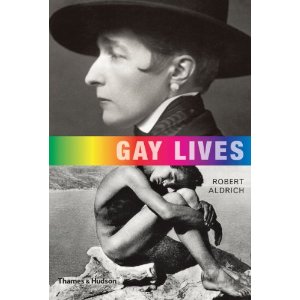

I’ve got to say, as far as first impressions go: this is a beautiful book. It has a gorgeous, soft-to-the-touch dustjacket and tons of high quality photos throughout and thick pages… ah. Sorry, book geeking.

As far as the actual contents, Gay Lives is a collection of short biographies of gay men and women throughout history. I don’t want to get into the argument of calling people “gay” when the term didn’t really exist yet, because they address it, and honestly I find that conversation kind of boring. Gay Lives attempts to cover a large span of time (as in, most of recorded time) and show a global history of gay lives. The biographies themselves are fairly short and succinct, well-written, and interesting. They range from well-known figures (Sappho, Harvey Milk, etc) to more obscure historical figures. They also attempt to show a variety of professions throughout the book.

And this is my main complaint towards Gay Lives: I don’t feel like it was successful in its attempts at diversity. Every time I read a book that claims to be “gay and lesbian” or “LGBT” or some variety, I like to keep track of the content that actual represents each of those categories. In the case of this book, by my count, the number of gay male biographies to lesbian biographies was more than 3:1, and getting close to 4:1. And despite this book containing biographies from a larger range of countries than these sort of collections usually have, the vast majority of the people featured were European. And again, although there are samplings of different professions, the majority of people included are artists (photographers, painters, writers, etc).

I feel a little divided, because this collection does show that they clearly trying to make a more inclusive collection, but having one biography try to sum up all of Africa’s history with homosexuality (or one explaining all of China’s, and one for all of South America’s–Japan gets a chapter) doesn’t quite work. I understand that it is a lot harder to find historical records on lesbians and non-Western queer people, but because the introduction stated that “a particular effort has been made to embrace lives from outside Europe”, I found it to disappointing that the majority of the people featured were Europeans. Often even the more “international” biographies are about Europeans living abroad.

I also didn’t really connect to the structure of this collection. Biographies are roughly grouped by categories, starting off mostly chronologically, then a chapter on women (yes, a contained chapter… sigh), and then chapters on “Visions of Male Beauty”, “Diverse Callings”, “International Lives in the Modern Era”, etc. It didn’t really provide a thread throughout the book. I would have preferred to either see them arranged chronologically or by location.

So on the one hand, this is a beautiful book, well-written, with interesting stories, and admittedly a broader range of subjects than most collections of its kind. On the other hand, I don’t think it exactly lives up to its introduction, and felt a little scattered. I would recommend this if you’re interested in gay male European biographies, but if you’re just in it for the lesbian biographies, I would look for another collection.