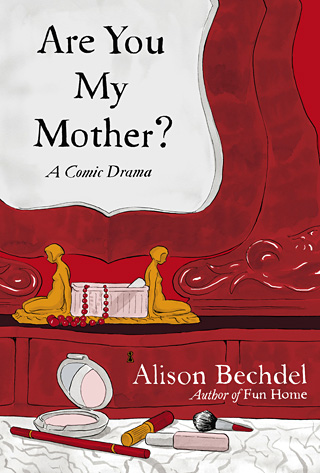

Alison Bechdel’s second graphic memoir Are You My Mother? (2012) certainly has an huge mountain of success to live up to: unbeknownst to Bechdel herself and all her leftist, alternative lesbian Dykes to Watch Out For fans, her first memoir Fun Home (2006) became a best-seller, was named Time magazine’s number one book of the year, and was deemed a best book of 2006 by a ton of other prestigious—and, significantly, non-queer—publications like The New York Times. I absolutely loved Fun Home in all its neurotic glory, literary nerdiness, and heartbreaking exploration of the connections between Bechdel’s queer sexuality and her father’s—latent and closeted as it was. I thus had high expectations for Are You My Mother?, which I’m sad to say weren’t exactly met, although perhaps that was inevitable. Like Fun Home, Bechdel’s new book is an examination of her relationship with a parent, this time her mother. Bechdel’s mother is certainly a worthy character to study: eccentric, artistic, complex, and troubled in many of the same ways Bechdel’s father was. Are You My Mother?, however, doesn’t have the same urgency as Fun Home because it lacks anything close to the burning question that preoccupies Bechdel’s first memoir: is Bechdel’s coming out as a lesbian causally related to her father’s (assumed) suicide just four months later? This isn’t to say that Bechdel doesn’t explore some intellectually fascinating questions about the nature of the mother-daughter relationship in this book, such as the kinds of misogyny that mothers inherit from their own mothers and pass onto their children. In a heartbreaking scene, Bechdel’s mother Helen tells her that the main thing she learnt from her own mother was “that boys are more important than girls”; Helen admits freely that she carried on this pattern of favouring male children, to the obvious detriment of her daughter.

Are You My Mother? follows a circular pattern, as did Bechdel’s first memoir: each section begins with a recounting of an important dream, then meanders through a dizzying narrative moving back and forth in time, recalling different eras of Bechdel’s life, doing close readings of psychoanalytic texts and thinkers, and returning to previously examined scenes and thoughts. The incidents of her life that she chooses to focus on are, obviously, often momentous—at least in psychological terms—events with her mother from her childhood as well as adulthood: one telling such scene is when Helen abruptly tells her daughter, at age seven, that she is “too old to be kissed goodnight anymore.” Here and in other scenes Bechdel expertly captures the rawness and immediacy of childhood emotional injury: when her mother leaves her tucked in bed with a mere “goodnight” Alison feels as if her mother has “slapped her.” The drawing shows Alison shocked and still tucked in her bed with wide open eyes; a thick line of wall divides the two and her mother’s back faces the reader as she walks away. The black and white, red-accented drawings here and everywhere in the memoir are truly exquisite. They’re beautifully expressive, and do a fantastic job of illustrating a narrative that is largely an introspective, inward journey.

Other than her relationship with her mother, the other theme around which Are You My Mother? revolves is Bechdel’s therapy sessions, linked to her obsession with psychoanalysis. Again like Fun Home, this memoir is a highly allusive text: instead of the literary references, like the Icarus and Daedalus myth, however, we have psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s works. I have to say I agree with Danika’s review that I simply didn’t enjoy these allusions as much as the ones in Fun Home. I’m a huge fan of Bechdel’s work and have taken graduate-level courses in psychoanalytic theory and literary and queer theory, but some of the psychoanalytic discussion took a fair amount of concentration for me to follow. Moreover, I found a significant part of it simply not that interesting. A student of psychoanalysis would have a field day with this memoir, as will English and Women’s Studies professors. I’m not sure, however, how much fans of Dykes to Watch Out For and Fun Home, or queer women readers in general, will really enjoy the psychoanalysis and the concentration on Bechdel’s therapy sessions. I found myself feeling impatient with the amount of the book that focused on these topics. Maybe I’m not a child of the 80s enough to sympathize with the impulse for obsessive and life-long therapy (I’m reminded of a Dykes to Watch Out For strip where Sydney tells Mo “I know it’s so 80s, but you have considered therapy?”). I wanted to know more about Bechdel’s “serially monogamous” adult relationships and more about her mother as an individual; Bechdel seems to have made peace with Helen, reconciling herself to the person her mother is by cathartic means of the book, but I left the memoir still unsure as to what exactly made Helen the woman she was (and is). Ironically, Bechdel dedicates the book to her mother, “who knows who she is.” Maybe this dedication means that Bechdel had to let go of any desire she had to know who her mother is, something that readers have to relinquish as well. Cathy Camper at the Lambda Literary site seems to feel left without answers by the memoir as well. Despite my mixed feelings about Are You My Mother?, I would still recommend it to readers who like Bechdel’s other work; I would just advise them to put on as much of an academic, intellectual lens as they have available to them when they pick it up.