I’d looked forward to reading Marriage of a Thousand Lies since I glanced it on Lesbrary, and my initial reaction after finishing it was that of elation, but there was a pit left in my stomach. At first, I couldn’t understand why, but the more I pored over S.J. Sindu’s book, it began to makeRead More

Danika reviews Bearly a Lady by Cassandra Khaw

I will admit, I was sold immediately when I heard “Bisexual werebear novella.” The book opens with Zelda (yes, Zelda) irritated that her transformation into a bear is continually destroying her wardrobe. She works for a fashion magazine, so she doesn’t take this lightly. This is such a fun, light read. It’s quippy and snarkyRead More

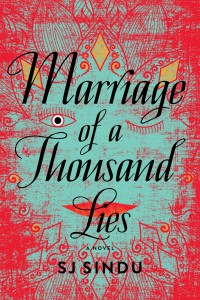

Danika reviews Marriage of a Thousand Lies by SJ Sindu

When Lucky and Kris first got married, they delighted at having pulled the wool over everyone’s eyes. Lucky was welcomed back into her Sri Lanken-American family. Kris didn’t have to worry about getting deported after his family turned their backs on him. And if they both pocketed their wedding rings and went to gay clubsRead More

Danika reviews Riptide Summer by Lisa Freeman

When I finished Honey Girl, I was eager to dive into the sequel–mostly because I was absorbed by the setting (1972 Californian beach culture), but also because Riptide Summer promised to break the rule that “Girls don’t surf.” I’m glad that I got see more of Nani and her life, but overall I didn’t enjoy this oneRead More

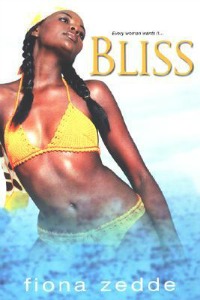

Shira Glassman reviews Bliss by Fiona Zedde

Bliss by Fiona Zedde is a finding-your-place story as much as it is a love story; or you could say it’s a love story between a woman and the self she’s supposed to be or the type of life she’s supposed to be living. It’s also highly erotic, reveling in the sensuality of its characters’ bodies,Read More

Danika reviews Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta

Under the Udala Trees is set in Nigeria during and in the aftermath of the civil war. Ijeoma is sent to live in a safer area of the country with people she’s never meant. She acts as a servant to earn her keep. When she befriends a girl from another ethnic group–in fact, from theRead More

Casey reviews Give It to Me by Ana Castillo

Doesn’t it always seem that the books that you have the highest expectations for are the ones that let you down? That was my experience reading Give It to Me by Ana Castillo, this year’s winner in the bisexual fiction category at the Lambda Literary awards. This novel left me with a lot of mixedRead More

Danika reviews Tell Me Again How a Crush Should Feel by Sara Farizan

I have to start out by saying that I love this title (and the cover is nice as well). Every time I would glance over at the title I’d think Right? What a great encapsulation of the lesbian high school experience. (I also had a Facebook friend comment on my Goodreads post that I had finishedRead More