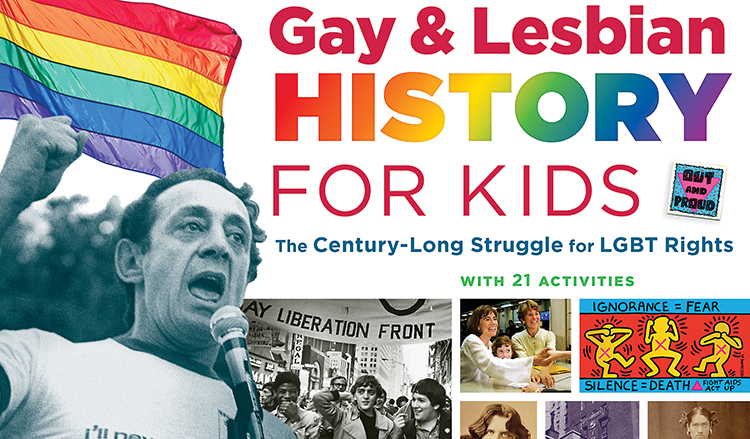

There isn’t a lot of nonfiction for young readers out there about LGBTQ people or issues. For this reason alone, Gay and Lesbian History for Kids: The Century-Long Struggle for LGBT Rights, with 21 Activities stands out. With just over 150 pages, tons of beautiful photographs, and a century of gay history, there’s nothing else like it on the market for children. Public and school libraries should stock it and let interested readers learn about the context and story of gay activism in the United States. There is nothing overtly sexually in this book and nearly all the language is totally school-appropriate, so there is little for adults to object over, except for the folks who are upset about the spotlight on gay history itself. The book also lists resources so interested readers can find out more.

Is it something you should buy for the kids in your own life, though? That depends. I’m a middle school teacher and a former elementary teacher, and I received a copy of this book for my class library in exchange for an honest review. I currently work at a school in the Bay Area with an active gay-straight alliance and a handful of out teachers, including me. While I was very excited for this book and think it would be great for some kids, it has limitations.

The biggest of these is that the intended audience is more unclear than it seems on the surface. The reading level is advanced, at least upper elementary if not middle school, but the tone is clearly for children, not young teens. Teens and tweens who see themselves as mature or who already have some awareness of LGBTQ history and politics may find it patronizing. Many sections struck me (and some of my volunteer eighth grade readers) as talking down to the reader. This wouldn’t be as noticeable to, say, a third grader but the vocabulary and writing style is beyond that of most third graders. A child would likely find it frustrating to read unless they are a very fluent reader with a great vocabulary or they are reading it with an adult. The activities are all for students in elementary school, some of them best for students in early elementary grades. These activities don’t add much to the book either. Gay and Lesbian History for Kids would have had a wider audience with an easier reading level, without activities, with “young people” instead of “kids” in the title, and/or with a little more faith in its readers.

It’s noteworthy to me that the title and subtitle don’t really line up in this book, which is reflected in the book itself. Bisexuals don’t get mentioned very much. Trans people and trans rights get more attention, but huge chunks of trans history in the 20th century are absent. Even the lesbian history sections are condensed to the point that I felt important parts of the story were missing. Part of this is just that summing up a century in the space allotted means things will be left out. Yet as a history buff, and history teacher, I know that what we cut for space is often as telling as the history itself.

Similarly, the book briefly explores homosexuality and gender variance in ancient history in ways that didn’t read as balanced to me. Africa’s left out of the early history section entirely and Asia’s section mentions only a gay emperor in China and a gender flexible Hindu god/dess. In reality, pre-colonial queer and trans history around the globe is really interesting! Many homophobic laws and cultural influences in Asia, Africa and the Americas are leftovers from European imperialism and colonialism. It’s fascinating to look at how that lingers. In some places globally there’s never been a large scale gay rights movement because queerness is more culturally normalized, even if that normalization occurs in flawed ways. I wish, if pre-modern LGBTQ history were going to be mentioned in a global context, it had been explored more deeply. The rest of the book is about LGBT history mainly in North America and somewhat in Western Europe. The bits about Two-Spirit Native peoples are all in the past but not the present, and queer and trans people are discussed in ancient cultures when the modern descendants of those places are never mentioned in modern history sections of the book. The attempt a global multiculturalism feels more like spice than substance.

Along those same lines I wish this book took a more intersectional approach. A featured picture in the book shows the first Annual Reminder in 1965, with Frank Kameny holding a sign reading “Homosexual American Citizens–Our Last Oppressed National Minority.” A similar idea later popped up unchallenged in a Larry Kramer quote from the 1980s. But obviously when we look back at the 60’s or the 80’s or even when we look at the U.S. today, we can see racism, sexism, ableism and other forms of oppression had and have devastating effects on people, that homophobia isn’t necessarily “the worst,” and that trying to pick a “worst” oppression isn’t really the point. The fact that gay white men thought that gay people were the last or most oppressed minority strikes me as pretty clueless. The idea that it’s possible to experience oppression and privilege in a variety of intersecting ways isn’t presented at all. It is a complex idea, but a valuable framework for people who may be reading about activist history for the first time.

Despite all the criticism, I am really glad to have this for my classroom. I absolutely think it should be in libraries for young people. I don’t think it should be the only book on LGBTQ history available, and I hope future authors fill the gaps. If you’re thinking of buying this book for an individual child or teen you know, consider their reading level, age, and how much support they’ll get reading it. If you’re there to bridge the gap between the tone and the reading demands, and ready to provide information about what’s left out, go for it. If not, you might want to read it yourself before you decide if it’s really right for the young person you have in mind.