I recently attended a literary conference focused on lesbian literature and was shocked at how many attendees didn’t know anything about Black lesbian literature outside of two or three authors. Most were familiar with Jewelle Gomez’s The Gilda Stories, which celebrated its 25th anniversary this year, and Audre Lorde, the consummate Black lesbian poet, but that was about it. Full disclosure: I wrote an entire dissertation on the marginalization of Black lesbian literature, so I might know more about Black lesbian books than the average lesbian literature lover. Still, here are a few titles that you’ve probably never heard of, but that you should definitely read. This month I’ll discuss five titles, and I’ll finish up the list later this year.

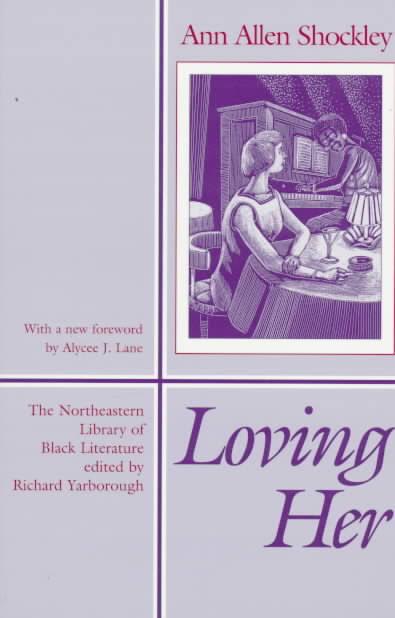

1. Loving Her (1974). Ann Allen Shockley is generally hailed as the first Black lesbian novel published in the United States, i.e., the first novel written by a Black lesbian with a Black lesbian protagonist. Loving Her, while at times overly didactic, is the novel upon which the Black lesbian literary canon is built. The novel’s themes are overtly political, mostly in relation to the Black Nationalist and feminist rhetoric of the time, but these topics are still relevant today, and particularly given our current political climate. The novel centers on Renay, a working class Black musician married to the abusive, failed football star, Jerome Lee; and Terry, the rich white woman writer who falls in love with her. Loving Her goes back and forth in time, as it relates the story of how Renay and Terry met, as well as the challenges they faced as a couple. There is a bit of drama, but you’ll have to read the novel to find out what that is! As mentioned earlier, the writing can be a bit heavy at times, but this book is an excellent look at how one writer represents an interracial lesbian relationship.

1. Loving Her (1974). Ann Allen Shockley is generally hailed as the first Black lesbian novel published in the United States, i.e., the first novel written by a Black lesbian with a Black lesbian protagonist. Loving Her, while at times overly didactic, is the novel upon which the Black lesbian literary canon is built. The novel’s themes are overtly political, mostly in relation to the Black Nationalist and feminist rhetoric of the time, but these topics are still relevant today, and particularly given our current political climate. The novel centers on Renay, a working class Black musician married to the abusive, failed football star, Jerome Lee; and Terry, the rich white woman writer who falls in love with her. Loving Her goes back and forth in time, as it relates the story of how Renay and Terry met, as well as the challenges they faced as a couple. There is a bit of drama, but you’ll have to read the novel to find out what that is! As mentioned earlier, the writing can be a bit heavy at times, but this book is an excellent look at how one writer represents an interracial lesbian relationship.

2. 25 Years of Malcontent (1976) and A Distant Footstep on the Plain (1983). Stephania (Stephanie) Byrd’s poetry centers the experiences of Black lesbians in the early years of the feminist movement. She writes of communes, the danger of being an out lesbian, as well as the joy she finds in communities of women who love women. You’ve probably never heard of her, but her poetry is not to be missed. The imagery is at times a bit stark and gritty, but that speaks to the veracity of her perspectives on Black lesbian life. [Available to download for free here.]

2. 25 Years of Malcontent (1976) and A Distant Footstep on the Plain (1983). Stephania (Stephanie) Byrd’s poetry centers the experiences of Black lesbians in the early years of the feminist movement. She writes of communes, the danger of being an out lesbian, as well as the joy she finds in communities of women who love women. You’ve probably never heard of her, but her poetry is not to be missed. The imagery is at times a bit stark and gritty, but that speaks to the veracity of her perspectives on Black lesbian life. [Available to download for free here.]

