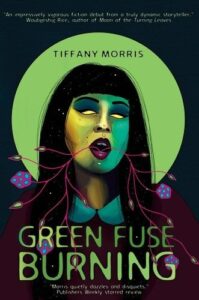

Last weekend was Dewey’s 24 Hour Readathon, which I’ve done every year for the past ten years. For the October readathon, I save up horror and other Halloween-themed books all year to marathon that day. Green Fuse Burning seemed like a perfect choice: it’s a 99-page horror novella with an Indigenous and sapphic main character. So, about fifteen hours into the readathon, I picked it up—and I quickly realized I had miscalculated. This may be a short book, but it’s a challenging and thought-provoking read that demands your full attention.

We meet Rita as she is consumed by grief. Her father passed away recently, and she’s mourning not only him but the severed connection to her Mi’kmaq culture. She is preoccupied with death, seeing it in everything. Her relationship with her girlboss, hustle culture girlfriend is on the rocks. She’s estranged from her mother. She’s creatively stuck, unable to create her art. That’s when her girlfriend reveals that she forged a grant application for her, which has been accepted. She’s supposed to spend time at a remote cabin to create a series of paintings. It’s not something she would have applied for herself—it’s way too much pressure at this time in her life—but she decides to go anyway. There, she begins to hear and see strange things around the cabin.

Each chapter begins with a description of one of the pieces she creates during this retreat, which foreshadow what happens next. We also get illustrations throughout: beadwork by Mikhaila Stevens at the beginning and end, and illustrations at the beginning of each chapter by Kaija Heitland. It’s told nonlinearly, jumping between the present and pivotal times in Rita’s life.

There are many dreamlike moments in this novel: it’s an unsettling, uncanny story that is more about Rita’s internal struggles than an outside monster. She begins to plan her own death, wanting to finish this series and then walk out into the woods and never return. Soon, she’s unable to resist the swamp calling to her.

I found out after finishing Green Fuse Burning that Tiffany Morris is a poet, and that makes perfect sense. This is exactly the kind of horror story I would expect from a poet: beautiful, off-putting, and thoughtful. It’s the kind of book that would benefit from reading slowly, so don’t let the page count fool you: this is one you should let linger. I’ll definitely pick up any other horror that Tiffany Morris writes—I just won’t read it while sleep deprived next time.

“Rita gave herself the same reassurance that all poets and artists and writers give themselves when something was unbearable: perhaps it would be good for her art.”