Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary!

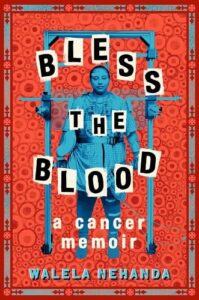

Bless The Blood: A Cancer Memoir is a striking book that gets under your skin and stays there for days afterward. Though billed as a YA book, the writing and story hold a depth of feeling and insight that will engage far older readers, too. Hospitals, homes, intimate relationships and even one’s own skin are explored as sites playing host to complex histories. Framed by references to Cynthia Parker Ohene and Audre Lorde, Walela Nehanda threads a poetics of class, race and gender that shows how those constructs tangibly mediate who has access to certain spaces and their attendant expectations of care.

There is wisdom in Nehanda’s depiction of the ways relationships function as spaces for the people in them. And inversely, how spaces are shaped by the connections people make there. Some books really get to the heart of that old saying “a house is not a home”—this is one of the few that goes further by suggesting that a body isn’t always a home, either.

Teeming with generational trauma and an aching love-hunger that breaks through in paragraphs and poems about sickness, recovery, affection, intimacy, and history, this is a book that refuses to be reducible to inspiration porn. There is a lot of unvarnished pain here: it beats and seeps and leaps out of the page, sinking into the sorest parts of anyone who has ever found themselves at odds with their body, anyone who has ever felt the acute violence of having their bodies treated as alienable.

But these recollections are accompanied by memories of healing and true connection that remind me of one of my favorite aspects of queer media: the defiance of portraying communal moments of revelry and unapologetic joy. These moments offer a small antidote to the seemingly incessant indignities Nehanda encounters in trying to access care through institutions that diminish compassion into a sort of charity contingent on the seeker’s performance of acceptable respectable acquiescence to unjust norms. It is a keenly relevant story, and only becoming more so as the conversation and activism around medical bias gains momentum.

The book’s archetypal figures and icons are also from a media moment that younger readers (I’m including twenty-somethings in this), will find timely. Close readers might be left wondering why there is more “prestige” in the exploits of long-dead hellenics than Captain American or Black Panther—and how our insistence on pretending that the former are more universal than the latter only goes to show how deeply those stories have been decontextualized in service of modern myths about what is “natural” or just.

I will admit fully that I am very partial to this sort of mythic deconstruction. I appreciate authors who staunchly refuse the opiate of presumed objectivity and instead fiercely reckon with the implicit messages and specificity of our shared stories. There is a passion in these pages that I found refreshing, and which I hope this review does justice to.

Who Will Enjoy This: People who thought The Remedy was poignant, timely and want to read more deeply personal stories about the struggles of accessing care (both medical and otherwise) as a gender-expansive person of color (here, a Black person in America). People who enjoy memoirs in verse, or poetry about the poet’s relationship with their body and others. People who think “formalism” is another word for “limitation”. People who enjoy science fiction metaphors for biomedical ideas.

(Seriously, Nehanda’s description of leukemia and their body as a besieged planet is all I’ve been talking about to anyone who will listen for the past week)

Who Might Think Twice: If you’re currently dealing with healthcare bias and difficulties of your own, this book will either reassure you that you are not alone or leave you emotionally exhausted. Your miles may vary. Nehanda pulls no punches in either their remembrances of or their viscerally unflinching depiction of their pain.