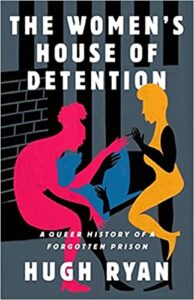

Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link

Since the days of lesbian pulp fiction, Greenwich Village has been seen as a gay hub, a refuge for queer people from all over the country. In this book, Hugh Ryan shows that part of the reason for that is because from the 1920s to 70s, it held The Women’s House of Detention, a jail/prison for women and transmasculine people, and many of the people held there were queer.

At first glance, this seems like a narrow focus typical of a very academic book. But as each chapter looks at the prison through the decades, we see how this is a microcosm of broad social issues at the time. The story of The Women’s House of Detention is the story of LGBTQ liberation, and it also illustrates how prison abolition is a necessity.

In the introduction, the author explains how he began this research believing prisons need serious reform, but after seeing how prison reform over the decades in The Women’s House of Detention has only ever resulted in larger prisons with more people packed into them, he now believes abolition is the way forward. The prison was first built with smaller cells so that prisoners would have more privacy, each with their own cell–and then years later, they started keeping multiple people in each. A hospital was added–and then years later, it was gutted to make room for more cells. Then a hospital was reinstated. Then it was gutted again. Any attempts at reform always deteriorated with time.

Each chapter looks at a few of the queer people imprisoned during that decade, telling their stories–at least, what we know of them. It’s a fascinating look into the horrors of the criminal justice system, past and present, as well as the no-win situations these people were put in. Many of them return multiple times, because once they had a criminal record, they had no legal means of making money.

Since each chapter focuses on personal stories as a window into the lives of queer women and transmasculine people during that time period in New York, it makes this accessible and readable. We also get a look into queer communities in each decade, including how the people in The Women’s House of Detention participated in Stonewall and previous protests, even if few people saw or heard about it.

The Women’s House of Detention itself is a complicated place for many of the people imprisoned there: the conditions were horrible, but they also found a queer community there.

I haven’t read as much queer history as I would like, but this is one of my favourite books I’ve read on the topic, and I highly recommend it. The discussion about prison abolition versus reform is relevant to the conversations we’re having today, and seeing a timeline of how this push and pull has played out over a 50-year time period is helpful background. Both for the personal stories and the overall message, you should definitely pick this one up.