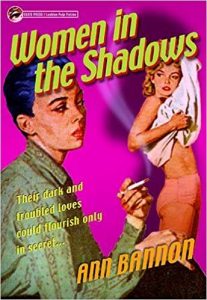

I’ve steadily been making way through the Beebo Brinker Chronicles, a classic lesbian pulp series by Ann Bannon, for quite some time. Women in the Shadows is the third book in that series and by far the most difficult to read so far.

This review, by nature of being for the third book in a series, contains some spoilers for the first two books. That said, let’s get into it.

Women in the Shadows picks up after the second book, I Am a Woman, and quite some time has passed. Laura and Beebo are living together in Greenwich Village, and both are very unhappy. Laura feels that she is falling out of love with Beebo, and Beebo is only holding on more tightly, which only pushes Laura further away. When Laura finds herself attracted to Tris, another woman, things start spiraling out of control.

Trigger warnings for this book include domestic abuse (physical and emotional), animal abuse, self-harm, and rape. These are also mentioned and briefly discussed in my review.

When I read lesbian pulp, I always come across parts that are uncomfortable to read. Some of the language used to talk about LGBTQ identities and people of color is jarring. Ideas about sex and consent are very different, too. By nature, pulp fiction is supposed to be sensational and shocking, and I think the effectiveness of the sensation and shock only grows larger as the years pass. Some of the uncomfortable themes are also due to outdated social norms and ideas. I definitely don’t read lesbian pulp with any expectations for it to meet my contemporary ideas, and I think that’s okay.

I expect a certain amount of discomfort when I read lesbian pulp. I think the discomfort is often worth the satisfaction of reading and developing a greater understanding of this fascinating part of lesbian literary history. Even with all of this in mind, I had a very difficult time reading Women in the Shadows.

I think the most difficult part of this book is domestic abuse, both emotional and physical. Primarily, Laura is the abuse victim, as Beebo constantly gaslights her, physically overpowers her, and emotionally manipulates her. If readers are meant to root for Laura and Beebo as a couple, I was definitely doing the opposite and rooting for her to get out of that situation as soon as possible. The abuse is truly hard to read, and anyone who can potentially be triggered by it should be cautioned.

Highlight for spoilers. A particularly uncomfortable scene is when Beebo fakes being assaulted and raped by multiple men, who also graphically killed her dog. Now, I say faked, but when this scene first occurs we read it from Laura’s perspective, and she believes it to be true, so it can be very triggering under the assumption that this truly happened to Beebo. We later find out that Beebo faked it to gain Laura’s sympathy in a play to keep their relationship and keep her from leaving. This means that Beebo beat herself, and also gruesomely kills her dog. Later, when a friend gives her a new dog, she kills that dog too. It’s not fun to read. It’s not entertaining. It’s just difficult.

In the edition that I read, there was an author’s note addressing some of her errors in writing this book, and ultimately, I read pulp with a grain of salt anyway, so I wasn’t entirely put off by what could be considered “problematic”. However, others may feel differently and have different reactions than I did. There is certainly triggering material in almost all pulp novels, but Women in the Shadows seems to have an extra dose, so please do read this with caution if any of the triggers listed at the beginning are not okay for you. Otherwise, this book is a part of lesbian history as all lesbian pulp is, and especially Ann Bannon’s works. That alone makes it worth the read to me, no matter how hard it was to get through at times. But… I highly doubt I will ever reread this.