Content warning for child abuse, alcoholism, incest, domestic violence, dissociation.

This review does contain spoilers.

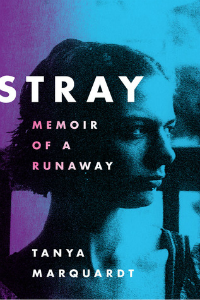

Tanya Marquardt was sixteen years old when she ran away from the home she shared with her mother, stepfather, and assorted siblings in the small Canadian town of Port Alberni. Her flight was strategic, timed right for when Tanya became of age and would no longer be legally bound to her parents’ whims. Her departure began an alcohol-fueled odyssey to manage high school, homelessness, and attempts to process the trauma of a childhood riddled with emotionally manipulative parents and domestic abuse. As young Tanya spirals out, crashing on couches and beds by cashing in on the sympathy of friends, the one constant in her life is a deep love of Shakespeare, and it is that thread that leads her out of the fray and on to calmer waters in her life.

This book is chiefly the honest account of the author’s life detailing a young girl’s family dysfunction and subsequent spiraling out. By fifteen, Tanya was already an alcoholic, and readers will be hard-pressed to find a scene in which she is not chain-smoking. Her unresolved trauma and rebellion against the authoritarian antagonist figure in her life, her mother, eventually leads her to just outside Vancouver, where she says she is living with her formerly abusive alcoholic father but is actually with friends exploring the big city and its underground goth and kink scenes. In these places, she finally finds a home and a tribe to call her own, and through the act of performing and belonging, she finally finds a way back to herself.

I admit that I had a hard time reading this memoir in a number of ways. As an adult, it was hard reading about the struggles young Tanya faced and the many moments where the adults in her life let her down. It was additionally challenging because as a reader, it was hard to know how to feel about the adult figures in Tanya’s life. With young Tanya, in one breath readers experience the psychological warfare her parents commit using her and her siblings as pawns for their own selfish campaigns, and in the other, adult author Tanya chimes in with a throwaway comment about how she loves her family. The result is just one out of a few cases of whiplash, as this story reads more like a history (which, to be fair, this is a memoir) rather than a clearly delineated narrative. It makes for a confusing and sometimes meandering read.

Of particular note for our readers is that while the author self-identifies as a queer performer and playwright today, aside from a passing interest in a female friend at a high school party and mentions of bisexual friends engaging in a few same-sex relationships, all romantic interests and sexual identities explored in this book are presented as heterosexual and cisgender.