Tag Archives: S. Andrea Allen

Stephanie reviews Her Sigh: A Lesbian Anthology by Victoria Zagar

As most of you know, I LOVE short story collections, so when I came across Her Sigh: A Lesbian Anthology by Victoria Zagar, I thought I’d give it a go. Short stories don’t get a lot of love in lesbian literature, (most folks want to read romance novels), so I’m always excited when I see that a new collection has been released.

To start, Her Sigh isn’t quite what I expected. Silly me, when I saw that it was an anthology, I thought it was a multi-author collection; it’s not. All fourteen stories are by Zagar, and they mostly have a similar theme: love. Zagar also works hard at creating dystopian/fantasy settings where love seems to conquer all, and in a few of the stories, it does.

For example, both “Sophie’s Song” and “Expiration Date” focus on post-nuclear war society, although neither story gives us much information on the wars, or how far into the future the stories are set. “Expiration Date” is a rather interesting take on family in an era where population control is paramount to society’s existence. In order to quell married couples’ desire for children, the government has come up with a novel solution, the Realichild, where couples are allowed to raise a child for limited period of time. Revealing anything more might spoil the story, but I really liked the way that Zagar normalizes the lesbian couple, but problematizes the ways in which the nuclear family (no pun intended) is still central to a happy family.

A few of the other stories read a bit like fairy tales or fables: a princess must decide whether or not to marry a prince when her true love is a female knight; a young woman seeks an arranged marriage to save her family, but is in love with the village seamstress, and another young woman realizes that she is the reincarnation of an ancient creature’s lover.

Overall, the collection is a solid read although there were a few times when I just rolled my eyes. How many cabins in the woods can there be in lesbian la-la land? How many old world villages? Additionally, a couple of the stories felt a bit rushed. Short stories are difficult to write, so I understand that everything can’t fit, but I do think that if you’re going to create dystopian societies, space colonies, or old world villages, then make sure that they don’t all feel the same, otherwise your readers might become bored. Although this wasn’t really my cup of tea, if you like lesbian romance with a flair for the otherworldly thrown in, this may be the collection for you.

Stephanie reviews Don't Explain by Jewelle Gomez

Don’t Explain is a collection of short stories by Black lesbian author, activist, and philanthropist Jewelle Gomez. Most widely known for her Black lesbian vampire novel The Gilda Stories, Gomez’s Don’t Explain is a collection of nine stories that employ rich, sensual, language to introduce readers to several carefully constructed characters whose stories set our minds and bodies afire. Although the collection was written in 1998, the stories are as poignant and relatable as they were when the book was published nearly twenty years ago.

For example, my favorite story in the collection, “Water With the Wine” is a new take on an old trope, the May-December romance. Gomez carefully deconstructs the most commonly held notions about romance between older and younger lesbians, and posits another reality for the women in her story. Alberta and Emma meet and become involved at an academic conference; however, differences in age, class and race threaten to destroy their budding relationship. Gomez deals sensitively and honestly with these issues and deepens our understanding of what it means to fall in love after the blossom of youth.

“White Flower” is a chronicle of desire, not quite erotica, but pretty close. Luisa and Naomi “can’t have a relationship, it’s too consuming too everything,” so their meetings are infrequent but filled with all of the lust and passion that two women can share. This story will leave you panting, it will also leave you wondering at what point the unbridled desire turns to obsession and manipulation.

In “Lynx and Strand,” the longest story in the collection, Gomez forays into the genre where I believe she does her best writing, speculative fiction. To put it simply, speculative fiction is not quite science fiction, not quite fantasy, but an imaginative blend of the two genres, and in this story, explores what it means to live in a future where same-sex relationships are still policed by the state. Here, Gomez tackles issues of futuristic state governments, homophobia, body art, and what it means to truly become one with your partner. The story is timely, some might say prophetic, because even though it was written nearly two decades ago, LGBTQ persons’ right to bodily autonomy is still being challenged, even threatened, in 2016.

For those familiar with Gomez’s The Gilda Stories, “Houston” offers a new chapter into the life of her Black lesbian vampire and offers a provocative look at what it means to be humane when you actually aren’t human at all.

