It’s the classic story: girl meets granddaughter of pastor, girls falls in love, girls get caught and sent away to separate countries. That is only the beginning, though. Audre loves her Trinidad home, and she is heartbroken to leave it–and her love, and her friends, and her family–behind. Her grandmother assures her that Spirit livesRead More

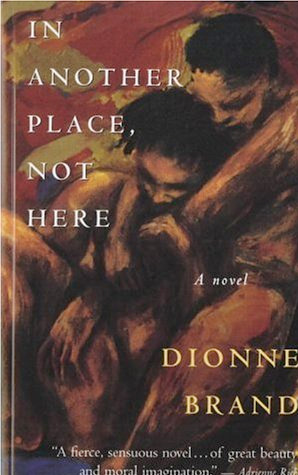

Casey reviews In Another Place, Not Here by Dionne Brand

For readers unaccustomed to the Black Caribbean vernacular that begins Dionne Brand’s 1996 novel In Another Place, Not Here—like me—there’s a bid of an initial hurdle to leap over to sink into this book. But trust me, it’s worth it; and sink in you truly do. Brand is an exhilarating poet and although this isRead More