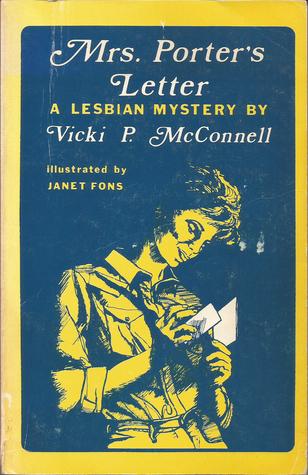

Mrs. Porter’s Letter , published in 1982, is one of the first four lesbian mysteries ever printed—and only the second to develop into a series. It was followed over the next several decades by hundreds of other novels featuring lesbian sleuths. Yet the novel’s influence seems small in comparison to some of f the other early authors of lesbian mysteries, such as Eve Zaremba (who created the private investigator Helen Keremos) and Katherine V. Forrest (whose police detective, Kate Delafield has become an icon). Few critics seem to have paid much attention to McConnell. Either no one was influenced by the book, or no one bothered to read it. What a mistake, because it is decidedly and mysteriously different from almost everything that came later.

The book, featuring fledgling writer Nyla Wade, is on the surface a modern Gothic search for the owner of a desk that Nyla comes to possess, although it has a very noir subplot involving the murder of a prostitute. Most important, though, it is Nyla’s search for her own intellectual and sexual identity. This is very rare in a genre dominated by out-and-out dykes, closeted (like Kate Delafield) or not (like Helen Keremos). Nyla, throughout most of Mrs. Porter’s Letter, is neither.

In fact, Nyla is one of the few protagonists in the lesbian mystery genre who has been married to a man. But Nyla is divorced now and living on her own, getting back into her first love—writing—both for a living and as a creative outlet. To this end, she buys an antique desk, which turns out to contain the spirit and essence—not to mention some love letters—of its previous owner.

Nyla is an intriguing and very likable character with more moxie that I had expected. McConnell, her creator, is adept at showing us her many sides, including very real fears about a single woman living alone in a dangerous city. Luckily, Nyla has a best friend, Audrey Louise that she can discuss things with. McConnell draws Audrey Louise, with her flummox of a husband and three complaining children, with a sympathetic pen. Although Nyla has strong feminist leanings, it doesn’t seem as if she has even given the slightest thought to the idea of identifying as a lesbian—until she actually meets a few.

The novel takes Nyla on a thousand-mile journey to search for the writer of the letters she finds—and to unravel the 30-year history of a hidden love affair. In the process she is finally able to realize why her marriage was not a success and why she has such powerful feelings for a woman she meets in a bar.

Slipshod editing in places is to be expected in early Naiad Press books, but the ones found here rarely detract from the enjoyment of reading. But the lack of seamlessness to the story is another matter. A good—or even a decent and sympathetic—editor, could have guided McConnell through the complex plot and suggested ways in which it would actually achieve more cohesiveness and believability. As it is, the reader gets the idea that McConnell began the novel with no real idea how to end it.

With this and other problems, it can’t be ranked among the best in the genre, but its early publication date makes it a must for students of the lesbian mystery genre. An additional quirk is the fact tat this book and its two sequels are illustrated—probably the only lesbian novels I have seen that are. Sadly, all of McConnell’s books seem to be out of print and unavailable in e-book form. This needs to be corrected.

For 200 other Lesbian Mystery reviews by Megan Casey, see her website at http://sites.google.com/site/theartofthelesbianmysterynovel/ or join her Goodreads Lesbian Mystery group at http://www.goodreads.com/group/show/116660-lesbian-mysteries

David Nilsen says

I wasn’t aware of this author of early lesbian mysteries. Thanks for the tip.