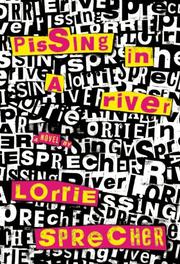

Throughout my reading of Lorrie Sprecher’s latest release, there was no denying the frustration — in fact, near torment — I endured in witnessing the chasm between what Pissing in a River is and what it could have been. One might equate the experience to an encounter with a woman who inspires boundless passion and devotion given qualities so rare that one wouldn’t think to pass up the opportunity to get to know her better and the realization that this same woman also possesses flaws so glaring that they are right up there with anyone’s top deal breakers. Oh, the agony of deciding whether to let yourself fall for what stands before you, as imperfect as it may be, or to walk away disillusioned, jaded that the potential recognized at the outset will never be fulfilled!

Amanda, the quintessential anglophile and aspiring expat, ventures to England initially as a student and years later on a tourist visa in order to track down the two women whose voices speak to her within her own head. Having been given diagnoses with varying degrees of validity over the years by mental health professionals who she believes were operating in accordance with their own agendas and biases, Amanda finds her symptoms abating as she encounters the physical manifestations of the voices she hears, Dr. Melissa Jones and a girl named Nick, with whom she becomes acquainted after intervening when Nick is raped in a dark alley late one night.

Thrust together in the aftermath of that trauma, the three women grow to find sanctuary within their friendship, providing support and understanding when they need it most. Whereas both Melissa and Nick are haunted by their experiences of sexual assault, Amanda grapples with messages internalized over years as a consumer within the mental health system. As is the case with many who struggle with psychiatric disorders, Amanda is sensitive to the emotions of others and thus endures feelings of guilt and shame, not only for arriving too late to prevent Nick’s rape, but also for injustices carried out around the globe. Without question, Amanda gleans a great deal of her identity from her appreciation of punk music as well as political activism and social advocacy.

I was impressed with the way the book addresses the often overlooked challenges to healing in the aftermath of an assault as well as the daunting task of navigating the internal and external obstacles presented by a mental illness. Pissing in a River boldly broadens the accepted definition of rape and promotes mental health parity, reducing stigma and improving access to treatment while allowing for greater compassion and acceptance. Lest I neglect to mention, Sprecher writes with sensitivity to the potential for fluidity within one’s sexual orientation, which I took to be empathic as well as astute.

Indeed, Pissing in a River has all the makings of an extremely influential, entertaining and thought-provoking work; however, it is also laden with less desirable elements that, for me, proved impossible to ignore. Many of the events, especially within the ass-kicking scenes, are not at all believable; and, primarily early on, so much attention is placed upon irrelevant details that the momentum and interest generated with regard to Amanda’s internal landscape are forever compromised. That being said, it was the multitudinous references to what band merchandise the characters are wearing and the incessant quoting of lyrics that did me in. (T-shirts/Sweatshirts are referenced 97 times.) The importance of punk music and culture to Amanda’s self-concept is abundantly clear without these tedious elements which halt all movement within the story. Even if it were intended as a reflection of Amanda’s OCD, there are certainly more effective means of communicating the impact of the disorder upon the various aspects of her life.

What prevents Pissing in the River from realizing its potential as a groundbreaking work are a lack of consideration for the integrity of the writing itself and the need of a heavier hand in editing. Not only does the novel, as it currently stands, serve as a disappointment to the reader who invests herself in the telling of Amanda’s tale, but there remains a profound sense that the characters themselves are slighted for their truth appears to be ruthlessly sacrificed for the sake of the author’s own. I can only hope that this work will see a second printing with revisions that allow it to live up to its most extraordinary potential.