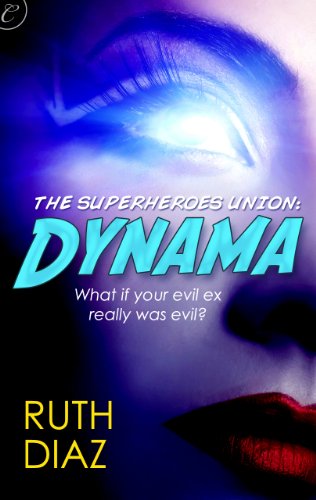

Dynama deftly juxtaposes superpowers around the main romance and both good and bad family relationships. The characterization and dialog make the story, and while not without weaknesses, it offers a satisfying arc despite its novella length. The first scene introduces TJ Gutierrez using her telekinetic powers to help take down a cyborg shark asRead More

Kathryn Hoss reviews Not Your Sidekick by C. B. Lee

Five words: lesbian, bisexual, and trans superheroes. Wait, I think I need a few more. Lesbian, bisexual, and trans superheroes taking on the kyriarchy, falling in love, and just… being kids. Jessica Tran doesn’t fit in. I know, not the most original premise. But along with all the normal crap teenagers worry about– mediocre gradesRead More

Cara reviews Not Your Sidekick by C. B. Lee

The premise of Not Your Sidekick has promise that the execution, unfortunately, doesn’t live up to. The best part of the book is the characterization of the protagonist and her love interest, but everything else falls short. The book opens as Jess, the protagonist and first-person narrator, tests herself for superpowers in the desert nearRead More