Buy this from Bookshop.org to support local bookstores and the Lesbrary!

My girlfriend’s and my 10-year anniversary was this month, and I figured it was well past time we bought our own volume of Sappho.

For those who don’t know, Sappho was a poet from the island of Lesbos who lived around the turn of the 6th century BC. In her day she was known as “the Tenth Muse,” and though her lyric poetry and songs were some of the most influential in the ancient Greek language, only fragments of her works survive. It’s from her legacy that both the terms sapphic and lesbian are derived.

Unsurprisingly given how iconic her work is, there have been many translations of Sappho’s poetry published over the years, and it’s amazing how different they can be. Now, translation, as an art form, is often not given the credit it deserves. There’s a dream our culture has of a passive, invisible translator, someone who can provide the pure, unaltered meaning of a text without inserting anything of themselves in the process. It’s an impression of translation people get from foreign language dictionaries and algorithms like Google Translate; this idea that perfect, impersonal translations between different languages is ideal, or even possible. The truth is, however, that it isn’t reality. Translators are active participants in the writing process, just as authors are. This becomes especially clear with poetry—the density of meaning that each word has in a poem starkly illustrates just how difficult and creative the task of translation is.

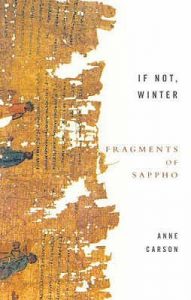

Thankfully, I knew exactly which version of Sappho I wanted to get—Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter: Fragments of Sappho. Carson is a prolific and well-respected translator of ancient Greek works, and tends towards starkly simple and evocative language in her translations. If Not, Winter is that in the extreme; each page is mostly blank, with one to a handful of fragments on them. The reverse of each page holds Eva-Marie Voigt’s transcription of the ancient Greek, but even if you can’t read any of it at all, Carson’s English translation is more than compelling enough. What strikes me most about it, especially over other translations, is just how obviously fragmentary every piece of a poem is. Carson calls attention to where pieces of the original poems are missing with heavy use of open brackets and line breaks, and the effect is immediate and profound. Just flipping through, there’s no mistaking that you’re reading the scattered shreds of a much larger body of lyric work. Carson also avoided inserting words not present in the original Greek whenever possible, even when doing so sacrifices the clarity that articles or pronouns might provide. Everything feels short, poignant, bittersweet—the echoes of great words, great loves, barely remembered.

Of course, if a translated work benefits from its translator’s talent and vision, so too is it influenced by their biases. There are a few small things in If Not, Winter that felt oddly hesitant with Sappho’s, well, sapphic legacy. Carson’s introduction mentions that Sappho loved women deeply, and adds, “Can we leave the matter there?” Her description of Sappho’s family includes a husband and a daughter, despite the fact that evidence of either are extremely sparse and potentially suspect; for these details she cites only “biographical sources,” when the rest of the introduction is full of far more specific and thorough citations. Many women that appear in the fragments themselves are described in the appendix as “possible companion[s] of Sappho,” while her brother’s lover is explicitly given as his “girlfriend.” All this is just the supporting material, though—with the translation itself, I’ve only taken issue with one thing so far. This may be extremely nitpicky of me, but in fragment 102, Carson translates παῖδος—a word for a young person—as “boy,” even though “girl” would be just as accurate, and “youth” more accurate still. I’ve seen other classicists confused by this choice as well; it’s usually the one main complaint about an otherwise stellar translation.

That said, I’m overall quite pleased with If Not, Winter. There’s something extremely powerful about looking at words written more than two and a half thousand years ago and reading them, simply stated, on a blank page—seeing a single recovered noun or adjective, and knowing the whole song that once held it was sung across the entire ancient Mediterranean world. That’s the bittersweet thing about Sappho: so much has been lost, but also, what a miracle that this much has been saved! I do appreciate that Carson leans into this heart-wrenching contradiction by not covering up the holes in our knowledge, and fully embraces what’s left as, well…fragments of Sappho. Because the beautiful truth is that despite it all, despite what people may say or think, despite how much of the Tenth Muse’s music is gone forever, we do remember her—even here, in another time.