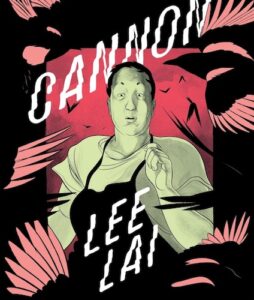

Cannon by Lee Lai is one of the best graphic novels I’ve read this year—a masterclass in building tension through narrative and illustration. The story starts at what seems to be a point of maximum tension, with the eponymous character standing in the carnage of a destroyed restaurant or cafe. We do not know which it is, where we are, or why it’s come to this. We are hit with the shock, then as the pages turn, slowly start to understand the creeping pressures and quiet anguish that finally led to everything burning out and breaking down.

Lucy “Cannon” and her closest friend Trish are difficult women. They are quiet, mostly. Diligent, mostly. Responsible enough. But Cannon is slowly wearing down under the demands of working in a restaurant kitchen under a lecherous, orientalist boss while also providing care for an aging, abusive grandfather whose violence has isolated him from everyone else—and trying to eke out a relationship with an emotionally unavailable woman on top of it all. Meanwhile, Trish is hopping between the bed of a man who wants more than what she’s willing to offer and coffee meetings with a former professor/current mentor figure whose validation seems to be a stand in for something bigger—and who is herself chasing a youthful high predicated on a decidedly unromantic but nonetheless intimate desire for relevance and “edge”. In between this juggling act, Trish quite literally loses sight of her old friend’s perspective and worries (the panels where her interrupting speech bubbles block out Cannon’s add to the rising tension), contributing to Cannon’s increasing emotional load.

(Between this and Cam Marshall’s Flying Saucer Video webcomic, I find myself curiously warming to the portrayal of genuinely well-intentioned, compassionate and caring male romantic interests for bisexual women characters: it lends more agency to the choices the women make about their love lives, and allows for greater exploration of intimate needs, the complexity of desire and all the preconceived baggage that weighs down relationships when misogynistic violence isn’t a plot device to propel them into the arms of a lesbian lover. We don’t need another hero(ine). There’s a more nuanced element of choice, and also more opportunities for character-building conversations to be had.)

Taking the inner tumult and slowly fraying psychodrama of dutifulness that has largely been the purview of writers like Betty Friedan, Natalia Ginzberg, or femme writers whose protagonists of color find themselves unable to reconcile postcolonial expectations of docility and duty with their variegated queer desires and must experience a revelatory rupture with one community in order to resolve their belonging in the other, Lai instead focuses on the quiet, simmering struggles of trying to “have it all” culturally. Of trying to balance filial piety with self-actualization, complicated parent-child relationships with more complicated romantic ones. Of never expecting enough from others but always expecting too much from oneself. It’s a constant tightrope act taut between different sets of internalized expectations. It’s enough to drive anyone to exhaustion, frustration, aggravation.

And that’s before we get to The Birds.

“In spring the birds flew inland, purposeful, intent; they knew where they were bound, the rhythm and ritual of their life brooked no delay. In autumn those that had not migrated overseas but remained to pass the winter were caught up in the same driving urge, but because migration was denied them followed a pattern of their own. Great flocks of them came to the peninsula, restless, uneasy, spending themselves in motion; now wheeling, circling in the sky, now settling to feed on the rich new-turned soil, but even when they fed it was as though they did so without hunger, without desire. Restlessness drove them to the skies again…seeking some sort of liberation, never satisfied, never still…driven by the same necessity of movement…scattered from tree to hedge as if compelled.”

“The Birds” by Daphne du Maurier (emphasis mine)

Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Birds is based on an earlier short story by notably disputedly bisexual member of the gothic horror canon, Daphne du Maurier. There’s an almost cinematic staging to the panels of Cannon running. The visual closes in on her slowly, zoom beats following those of one’s heart if it were to be shot on camera. Her movement, we notice, is fueled by a restlessness not unlike the birds in du Maurier’s story. She listens to meditation and deep breathing audios about relaxation while running hard enough to gasp, tries to “focus elsewhere” while running towards nothing in particular. Tries to give and give of her time and care while being unable to find support for herself.

There are works of fiction that serve less as an escape and more as an inexorable mirror to the things people try to escape from. Through Cannon, Lee Lai meditates on how one can’t keep running from your feelings. You can’t always let them go, move them around, hope they resolve. Can’t always actualize, rationalize, compartmentalize. Sometimes, they need to be reckoned with. To be in community with. Or they end up bursting out in destructive ways (the panels referencing Carrie were a delightfully apt touch).

Lai’s choice of films here is telling. Both Carrie and The Birds are visually almost synonymous with the women at the heart of their narratives. They are about what happens when societal order collapses, when expectations for “the natural order of things” (and people) are upended. About surviving abjection.

And as one of Cannon’s coworkers puts it, “The dystopia is upon us.”

What can care look like in such a state? Community? Calm?

Cannon by Lee Lai is currently available for pre-order and will be on sale 09/09/2025.

Who Will Like This:

– Readers who appreciate realistic middle-aged bodies in their comics. Lai draws women who look like they could be anyone’s aunty: paunch, love handles, saggy breasts and all.

– Readers looking for catharsis from the decay of late stage capitalism and its attendant sense of profound disconnection and the pressures of having to turn the self into a brand, a cohesive narrative, or a fiction stripped of context for the consumption of others.

– Readers looking for literature that affirms that one cannot escape The Horrors, but one can survive them, perhaps even bite back through the help of community. What was that quote by G.K. Chesterton about the dragons and bogeys, again?

– Self-described or institutionally legitimized horror scholars. As mentioned above, the book has a creative and clever understanding of horror films as explorations of anxiety.

Who Might Think Twice:

– Readers who are put off by m/f sexual imagery: there’s a lot of uncovered postcoital conversations in the book that flesh out the characters and their approaches to relationships.

– Also, readers who might be put off by panels referencing horror films and unfortunate memories that are not gory or bloody, but do feature representations of monsters and violence.

Content warning: cheating