Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary!

Thirst by Marina Yuszczuk, translated by Heather Cleary (March 5, 2024) is a considered, sorrowful, masterfully atmospheric story about mourning and the costs of surviving outside of society’s protective frameworks. It is also the story of two women in conflict with their inherited and inherent longings around family, companionship and intimacy—one from the past and one from sometime like our present.

Echoes of old-school gothic—in the vein of Rachilde or Poe—permeate Yuszczuk’s prose. And much like those bygone writers, her story is one that poetically captures the complicated moralities of relationships entangled in sociopolitical and material histories.

This is not a vampire romance in the modern sense. The seductions are married to viscera-spilling violence, the decadence marred by decay*, and a sense of bated unsettlement lingers over both the streets and lives our first narrator moves through in her quest for survival. Though she has centuries of experience, she is not immune to the same vices she exploits in others, and is in turn refreshingly slow to condemn them.

The second narrator is much less glamorous. A recent divorcee who’s barely coping with her mother’s terminal illness and hospitalization, our second narrator is struggling but refuses to admit that her white-knuckling isn’t sustainable. That she cannot go on as she always has, that relationships cannot continue in a state of suspended animation. While the past is punctuated by conclusive events and deaths, the present lingers—plastic flowers and medical equipment keep memories alive past well-meaning. We feel the narrator’s frustration, her alienation and desperation and heartache.

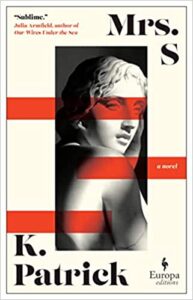

I enjoyed the narrators’ lack of hypocrisy and abundance of interiority. I also appreciated how the novel retains all of their dark and stylistic delight, without the aching inconclusiveness or censor-friendly endings of its pulpy and gothic paperback predecessors—even if the title and cover art are practically begging for an appositive colon.

It’s a clever title, and a colloquial pun. But Yuszczuk’s novel complicates the construction of lust as a base instinct on par with hunger or titular thirst. Lust, desire, eroticism and art are all defiant distractions from the inevitable, and their fulfillment requires the sort of communication and connection that those most basic activities do not.

The second half deals more with grief and more clearly reveals veins of Sheridan Le Fanu’s influence. Some of the scenes reminded me of reading Carmilla for the first time. The tension, the confusion, the delicate language building into bloody, sensual intimacy that is hardly explicit but unquestionably erotic.

Thirst is the sort of book that benefits from second reading or a slow first one. It’s not heavy-handed, but it would be a rich digestif to Gilbert and Gubar’s 1979 opus—and is more than a little likely to appeal to fans of that book. While most of the women’s anxieties are tangible and described in grounded detail, their phantastic responses (as well as the ways wealth, privilege, generational fears and architecture are represented) squarely situate this work within the gothic tradition. I also take this as a historical win— we’re past the period when “hysteria” was a valid diagnosis and when women had to veil lived traumas under layers of metaphor.

As with most translated literature, particularly ones that are heavily descriptive, subtly humorous, or in conversation with historical works, there is a chance that a little something may have been lost in translation. And while I haven’t yet read the original, I can attest that Heather Cleary’s translation maintains a lush, tactile lyricism that swept me into the history, even when the perspective was contemporary enough to reference the recent Coronavirus pandemic.

The vibes were, to put it succinctly, immaculate.

Content warnings: violence, euthanasia

*Some might argue that the close juxtaposition of decay only heightens decadence by contrast. I personally feel that it’s more about how people seek out beauty and small pleasures even in dreary circumstances, but you do you.