All of the stories in this collection are sensitive, sensual, and offer a pleasant alternative to “mainstream” lesbian fiction. The collection also focuses on Black women’s experiences, and this is what truly sets it apart from most of the lesbian fiction on the market today. The collection is short, only 168 pages long, but each of the stories offers entrée into the life of Black women, mostly lesbian, that illuminates the complexity of our lives and the power of our loving. If you have not had an opportunity to read any of Jewelle Gomez’s work, start with this collection and I am certain that you will want to read more!

Stephanie reviews The Dawn of Nia

I’m always hesitant to read books by people that I know personally, because I know at some point they’ll ask me what I thought, and I know that if I don’t love it, I’ll have to figure out how to say that without ruining the relationship. In this case, I can say without reservation that I did indeed love The Dawn of Nia. Let me count the ways:

I liked that fact that The Dawn of Nia is focused on family relationships and the ways in which secrets can devastate families or force them to reckon with their past misdeeds. Nurse Nia Ellis is a single, attractive, Black lesbian who has recently lost her friend and mentor Pat to cancer. What Nia doesn’t know is that Pat had a secret, and that Pat’s secret is going to change her life. This first secret is revealed right after Pat’s funeral, which Nia attends with her best friend Jacoby, and the novel just explodes with drama from there. It’s a bit of a challenge to write about this novel without giving too much away, but just know that secrets, lies, betrayal, and a $350,000 estate are at the crux of the story.

I was also really impressed with the character development. All of the characters in this novel are deeply flawed. The protagonist Nia is the poster child for bad decision-making. At one point while reading I nearly threw the novel across the room. I found myself yelling at Nia: “Girl what the heck are you doing? You know that Kayla is going to start some mess!” But I couldn’t stop reading. Jacoby, Nia’s best friend, is the epitome of male privilege. To put it nicely, he’s an ass, and there were times when I just couldn’t figure out why Nia remained friends with him. Tasha, another close friend, is always hooking up with Ms. Right now, instead of waiting on Ms. Right. Even Nia’s parents have issues that span their 30-year marriage. The other women in Nia’s life, her ex-girlfriend Kayla, and new love interest Deidra, are connected in ways that are impossible to untangle, even though Nia tries her best to keep the women apart. It is a testament to Cherelle’s skill as a writer that not only was I able to keep up with all of these characters, but I found myself rooting for some to succeed, and hoping that karma would catch up with others.

The novel has excellent pacing. It never felt rushed or to seemed to drag. I was always anxious to get to the next chapter to see what was going to happen next. However, my only critique of the novel is that it probably could have been just a few pages shorter. A couple of scenes at the end just didn’t seem necessary.

Finally, at its core, The Dawn of Nia is a story about love: what do you do when your heart has been broken but you want, sorely need, to give love another chance? How do you keep your past mistakes from ruining your future? Can any relationship survive lies and deceit? Why do lesbians move in with each other so quickly? I’m generally not one for reading romance, but I loved every minute of this story, even as it was driving me crazy. If you like your romance spiked with a bit of family drama, this is definitely the novel for you. Cherelle is a masterful storyteller and this novel is a welcome addition to the growing canon of contemporary Black lesbian literature.

Trigger warnings: Mild violence, brief mention of sexual abuse

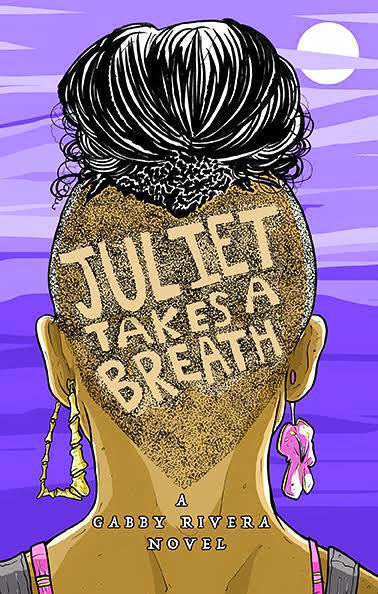

Stephanie reviews Juliet Takes a Breath by Gabby Rivera

I can’t remember the last time I read a book in two days, but I have to admit that once I started reading Juliet Takes a Breath, I couldn’t put it down. I laughed, cried, raged, and wondered at Juliet’s antics and her naiveté, and fell more in love with this book every time I turned the page.

