You won’t catch me trying to write any novellas this November (respect for anyone who tries to write 50,000 words in a month, it’s just not in my plans any time soon), but I did read a few! To my mind, novellas occupy a challenging space when it comes to fiction. They need to be so much more tightly focused than a novel, and when done poorly they can feel anemic by comparison. On the other hand, novellas have vastly more space to breathe and play than a short story ever could; when done well, they’re like a satisfying main course next to a short story’s minimalist appetizer. The following novellas ran the spectrum in my opinion, though I think there’s something worthwhile in each of them for readers and writers of novellas alike.

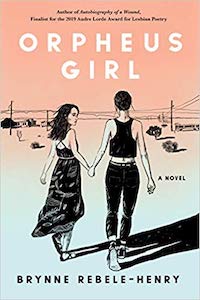

Orpheus Girl by Brynne Rebele-Henry is a very loose retelling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, set in mid-2000’s rural Texas. It is also absolutely brutal to read. The underworld here is a conversion therapy camp that lesbian teenagers Raya and Sarah are sent to after their relationship is discovered. Raya is bent on saving Sarah and leading them out of there, but the things they are forced to endure are not easy to stomach, especially with the knowledge that this sort of thing still happens today. Of the novellas I read this month, Orpheus Girl is the only one that I felt had more words to play with than was strictly necessary, and could afford to spend them luxuriously. I can tell that the author was primarily a poet before moving to fiction. Still, reading Orpheus Girl left me in a half-heartbroken haze—I appreciate books like these, but they’re the reason I generally stick to lesbian fantasy and sci-fi more than any other genre of sapphic fiction.

Content Warnings: homophobia, transphobia, child abuse, self-harm, suicide attempt, torture

Fireheart Tiger by Aliette de Bodard is a small, anxious story about finding agency while trapped in restrictive relationships. Princess Thanh and her kingdom of Bình Hải are stuck in several, be it with more powerful nations, former lovers, or even Thanh’s own mother. Fireheart Tiger is the shortest book here, and I felt like it struggled the most with the novella format. A large portion of this book is spent telling rather than showing, and the overall effect is that most of Fireheart Tiger feels like it is spent deep inside Thanh’s internal ruminations. Which isn’t to say that the situations it presents aren’t compelling; Thanh’s political predicament is a thorny one that presents no clear solution, likewise Thanh’s struggle to reconcile her troubled relationship with her mother and their cultural tradition of filial piety. However, Fireheart Tiger lost me at its treatment of the only overtly masculine sapphic character. I understand what Eldris is supposed to represent in the narrative—both the threat and unavoidable gravity of an imperial nation—but in practice it just feels like she was written like a man, which is a stereotype of masculine lesbians that I hate to see in any story.

Spear by Nicola Griffith is another loose retelling of old myths, this time a clever weaving of medieval tales regarding Peretur—also known as Perceval, Parzival, or Peredur—along with a handful of other Arthurian elements. Set in 9th century Wales, Spear is a bewitching read right from the beginning, steeped in that subconscious feeling of agelessness that only really good fantasy can instill. The magic is mysterious and wild, the people historically grounded and human; each familiar name and face feels appropriately placed, and yet the story itself felt gripping and fresh. It has a young butch disguising herself as a man (without slipping into questioning her gender), a tender and passionate romance between a knight and a witch, a special import given to both etymology and food—in short, it feels like this book was written just for me, and I wish it were about a million times longer. As much as I want more lesbian low fantasy like this in my life, though, I can admit that Spear is only as long as it actually needs to be. Should I try to write a novella after all? …Maybe next November. Maybe.

Samantha Lavender is a lesbian library assistant on the west coast, making ends meet with a creative writing degree and her wonderful butch partner. She spends most of her free time running Dungeons & Dragons (like she has since the 90’s), and has even published a few adventures for it. You can follow her @RainyRedwoods on tumblr.