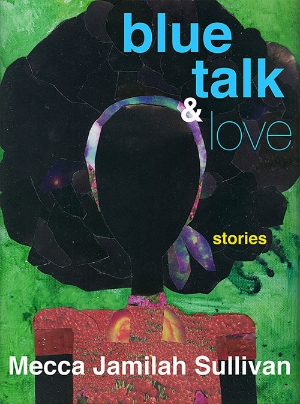

Trigger warnings: Rape threats, mild violence, fat-shaming. As soon as this book was released I knew I had to have it. Stories about Black queer women written by a Black queer woman? Yes, please! I was a little worried that I wouldn’t connect to them; they are all set in and around New York City,Read More