The novel’s protagonist is Juliet Milagros Palante, a 19-year-old Puerto Rican college student from the Bronx. She’s pretty sure she’s lesbian, and has been reading her feminist idol Harlowe Brisbane’s Raging Flower: Empowering Your Pussy by Empowering Your Mind, to help her learn more about feminism as well as her own sexual orientation. On a whim, Juliet writes Harlowe a letter and the author responds with an invitation to Portland to work as her intern for the summer. After an awkward dinner where she comes out to her family, Juliet hops on a plane to Portland to try to figure it all out.

Harlowe is every white lesbian feminist hippie stereotype rolled into one. I have a feeling this was purposeful, since a good portion of the latter half of the novel is spent questioning Harlowe’s intentions and the one egregious act that sends Juliet away from Portland for a few days. Still, Rivera’s characterization of Harlowe is hilarious as well as fodder for serious eye rolling. For example, when Juliet starts her period early, Harlowe tells her “My cycle is probably going to mentor yours.” Another gem: After Juliet experiences a few intense days, Harlowe declares, “Not talking about a break-up can totally lead to a yeast infection.” There’s more of this, but again, I think the stereotyping is intentional; Rivera’s purpose is to question the universality of feminism and sisterhood, and Harlowe is the vessel through which she works through these issues in her novel.

My favorite character is probably Juliet’s cousin Ava, who calls Juliet out on her obtuseness after she flees to Miami to process what happened at Harlowe’s reading at the bookstore in Portland. My favorite line: “Girl, c’mon you could have realized that she was some hippie-ass, holier-than-thou white lady preaching her bullshit universal feminism to everyone.” Welp. I have to admit, I’d been waiting for someone to say this to Juliet the entire novel. Regardless, Ava helps her to understand that queer Brown communities just might be the place where she can be her entire Puerto Rican, feminist, queer, curvy, self. Ava takes Juliet to the Clipper Queerz party, a Black and Brown people only space, where it’s “less about there being ‘no white people’ and more of a night for us to breathe easier.” Black and Brown folks are often accused of being exclusionary when we carve out spaces for ourselves, and Rivera does a great job of making it clear why these spaces are necessary for our mental, emotional, and yes, physical health.

I really loved this novel. However, there were a couple of times where I shook my head in disbelief as I was reading. For example, while Juliet’s naiveté is mostly endearing, there are places where it’s a bit over the top. How has she not heard of Chicana feminists Cherríe Moraga or Gloria Anzaldúa? Even her white feminist lesbian girlfriend Lainie seems to have a better grasp of Latina activists than Juliet, given her knowledge of Puerto Rican history and Lolita Lébron. I was also a little troubled by the scene where she bleeds all over the bed at Harlowe’s house. Let me be clear, the bleeding wasn’t my issue, but who on earth tries to clean blood off of sheets using deodorant? Juliet is 19, not nine, so it seems unlikely that she wouldn’t know how to get a bloodstain out of her sheets. There were a couple of other minor snafus as well, (the novel was preachy in places, and we don’t know that the novel is set in 2002 until halfway through), but these issues don’t detract much from the story.

All in all, this novel is a welcome addition to lesbian literature that focuses on Latina experiences. It’s a “fish out of water” type bildungsroman, with a Queer Brown twist. Does Juliet figure it all out in Portland? Is she able to reconcile all the parts of her intersectional identity? Can all women truly be sisters? I can’t promise that Juliet Takes a Breath offers tidy answers to any of these questions, but I can promise that you’ll have the time of your life finding out.

Stephanie Recommends Five Classic Black Lesbian Books You’ve Probably Never Heard of But Need to Read

I recently attended a literary conference focused on lesbian literature and was shocked at how many attendees didn’t know anything about Black lesbian literature outside of two or three authors. Most were familiar with Jewelle Gomez’s The Gilda Stories, which celebrated its 25th anniversary this year, and Audre Lorde, the consummate Black lesbian poet, but that was about it. Full disclosure: I wrote an entire dissertation on the marginalization of Black lesbian literature, so I might know more about Black lesbian books than the average lesbian literature lover. Still, here are a few titles that you’ve probably never heard of, but that you should definitely read. This month I’ll discuss five titles, and I’ll finish up the list later this year.

