Kimiko Does Cancer is about about a queer, mixed-race woman getting breast cancer. This is a short book, only 106 pages, and it moves quickly: the first page is about Kimiko finding a lump above her breast, and then it moves through her diagnosis, treatment, and the aftermath. Tobimatsu explains in interviews/articles that she wanted to write this book because the mainstream narrative around cancer didn’t include her experience. She wanted other queer people with cancer to have a reference that better reflects their lives.

Kimiko Does Cancer is about about a queer, mixed-race woman getting breast cancer. This is a short book, only 106 pages, and it moves quickly: the first page is about Kimiko finding a lump above her breast, and then it moves through her diagnosis, treatment, and the aftermath. Tobimatsu explains in interviews/articles that she wanted to write this book because the mainstream narrative around cancer didn’t include her experience. She wanted other queer people with cancer to have a reference that better reflects their lives.

For one thing, she comes into this experience already skeptical of doctors, especially around sexual health. One panel shows a doctor saying, “Only women who sleep with men need Paps,” (labelled on page as “Bad medical advice”). This is something that I was also told by a doctor, after she blushed and seemed flustered when I told her my sexual experience was with AFAB people. Although she’s grateful for her medical team, she also finds it overwhelming, especially when they give different advice. She also continues to face similar microagressions: a doctor who assumes she’ll immediately want reconstructive surgery on her breast before asking her–Kimiko had been interested in exploring what a mastectomy would mean for her exploration of gender. Later, another doctor asks if she’d like both breasts enhanced as long as they’re “plumping” one.

In her article on Rethink Cancer, she explains,

I didn’t want to talk about how to recover my sense of femininity despite breast scars and menopause; I wanted to explore how losing my breasts might allow me to lean into my masculinity. I didn’t want to talk about how changing femininity could affect a hetero relationship; I wanted to talk about the implications of breast cancer on queer relationships between women.”

This genderizing of breast cancer extends outside assumptions around patients’ relationships to their breasts. In “Straight Cancer in a Queer Body” at The Polyphony, Tobimatsu explains,

Whether we know it or not, ideas around gender are frequently at the forefront of conversations about breast cancer. Little is as connected to notions of femininity as breasts, hair and fertility – all things that can be lost following a breast cancer diagnosis. Perhaps for this reason, society’s response to the disease is to throw pink ribbons, make-up tutorials and a peppy outlook at the problem. For many queers and gender non-conforming folks, this feminization of the disease is stifling…

Not only is Kimiko uncomfortable with the whiteness and heteronormativity/gender norms, she also is alienated by how apolitical these spaces are. Kimiko considers the ethics and greater implications of each of the choices she’s making in this journey, and the structure around them. She recognizes the privilege she has to be in Canada and have the medical support she does, and the special treatment she gets as a young cancer patient. She contemplates the ethics of freezing her eggs for $7,000 when she’s not sure whether she even wants kids–or whether it’s ethical to bring kids into a climate crisis. On top of that, she feels pressure to have had some great epiphany as a cancer survivor: to have a whole new outlook on life, and no longer care about the “little things.”

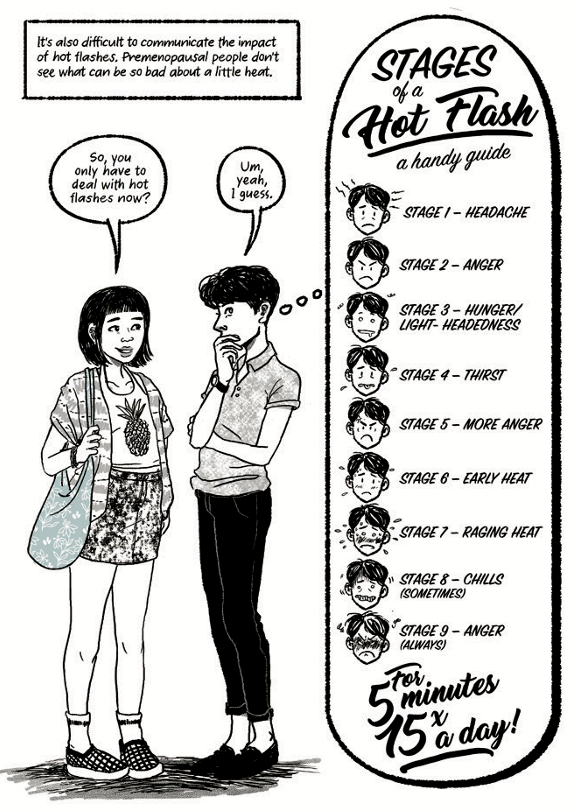

Kimiko Does Cancer follows the aftereffects of her treatment as well. She has menopause induced to (hopefully) prevent cancer from recurring. This leaves her with hot flashes, which play a major role in her life. I had no idea what having hot flashes really entailed:

I highly recommend this book, and I hope that it finds its way into the right hands. I’ll leave off with one last quotation from the author, who explains the importance of changing this narrative. She explains that vague cancer fundraisers often get more attention than specific actions needed to improve marginalized peoples’ lives. (And of course, it’s all connected: racial justice and ending poverty are inextricably linked to health.)

When we centre certain bodies and not others, it has dire consequences – black women with breast cancer get diagnosed at later stages than white women and have lower survival rates… By depoliticizing cancer, it becomes an easy cause to support. Pink ribbon campaigns offer a way to give money to an easy-to-sympathize-with-cause that doesn’t force engagement with more difficult issues like poverty or racial justice.