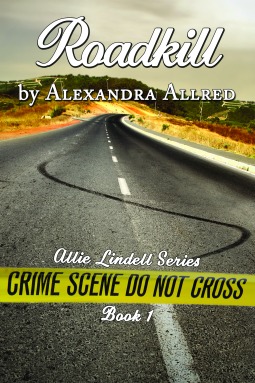

The general conceit about most established fictional detectives is their lack of home life. Either because of the job or because of their need for the job, Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot and Sam Spade don’t really have a lot else going on. The opposite is true for Allie Lindell, Alexandra Allred’s doggedly determined protagonist of “Roadkill.” She has a full-time job in being a mother to two small children and all the responsibilities that come with running a household. In her limited spare time she investigates leads from her friend writing for the local crime beat, using her cop sister as a sounding board and neighbor as willing partner.

The story follows Allie as she investigates two separate cases – the murder of a former policeman and an apparent serial killer dumping the bodies of his victims on the highway. Under the pretense of writing for various fictional news sources, Allie manages to worm her way into all the situations she needs to unravel what turns out to be a thoroughly sordid series of events.

Although the plot does drag at times, all lose ends are dutifully accounted for and it does stay true to what Allred seems to be trying to do: give motherhood its due. Allie does leap, sometimes foolishly, after ever lead she finds, but she does it while juggling babysitters and groceries and an increasingly frustrated wife. It’s an impressive feat even if it takes away from the flow of the book and its implied narrative conceit.

Allie herself is an interesting character, whose flaws make her likeable even if she isn’t the best narrator. She’s deliberately one-sided, blinded by her view of the world, and prone to tangential monologues about the world that could be illuminating if they linked back to the plot later. Despite the book’s impressively complicated plotlines, the most interesting part was the way Allie’s marriage seems to hobble along despite the strain from both women. Allie is presented as a devoted, but bored stay-at-home mother who gave up her job to look after her two children. Private investigation is a side gig to get her out of the house even if she has to bring her children with her to stakeouts. Her wife, Rae Ann, works nights and plays on what seems likes an incredibly time consuming softball team. There is a well-developed web of outside female support who as babysitters and accomplices for Allie and her work – roles that one might think would be taken by a wife or partner. While the obvious object of Allie’s devotion, Rae Ann doesn’t physically appear until fifty pages into the book, and never sticks around long. Allie and Rae Ann are almost comically unsympathetic to the each other’s problems and Allie, at least, is conflicted by the tension between frustration of misunderstanding and the blinding need to forgive and excuse the person she loves. Allred also doesn’t shy away from the effects of marital strain on children and the repercussions of Allie’s fights for her children. Watching the marriage teeter is almost more interesting than Allie’s detective work, but when the conflict does finally does come to a head, it’s ultimately unfulfilling.