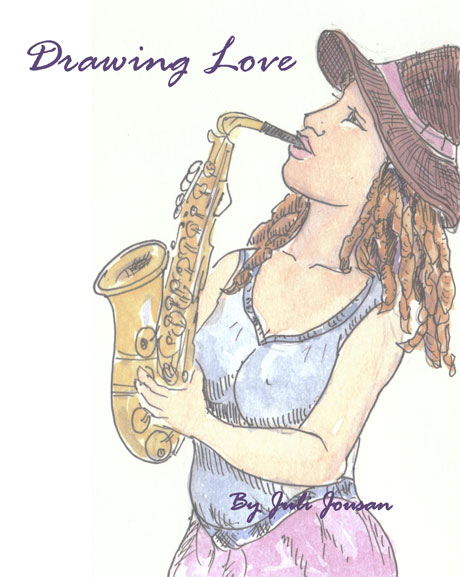

Drawing Love by Juli Jousan treads a fine line. It could easily seem overwrought or juvenile. Drawing Love alternates between the present and a description of the main character, Mo, having a dramatic high school relationship. By relating that in flash backs, and showing that Mo has moved on and grown up since then, it avoids being completely mired in the drama of the situation. Throughout the book are Mo’s drawings, which I don’t really feel comfortable commenting on, because I don’t really know enough about art to critique it. They are mostly line drawings.

Some of the writing, like the dialogue between Mo and her mother, seems a little stilted, but it manages to avoid that most of the time. Drawing Love offers a brief glimpse into a life, mostly showing a college relationship with the flash backs to provide context. There are lots of drawings, large font, and wide spacing throughout the novel, making it an easy 2 hour read.