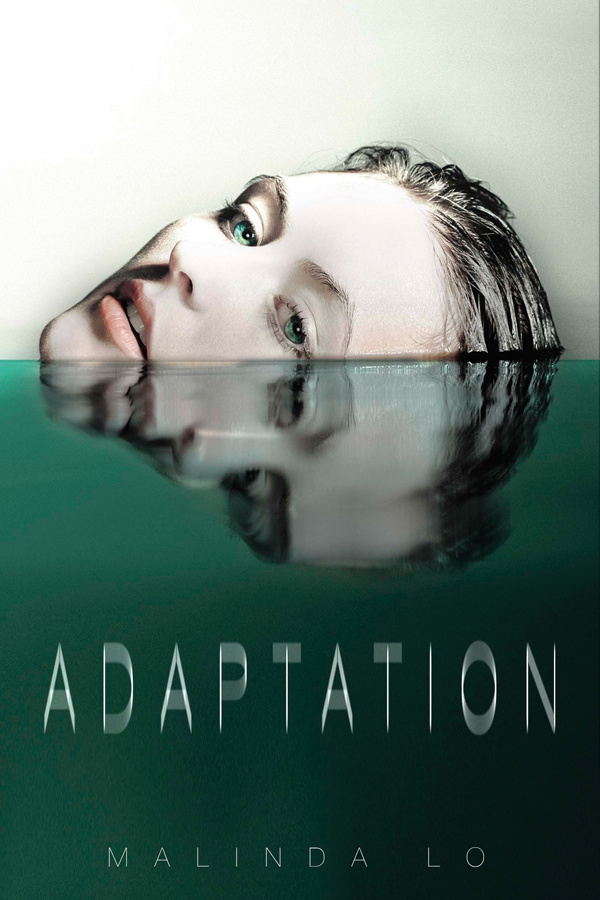

The night I finished reading lesbian author Malinda Lo’s third young adult novel, Adaptation, I dreamt of plane crashes, government conspiracy cover-ups, and my new, super-natural ability to hear the most minute of sounds. In short, it was a restless night—but so worth it.

Adaptation takes place in post-9/11 America in the not too distance future. The bisexual protagonist, Reese Holloway, is away from her native San Francisco with her debate coach, Mr. Chapman, and debate partner, David Li, when planes start to crash all over North America. Their journey home ends in a car crash—and Reese waking up 27 days later, distinctly but indescribably different than she was before. What ensues is a quest to understand what exactly is going on set alongside Reese’s exploration of her feelings for David—and a girl who, literally, knocks her over on their first meeting.

With much success, Lo delivers a fast-paced science-fiction page-turner coupled with a queer teenage romance in its most complicated form. Lo also provides refreshing diversity in her cast of characters without it ever feeling didactic; more simply, her text reflects the racial and sexual diversity of San Francisco as well as gifting our near-future with a few less gender constraints. If you’re a sci-fi lover, X-files nerd, or a fan of contemporary queer YA, you’re definitely in for a treat.

Lo has also written Ash, a lesbian re-telling of Cinderella, and its companion novel, Huntress. Adaptation is the first in a duology, with the second novel due out in September 2013.

Check out more of Erica’s writing at So You’re EnGAYged and on Twitter @eoflovefest.