This is a book I respect, and it’s one I struggled to get through. The subject matter is difficult—not only is it set in a near-future dystopia where prisoners fight each other to the death for a chance at freedom, but it also includes footnotes about the real-life atrocities of the prison-industrial complex. I canRead More

The Beauty of Decay: Green Fuse Burning by Tiffany Morris

Last weekend was Dewey’s 24 Hour Readathon, which I’ve done every year for the past ten years. For the October readathon, I save up horror and other Halloween-themed books all year to marathon that day. Green Fuse Burning seemed like a perfect choice: it’s a 99-page horror novella with an Indigenous and sapphic main character.Read More

A Lush Bisexual Vampire Gothic: Thirst by Marina Yuszczuk

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! Thirst by Marina Yuszczuk, originally published in 2020 and translated this year by Heather Cleary, is a dramatic and lushly gothic novel about two women who a string of circumstances going back over a century bring together in modern day Buenos Aires. Yuszczuk revelsRead More

A Lesbian Road Trip Romcom About Death: Here We Go Again by Alison Cochrun

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! I read Alison Cochrun’s previous book, Kiss Her Once for Me, and liked it, but I was not expecting to love this one quite as much as I did. Some of that is for reasons that will translate to many other readers, and someRead More

A Painfully Realistic Teen Romance: Cupid’s Revenge by Wibke Brueggemann

Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary! I will admit that the cover really influenced me in picking this one up. I think it’s stunning. But I’m glad I did! Tilly is only non-artist in a house of passionate artists, and she’s always felt left out. Her parents don’t really understandRead More

Piercingly Insightful Poetry: The Delicacy of Embracing Spirals by Mimi Tempestt

Bookshop.org Affiliate Link From the epigraph to the end, this book is clear-eyed about its aims and its author’s perspective. Tempestt’s writing draws the reader in as a participant, with mentions of readers, watchers, audiences that are not confrontational, but certainly not abstracted. Reading this collection felt like watching spoken word, or another kind ofRead More

A Dramatic Supernatural YA Horror Read: Here Lies Olive by Kate Anderson

Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Here Lies Olive by Kate Anderson is a young adult fiction novel that follows sixteen-year-old Olive as she navigates unwitting friendships to save a ghost that she accidentally-on-purpose brings into the material plane in order to find out if the Nothing that she saw when she “died” after an allergic reaction is reallyRead More

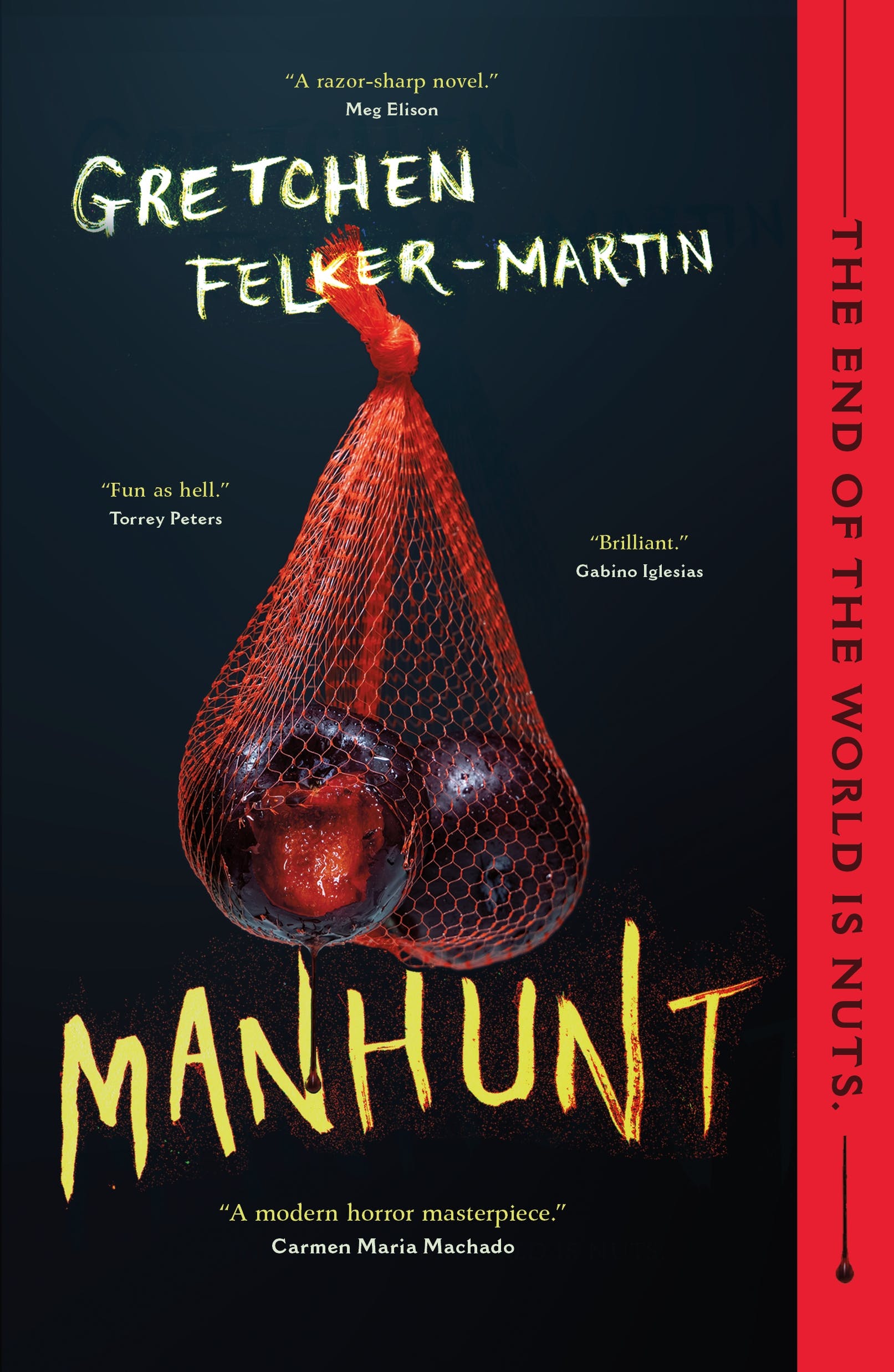

Maggie reviews Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link I knew going into Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin that it was going to be a wild ride. The pair of bloody testicles suggested by the cover tells you that right off the bat. And to tell the truth, I’ve mostly gone off of apocalypse fiction the last few years –Read More

Meagan Kimberly reviews Shadow Life by Hiromi Goto, illustrated by Ann Xu

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Kumiko, a 76-year-old widow, leaves the assisted living facility her adult daughters put her in because it just wasn’t for her. She wants to maintain whatever independence she can for as long as she can. She feels death coming for her, but it’s too soon. So, when death’sRead More

Maggie reviews The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

I’m not going to lie, I did not know if I wanted to read The Pull of the Stars before I started it. I haven’t read a lot of Emma Donoghue before, and I wasn’t aware that The Pull of the Stars had an f/f relationship. I knew that a couple of my friends hadRead More