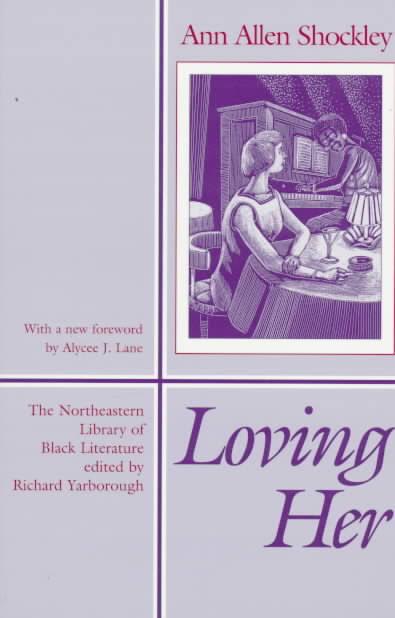

1. Loving Her (1974). Ann Allen Shockley is generally hailed as the first Black lesbian novel published in the United States, i.e., the first novel written by a Black lesbian with a Black lesbian protagonist. Loving Her, while at times overly didactic, is the novel upon which the Black lesbian literary canon is built. The novel’s themes are overtly political, mostly in relation to the Black Nationalist and feminist rhetoric of the time, but these topics are still relevant today, and particularly given our current political climate. The novel centers on Renay, a working class Black musician married to the abusive, failed football star, Jerome Lee; and Terry, the rich white woman writer who falls in love with her. Loving Her goes back and forth in time, as it relates the story of how Renay and Terry met, as well as the challenges they faced as a couple. There is a bit of drama, but you’ll have to read the novel to find out what that is! As mentioned earlier, the writing can be a bit heavy at times, but this book is an excellent look at how one writer represents an interracial lesbian relationship.

1. Loving Her (1974). Ann Allen Shockley is generally hailed as the first Black lesbian novel published in the United States, i.e., the first novel written by a Black lesbian with a Black lesbian protagonist. Loving Her, while at times overly didactic, is the novel upon which the Black lesbian literary canon is built. The novel’s themes are overtly political, mostly in relation to the Black Nationalist and feminist rhetoric of the time, but these topics are still relevant today, and particularly given our current political climate. The novel centers on Renay, a working class Black musician married to the abusive, failed football star, Jerome Lee; and Terry, the rich white woman writer who falls in love with her. Loving Her goes back and forth in time, as it relates the story of how Renay and Terry met, as well as the challenges they faced as a couple. There is a bit of drama, but you’ll have to read the novel to find out what that is! As mentioned earlier, the writing can be a bit heavy at times, but this book is an excellent look at how one writer represents an interracial lesbian relationship.

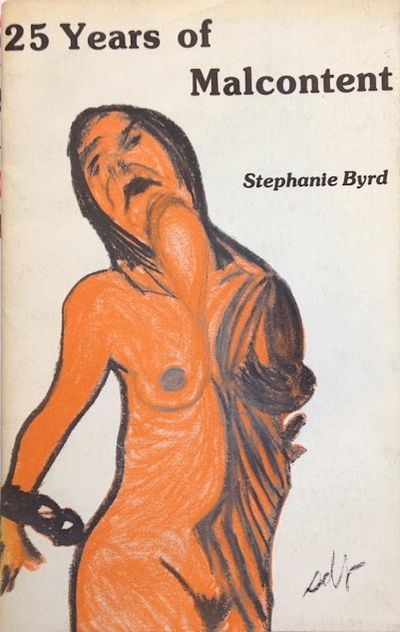

2. 25 Years of Malcontent (1976) and A Distant Footstep on the Plain (1983). Stephania (Stephanie) Byrd’s poetry centers the experiences of Black lesbians in the early years of the feminist movement. She writes of communes, the danger of being an out lesbian, as well as the joy she finds in communities of women who love women. You’ve probably never heard of her, but her poetry is not to be missed. The imagery is at times a bit stark and gritty, but that speaks to the veracity of her perspectives on Black lesbian life. [Available to download for free here.]