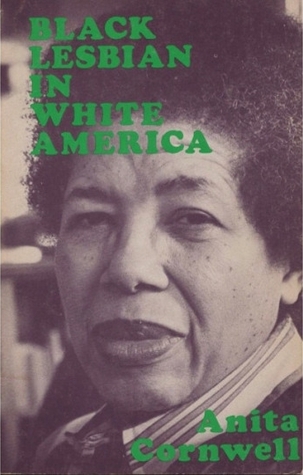

3. Black Lesbian in White America (1983). Anita Cornwell was calling out patriarchy, homophobia, and racism before most of us were born. She was a lesbian separatist, which may have made her unpopular in Black as well as some lesbian and feminist communities. This collection of essays is important, though, because she was clearly invested in writing about the experiences of women and creating a world where all women could be free. She was also one of the only Black lesbian writers to publish essays in Negro Digest and The Ladder. Check her out!

3. Black Lesbian in White America (1983). Anita Cornwell was calling out patriarchy, homophobia, and racism before most of us were born. She was a lesbian separatist, which may have made her unpopular in Black as well as some lesbian and feminist communities. This collection of essays is important, though, because she was clearly invested in writing about the experiences of women and creating a world where all women could be free. She was also one of the only Black lesbian writers to publish essays in Negro Digest and The Ladder. Check her out!

4. For Nights Like this One (1983). Becky Birtha’s collection of stories explores issues of loss, family, motherhood, and acceptance in lesbian communities, and like Ann Allen Shockley, she also wrote stories that included interracial relationships, mainly between Black and white women. One of my favorites is “Babies” which is about a woman who longs to have a child, but gives up that dream to be with the woman she loves. It may seem ridiculous now, but at the time, many lesbians considered having children complicity in patriarchal system, and they wanted no part of it. Don’t believe me? Visit your local library and check out a few books on lesbian separatism. More than anything, this collection of short stories reveals the myriad ways in which Black lesbians experienced life and love, and although not all of the stories have happy endings, one gets the sense that Birtha’s lesbians are unafraid to face life on their own terms.

4. For Nights Like this One (1983). Becky Birtha’s collection of stories explores issues of loss, family, motherhood, and acceptance in lesbian communities, and like Ann Allen Shockley, she also wrote stories that included interracial relationships, mainly between Black and white women. One of my favorites is “Babies” which is about a woman who longs to have a child, but gives up that dream to be with the woman she loves. It may seem ridiculous now, but at the time, many lesbians considered having children complicity in patriarchal system, and they wanted no part of it. Don’t believe me? Visit your local library and check out a few books on lesbian separatism. More than anything, this collection of short stories reveals the myriad ways in which Black lesbians experienced life and love, and although not all of the stories have happy endings, one gets the sense that Birtha’s lesbians are unafraid to face life on their own terms.

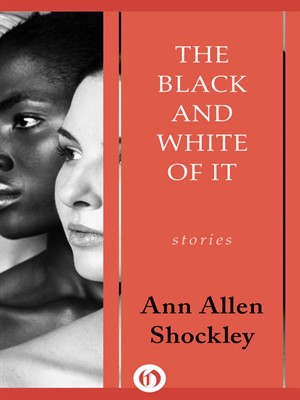

5. The Black and White of It (1980). Ann Allen Shockley’s collection of short stories offers up snippets of lesbian life in the late 1970s. The stories examine issues of loneliness, internalized homophobia, and racism, and more often than not, lesbians living in the closet. A white college professor falls in love with her out graduate student, but can’t free herself from the closet to make the relationship work. A Black politician rejects her lover because she refuses to disavow her lesbian identity. While several of Shockley’s lesbians lead droll, closeted lives, they provide a window through which readers can experience what it might have been like to be lesbian in the latter part of the 20th century.

5. The Black and White of It (1980). Ann Allen Shockley’s collection of short stories offers up snippets of lesbian life in the late 1970s. The stories examine issues of loneliness, internalized homophobia, and racism, and more often than not, lesbians living in the closet. A white college professor falls in love with her out graduate student, but can’t free herself from the closet to make the relationship work. A Black politician rejects her lover because she refuses to disavow her lesbian identity. While several of Shockley’s lesbians lead droll, closeted lives, they provide a window through which readers can experience what it might have been like to be lesbian in the latter part of the 20th century.

Black lesbian literature as a genre has grown since these titles were first published, and there are literally hundreds of titles now available that readers can choose from. However, I think it’s important for readers to know that Black lesbians have a literary history too. All of these authors are still alive, and some are still writing. Shockley published her last book, Celebrating Hotchclaw, in 2005; and Birtha is the author of several children’s books. The next time you’re in the mood for a little classic lesbian literature, check out one of these titles. And the next time you’re at a conference or book festival and someone says they don’t know anything about Black lesbian literature, tell them about these amazing writers!