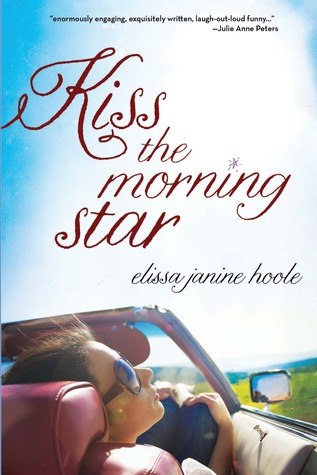

In Elissa Janine Hoole’s Kiss the Morning Star, Anna takes a roadtrip with her best-friend-for-years, Kat, to find proof of God’s love. It’s a few weeks before Anna’s 18th birthday, and a few months after her mom died in a house fire and her pastor father stopped preaching, and speaking altogether. A lesbian, Young Adult, coming-of-age novel centering on faith? you ask. Yep. And it’s good.

I was skeptical at first, waiting to get hit over the head with moralizing. But that doesn’t happen (excepting a couple less-than-ecstasy-inducing drug experiences and a nearly PG sex scene). Katy Kat and Anna babe, as they call each other, use Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums as a guide by choosing their next move with closed eyes and a finger on a random page. They get tattoos, get caught in a Mexico-bound bus full of missionaries stalled on train tracks, meet the shaman (a musician/spiritual leader), and have an encounter with a bear while backpacking. Along the way, Anna mourns the loss of her mother, tries to mend her relationship with her father via text message, begins to let go of some her burdensome fears and limiting routines, and recognizes that she is in love with Katy.

They find God subtly–the reader is left only to suppose they succeed–and falling in love with each other is a huge step of their journey. This sweet, teenage road novel is so satisfying I only wish I could have read it when I was a teen, but it’s just as fulfilling as an adult.