Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link This dark fairy tale dances on the line between fantasy and horror. It follows Devon, a book eater, who is part of one of the aristocratic houses of book eaters (think vampires, but they eat books instead of drinking blood). She is one of very few women bookRead More

Maggie reviews Galaxy: The Prettiest Star by Jadzia Axelrod

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link In Galaxy: The Prettiest Star, Taylor has a life-threatening secret. She is the Galaxy-Crowned, an alien princess hiding on Earth from the invaders that destroyed her home as a baby. Taylor’s guardian fled with her and two others to Earth, disguising themselves not only as humans, but alsoRead More

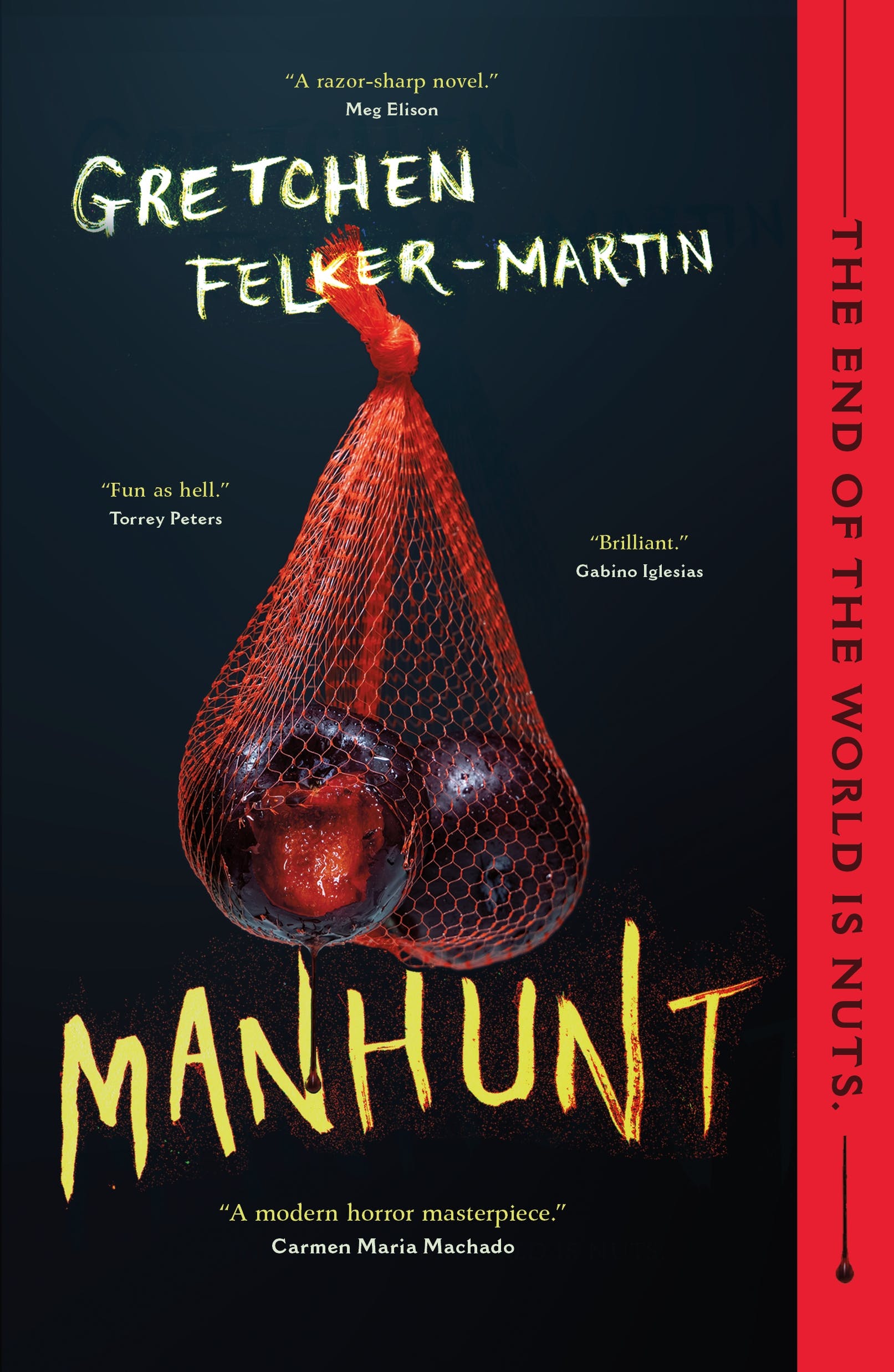

Maggie reviews Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link I knew going into Manhunt by Gretchen Felker-Martin that it was going to be a wild ride. The pair of bloody testicles suggested by the cover tells you that right off the bat. And to tell the truth, I’ve mostly gone off of apocalypse fiction the last few years –Read More

Anna N. reviews Heathen by Natasha Alterici

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Aydis is a Viking and warrior, raised on stories of wartime valor and battlefield sacrifice by a father who taught her things “unbecoming” of a woman. But she is also sincerely kind, more likely to reach out a hand than draw her sword against a stranger. She isRead More

Nat reviews Plain English by Rachel Spangler

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Rachel Spangler is probably one of my most read authors of sapphic romance because they are so darn reliable. I’ve never been disappointed. In my mind, I often refer to Spangler as “the author who writes sports romance,” and yeah, I’m a big sucker for a feel-good sportsRead More

SPONSORED REVIEW: Middletown by Sarah Moon

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link Eli and Anna know the routine. The cops come to the door in the middle of the night, Eli tries to look as young and adorable as possible, then Anna puts on eyeliner, grabs a beer from the fridge, and tries to sweet talk them into looking theRead More

Danika reviews Kimiko Does Cancer: A Graphic Memoir by Kimiko Tobimatsu, illustrated by Keet Geniza

Kimiko Does Cancer is about about a queer, mixed-race woman getting breast cancer. This is a short book, only 106 pages, and it moves quickly: the first page is about Kimiko finding a lump above her breast, and then it moves through her diagnosis, treatment, and the aftermath. Tobimatsu explains in interviews/articles that she wantedRead More

Meagan Kimberly reviews Gender Flytrap by Zoe Estelle Hitzel

For National Poetry Month I chose to read this collection I’d picked up from Sundress Publications, an independent press. It’s a fascinating collection of poems about the interconnected nature of gender, sexuality, sex, and identity. The poems’ forms start as stanzas and lines written in fragments, but as the speaker gains a greater sense ofRead More

Anna Marie reviews Stone Butch Blues

Ever since I learnt about Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg I’ve wanted to read it, but I knew it would be an intense book to read with quite a lot of violence in it, so I waited till I thought I might be slightly more ready for it. The time to read it arrived since, lastRead More

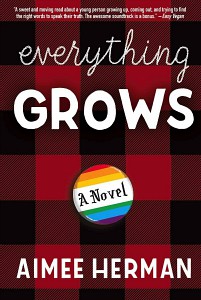

Mallory Lass reviews Everything Grows by Aimee Herman

CW: suicide, homophobia, family trauma, parental character death (remembered) and child abuse Have you ever picked up a book and the whole time you’re reading, it feels like somehow the universe aligned and you were meant to find it, to soak in the words and glide through the pages? Well this is how Aimee Herman’sRead More