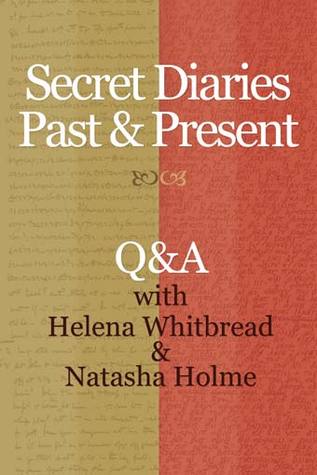

In 2013, British writer and academic Helena Whitbread and diarist Natasha Holme (a pseudonym), met to discuss a subject of mutual interest: diaries written by lesbians in original code. Aside from investigating the connection between two diarists, as stated in the title, highlights include early and adult sexuality, preservation and publication, and obsessive writing. The similarities and differences presented over the course of the book provide a fascinating insight into how connected these women are despite great distances of time, social status, and solitary endeavors.

By the time the authors of Secret Diaries at down to talk in Brighton, Helena had spent over thirty years exploring the life of fellow Halifax native, Anne Lister (1791-1840). Anne played many roles over the course of her life: businesswoman, landowner, lifelong learner, lover, and friend. As of this writing, she is also considered the first modern lesbian. The more personal sections of Anne’s journals are coded with what she referred to as “crypthand”; while on the other side Natasha shrouds every single entry, no matter how mundane, in code. Thanks to Whitbread’s unflagging scholarship and promotion, Anne’s journals have been added to the United Kingdom Memory of the World Register for documentary heritage of UK significance in 2011. Whitbread’s in-depth knowledge of Anne Lister’s life allows her to act as a sort of intermediary in the discussion.

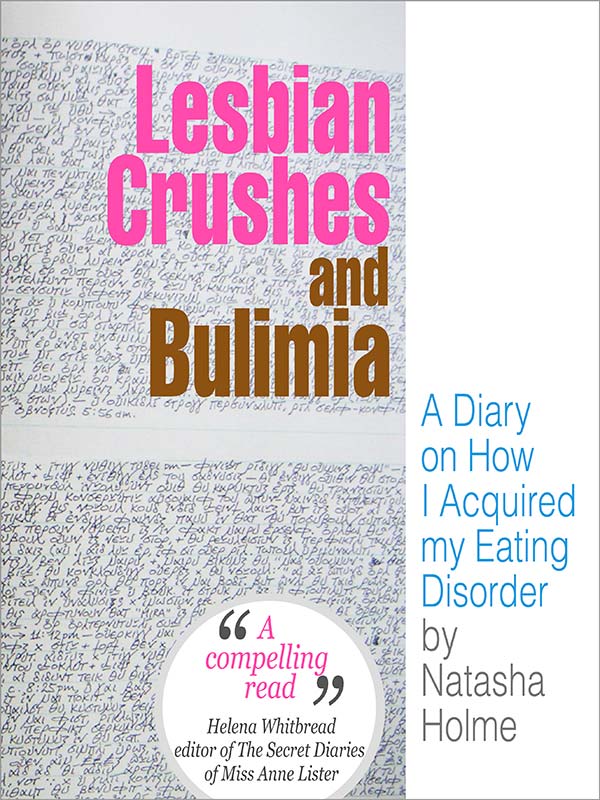

Co-author Natasha Holme was born in England in 1969 to middle class parents. Her experiences growing up with a dogmatic Christian father and volatile mother had a long lasting influence on the formation of her identity and relationships. Diaries offered a safe harbor for her thoughts and questions. Many folks find the same kind of comfort and sense-making afforded through journaling.

One point that strikes me is how the act of creating and the existence of physical copies have allowed this conversation to take place. Think about all of the tweets, Facebook posts, blogs, diaries, and other forms of communication you’ve created and all of the people with whom you’ve interacted. Think about people two hundred years from now. What kind of conversation will you facilitate through your private and public recordings? Anne Lister’s contribution to this book is unintentional, while Holme has published her diaries and thoughts on the diaries.

Natasha discusses her compulsive need to record every aspect of her life in great detail. Every entry is in code. As a teen and young adult, she often squirreled herself away to work at the laborious task of writing down conversations, activities, and thoughts. Over the course of her life, Natasha has written nearly nine million words. I am amazed at the energy and time she has devoted to her diaries. I have written in journals off and on over the years, but have never reached the consistency Natasha has demonstrated in memorializing her life. Natasha eventually edited and published three volumes from diary entries written in the 1980s to the early 1990s.

Anne Lister, on the other hand, did not have such safeguards against damage or loss. On at least one occasion, a diary had gone missing in transit. Thanks to whatever wonderful combination of factors (the secure hole in the wall she hid the diaries in, atmospheric conditions, lack of fire, etc), her personal accounts survived centuries and censorship. Who knows how many stories have not survived time? It further emphasizes how important it is to not assume that what we are aware of is the sum total of the human story. LGBT+ stories are especially vulnerable to loss; their existence and publication is essential.

Despite its brevity, Secret Diaries offers readers with a lot to mull over. The multiple vantage points from which Whitbread and Holme discuss the diaries inspires further questions, making it a great fit for book clubs. I have been sitting with this book for nearly a month and am still chewing on the nuances of coded identities and the interconnectedness of our stories. If you need to take the long view of history, especially now, add this title to your TBR shelf.

You can read more of Julie’s reviews on her blog, Omnivore Bibliosaur (jthompsonian.wordpress.com)