2. 25 Years of Malcontent (1976) and A Distant Footstep on the Plain (1983). Stephania (Stephanie) Byrd’s poetry centers the experiences of Black lesbians in the early years of the feminist movement. She writes of communes, the danger of being an out lesbian, as well as the joy she finds in communities of women who love women. You’ve probably never heard of her, but her poetry is not to be missed. The imagery is at times a bit stark and gritty, but that speaks to the veracity of her perspectives on Black lesbian life. [Available to download for free here.]

3. Black Lesbian in White America (1983). Anita Cornwell was calling out patriarchy, homophobia, and racism before most of us were born. She was a lesbian separatist, which may have made her unpopular in Black as well as some lesbian and feminist communities. This collection of essays is important, though, because she was clearly invested in writing about the experiences of women and creating a world where all women could be free. She was also one of the only Black lesbian writers to publish essays in Negro Digest and The Ladder. Check her out!

3. Black Lesbian in White America (1983). Anita Cornwell was calling out patriarchy, homophobia, and racism before most of us were born. She was a lesbian separatist, which may have made her unpopular in Black as well as some lesbian and feminist communities. This collection of essays is important, though, because she was clearly invested in writing about the experiences of women and creating a world where all women could be free. She was also one of the only Black lesbian writers to publish essays in Negro Digest and The Ladder. Check her out!

4. For Nights Like this One (1983). Becky Birtha’s collection of stories explores issues of loss, family, motherhood, and acceptance in lesbian communities, and like Ann Allen Shockley, she also wrote stories that included interracial relationships, mainly between Black and white women. One of my favorites is “Babies” which is about a woman who longs to have a child, but gives up that dream to be with the woman she loves. It may seem ridiculous now, but at the time, many lesbians considered having children complicity in patriarchal system, and they wanted no part of it. Don’t believe me? Visit your local library and check out a few books on lesbian separatism. More than anything, this collection of short stories reveals the myriad ways in which Black lesbians experienced life and love, and although not all of the stories have happy endings, one gets the sense that Birtha’s lesbians are unafraid to face life on their own terms.

4. For Nights Like this One (1983). Becky Birtha’s collection of stories explores issues of loss, family, motherhood, and acceptance in lesbian communities, and like Ann Allen Shockley, she also wrote stories that included interracial relationships, mainly between Black and white women. One of my favorites is “Babies” which is about a woman who longs to have a child, but gives up that dream to be with the woman she loves. It may seem ridiculous now, but at the time, many lesbians considered having children complicity in patriarchal system, and they wanted no part of it. Don’t believe me? Visit your local library and check out a few books on lesbian separatism. More than anything, this collection of short stories reveals the myriad ways in which Black lesbians experienced life and love, and although not all of the stories have happy endings, one gets the sense that Birtha’s lesbians are unafraid to face life on their own terms.

5. The Black and White of It (1980). Ann Allen Shockley’s collection of short stories offers up snippets of lesbian life in the late 1970s. The stories examine issues of loneliness, internalized homophobia, and racism, and more often than not, lesbians living in the closet. A white college professor falls in love with her out graduate student, but can’t free herself from the closet to make the relationship work. A Black politician rejects her lover because she refuses to disavow her lesbian identity. While several of Shockley’s lesbians lead droll, closeted lives, they provide a window through which readers can experience what it might have been like to be lesbian in the latter part of the 20th century.

5. The Black and White of It (1980). Ann Allen Shockley’s collection of short stories offers up snippets of lesbian life in the late 1970s. The stories examine issues of loneliness, internalized homophobia, and racism, and more often than not, lesbians living in the closet. A white college professor falls in love with her out graduate student, but can’t free herself from the closet to make the relationship work. A Black politician rejects her lover because she refuses to disavow her lesbian identity. While several of Shockley’s lesbians lead droll, closeted lives, they provide a window through which readers can experience what it might have been like to be lesbian in the latter part of the 20th century.

Black lesbian literature as a genre has grown since these titles were first published, and there are literally hundreds of titles now available that readers can choose from. However, I think it’s important for readers to know that Black lesbians have a literary history too. All of these authors are still alive, and some are still writing. Shockley published her last book, Celebrating Hotchclaw, in 2005; and Birtha is the author of several children’s books. The next time you’re in the mood for a little classic lesbian literature, check out one of these titles. And the next time you’re at a conference or book festival and someone says they don’t know anything about Black lesbian literature, tell them about these amazing writers!

