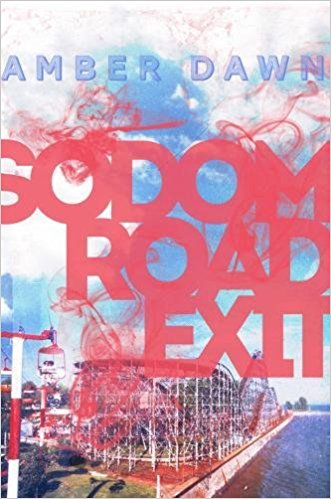

Buried under a mountain of debt, Starla Martin is forced to say goodbye to her life in Toronto and return to her hometown of Crystal Beach. To help her with her debt, her mother offers to find her a job with her at the local library, but Starla knows that just living with her mother will already be challenging enough. Instead, she finds a job at a local campsite, “The Point”, working the overnight shift. There, she finds herself involved not only in the lives of its residents, but also in a supernatural phenomenon unlike any she’s experienced before. And yet, Starla is not afraid. In fact, she is the exact opposite.

I was instantly drawn to this book because of its setting. It’s hard enough finding Canadian stories that aren’t set in the plains, but a queer ghost story set in Eastern Ontario? Colour me intrigued. In this aspect, the story did not disappoint. Everything about this story screamed Ontario, from the crappy local bus service, to the celebration of May two-four. Even though I’ve never been to Crystal Beach, or even Fort Erie, after reading this book I feel like I have.

The protagonist, Starla, took a bit of time to get used to. This is partially because for the first few chapters of the book, all we really seem to know about her is that she lives in Toronto, dropped out of college, and has a lot of sex. Her sexual partners are described as both male and female, which led me to assume that Starla is bisexual, and having the only personal characteristic of a bisexual character be that she has many sexual partners was not a very promising start. However, as the story unfolds you learn more about Starla, who she is, why she acts the way she does, what led her to the choices she made. She goes from a two-dimensional sex-addict to a three-dimensional traumatised woman, simply trying to live her life.

As for her sexual orientation, despite seemingly being attracted to men and women, Starla is often labelled a lesbian, though never by herself or her girlfriend. This can most likely be chalked up to the story being set in the 1990’s, when knowledge of all things queer was still pretty minimal. It is made very clear that Starla feels more attracted to women than she does to men, so it is also possible that she is a lesbian who is struggling with compulsive heterosexuality based on her past, though this isn’t delved into too deeply.

This is an incredibly heavy story, with characters suffering from such things as spousal abuse, alcoholism, suicide ideation, and past physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. The latter is described explicitly, as both Starla and her friend, Bobby, have experienced abuse in their past. Bobby’s past abuse is specifically relating to her identity as an Aboriginal woman, something I am happy that Dawn included and delved into. [minor spoiler] Starla’s abuse happened when she was a child, and it is implied that her mother was aware of it but did nothing [end spoiler]. As well, there is an incident near the beginning of the novel between Starla and a cab driver that does not read as consensual in the least. If any of these things trigger you, you may want to give this book a pass.

The supernatural element of the book was incredible. The ghost, Etta, is both a sympathetic and villainous entity. You feel for her, the way she was in life, and the horrible way she died, but at the same time you hate her for what she is doing to Starla and everybody around her. I adore characters who can be loved and loathed, as I find it such a tough line to walk. Dawn manages it flawlessly here.

I won’t delve too far into the love story of this book, because it’s something you need to experience by reading it to fully understand. Just know that it is perfectly crafted, and unlike any romantic plot I’ve read before.

Overall, Amber Dawn has crafted a wonderful supernatural drama, full of characters who feel so human, you’ll think they’re your friend by the end. She draws you, not only into their lives, but into their environment. By the end of the story, you will be dying to book yourself a ticket to Crystal Beach, hoping to experience even a hint of what the novel describes.