Amazon Affiliate Link | Bookshop.org Affiliate Link

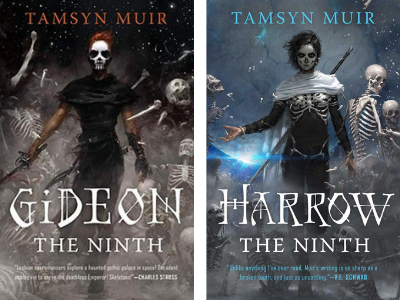

For Pride this month, I’m going to treat myself a little bit—I would like to talk about Gideon the Ninth and Harrow the Ninth, the first half of the Locked Tomb series by Tamsyn Muir (the half that’s been released, at time of writing). Now, if you like to read books about lesbians and also spend any time on the internet, you’ve probably been told to read these books already. They’ve gotten very popular over the last two years, and for good reason! But the ubiquity of Gideon the Ninth recommendations amongst queer women online is almost a meme at this point, and there are perfectly good reviews for both these books up on the Lesbrary already.

And yet, like everyone else I know who has read the Locked Tomb, I can’t stop thinking about it. But it’s not the goth-Catholic space necromancy worldbuilding, or the twists and turns of Muir’s buckwild mystery ride, or even the shockingly good humor peppered with actual internet memes that has its hooks in me. It’s something I don’t see a lot of people talking about, actually. It’s the fact that clearly, and yet so surprisingly, series deuteragonists Gideon and Harrow are written to be butch and femme.

Okay, granted, many people have called Gideon butch in the last two years, usually in regards to her being a strong, crass, bullheaded woman who is extremely and unapologetically into other women. And don’t get me wrong, this alone is worth celebrating—I read a lot of lesbian books, especially lesbian science fiction and fantasy books, and it is still painfully rare to see a lesbian protagonist that is undeniably masculine. But that isn’t all Gideon is. Gideon Nav is thoughtful and observant in her own way, and she has a surprisingly strong sense of justice for the society she grew up in. She also has a deep well of compassion and pity hidden beneath her anger and sarcasm. She wears irreverence and irony like armor to protect this emotional vulnerability, but cannot stop herself from leaping to the aid of others when they need help.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in Gideon’s relationship with Harrowhark Nonagesimus. Despite her objections to playing Harrow’s knight, Gideon slips into the role of protector and confidante naturally and quickly. No matter how much Gideon claims to hate the Reverend Daughter, her mind is constantly considering Harrow’s emotional state, her well-being, and her safety. And as they grow closer, Gideon starts taking her armor off. No one else gets to see the softness of Gideon’s heart—no one but Harrow.

On Harrow’s part, there’s a lot more to the vicious, uptight necromancer than meets the eye. This is my more contentious point by far, a realization that felt obvious to me but I rarely hear mentioned. Harrow is aptly named for what she has had to endure in life; she is a scarred, starving rat of a girl, deeply traumatized and burdened with unbearable expectations, dreadful ambitions, and untreated mental illness. She isn’t exactly the classic image of a femme lesbian.

And yet, there is so much about her that complements and contrasts with Gideon. Where Gideon is bold, brash, and courageous, Harrow is careful, resilient, and tenacious. Like Gideon, Harrow has a steady moral compass that points slightly off from what her parents, her peers, even her God says is right. Harrow, too, wears armor—not of dumb jokes and a fuck-you attitude, but of protocol, of social cues and cultural symbols, of robes and veils and make-up masks. But beneath it, just like Gideon, Harrow cares, more than she dares let on. The depth and intensity for how much she feels for Gideon, for her house, for even a sacred corpse is shocking when it finally comes out. She’s been forced to bare her steel all her life, but there is a vulnerability in her that only Gideon has the lived context to understand.

This is reinforced in the second book (slight spoilers ahead), when we get to see what a Harrow without Gideon would look like. She feels lost at sea, missing a vital piece of herself through which her resilience and determination slowly drains away. I know many people are into the perhaps-romantic tension between Harrow and Ianthe, but to me the main narrative purpose of that story thread was to showcase exactly why Harrow needs Gideon. Gideon and Harrow make each other better people, whereas Ianthe would make Harrow a far worse version of herself. And when it’s finally time for Harrow to admit her feelings for Gideon, it’s the heretical skeleton-raising goth space witch who has the softest, most tender and romantic passages in the series.

All in all, Gideon and Harrow are different in the most complementary ways, covering for the other’s shortcomings while encouraging each other’s strengths. They’ve both been through terrible experiences, but are also uniquely equipped to help each other process and move past them. In a horrific, hostile universe that seems corrupted to its very core, their love feels like the one light strong enough to defy it. And you can’t convince me that’s not butch and femme.

Content Warnings: violence, gore, character death (including murder and suicide), unstable/unreliable subjectivity. If you want to know more about the rest of the Locked Tomb’s content, I recommend you look up our other reviews of Gideon the Ninth and Harrow the Ninth.

Samantha Lavender is a lesbian library assistant on the west coast, making ends meet with a creative writing degree and her wonderful butch partner. She spends most of her free time running Dungeons & Dragons (like she has since the 90’s), and has even published a few adventures for it. You can follow her @RainyRedwoods on both twitter and tumblr.