repair the formatting in your review? The last half of the review is hyperlinked and dosn’t always appear. Thanks again.

Danika @ The Lesbrary says

Oops, not sure how that happened! The formatting is fixed now.