S. (Stephanie) Andrea Allen

sandreaallen.com

Twitter: @S_Andrea_Allen

Lez Talk: A Collection of Black Lesbian Short Fiction

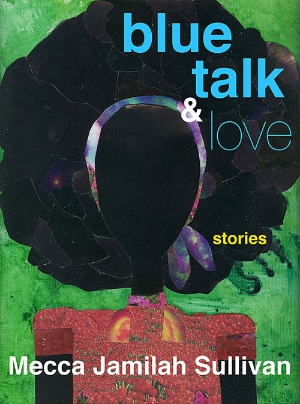

Stephanie reviews Blue Talk and Love by Mecca Jamilah Sullivan

Trigger warnings: Rape threats, mild violence, fat-shaming.

As soon as this book was released I knew I had to have it. Stories about Black queer women written by a Black queer woman? Yes, please! I was a little worried that I wouldn’t connect to them; they are all set in and around New York City, a place I’ve only visited once as a kid. It is a testament to Sullivan’s skill and talent that I was immediately drawn into this book. Not only that, her vivid descriptions of various part of New York made me feel as if I were right there with her characters. Indeed, I could smell the smoke and coconut oil in Earnestine’s father’s hair in “Blue Talk and Love,” the second story in the collection. Still, the specificity of the locales might alienate some readers as it draws in others.

The first story in the book, “Wolfpack” is drawn from real-life events: the trial and subsequent conviction of several young Black lesbians charged with stabbing the man who had threatened to rape them. The story begins with a directive: “This is a story that matters, so listen.” Those of us who remember this event are immediately drawn into this story, which retells the events of that summer night from several perspectives. The voice that resonated with me the most was Verniece’s (oddly spelled two different ways in the story). She tells her story with a quiet resolve: her desire to become a mother, her love for her girlfriend of two years, as well as her constant battles with her mother over her sexual orientation. “Wolfpack” is heartbreaking as well as anger inducing. Black lesbians are all too familiar with how attempts to protect ourselves from harm are often met with backlash. The judge that sentences these women suggests that they should have ignored the “I’ll fuck you straight,” as if those words didn’t imply an impending action. Sullivan does a wonderful job of transporting us back in time to that summer night, and in doing so, begs the question, what right do Black lesbians have to defend themselves from bodily harm?

Another favorite is “A Magic of Bags.” Sullivan transports us to a starkly different section of New York, that of the upper-middle class world of the Harlem Grange Homeowners’ Council, where “Most of the Grange’s young people spent their free time hopping subway turnstiles on the way home from their private schools, smoking looses in Riverside Park in feeble defiance of authority, plotting futures with one-another, most of which ended with masters’ degrees from MIT and expensive wedding receptions in opulent hotels downtown.” The story’s protagonist, Ilana, is alienated from this world, even her mother tries her best to maintain her place in it. Ilana is large and strange (she carries a bag of broken baby dolls wherever she goes), and sees herself as gifted, although it is not altogether clear the specific nature of her gifts. The story meanders a bit, as Ilana’s main purpose is to cause trouble for folks that she sees as victims of “horizontal thought.” This includes her mother, the women in the neighborhood, and her one friend, DeShawn. Still, Ilana’s keen observations on the trappings of domesticity and upper middle-class Black life are what make this story so interesting. I was a bit disappointed in the ending, as I feel that Sullivan might have missed an opportunity to push Ilana out of her comfort zone.

Other stories in the collection include “Saturday,” where eight year-old Malaya is forced to attend a weight loss support group with her mother because she has fallen off of the program wagon. Malaya daydreams of French fries and eats cold Chinese food in her room at night, yet often dreams of one day waking up “with a lightness and a spring.” Me-Millie and Me-Christine are the conjoined twins in “A Strange People,” sisters searching for a show that will accept them after their former slave-owner dies. The story offers keen observations on race, (dis)ability, performance, and desire in the 19th century.

Most of the stories in this collection focus on Black and brown bodies, queer in their sexual orientation, size, ability, and often a combination of all three. Sullivan reminds us that fat queer bodies are often the objects of ridicule and pain, but that they also are sites for joy and self-acceptance. We want, no NEED more from this writer.