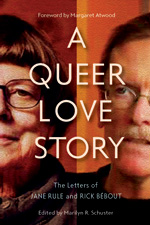

“I expect our letters to be someday public property, and, though I write with little self-consciousness about being overheard at some future date, talking intermittently to you and to myself, it seems to me what has concerned us is richly human and significantly focused on the concerns of our time and our tribe.” – JaneRead More

Anna M. reviews Desert of the Heart by Jane Rule

I became aware of the movie Desert Hearts (1985) when I (like the protagonist of the film It’s in the Water) was scouring my local video stores for movies with lesbian content. It was the mid- to late-90s, and there were still stores with actual videos in them. I have watched Desert Hearts–and Go Fish,Read More

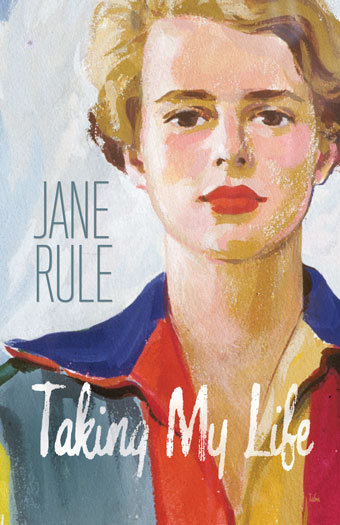

Hannah reviews Taking My Life by Jane Rule

Taking My Life is Jane Rule’s autobiography, yet it was only published posthumously in October 2011. And it might never have been published, had it not been found by chance by Linda M. Morra, a Canadian academic, in an archive box at the University of British Columbia a year after Rule’s death. Since both aRead More

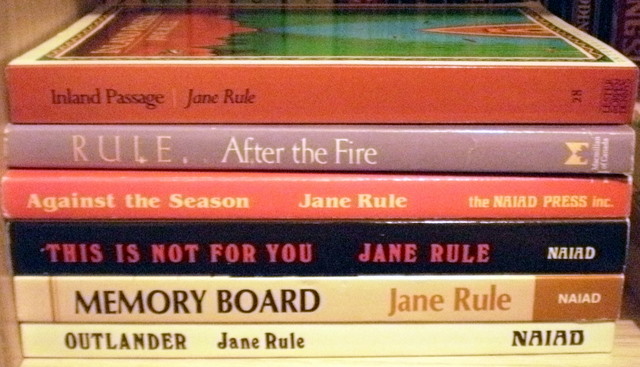

Lesbrary Sneak Peek: Jane Rule

I’m definitely behind in showing off my new les/etc books! Oh well, here are the stack of Jane Rule books I’ve acquired. I think I’ll address these all at once, because I’m excited for them as a whole more than as individual books. Jane Rule is legendary in lesbian fiction. She wrote Desert of theRead More