Have you been on the internet at all in the past two weeks? Yes? I’m guessing the cover of this book probably looks familiar to you. If not, try it in red:

That’s right: we’re talking about gay marriage! Marriage equality! A hot topic for around the world right now. While we won’t hear the US Supreme Court’s verdict until June, that certainly isn’t going to stop the internet from deliberating.

Speaking of which, have you seen this one?

Or maybe this one?

They’re symbols being posted, generally, by queer people who don’t support gay marriage or the HRC. When I first saw these symbols making the rounds, I admit – I was baffled. So I did what I always do. I bought some books.

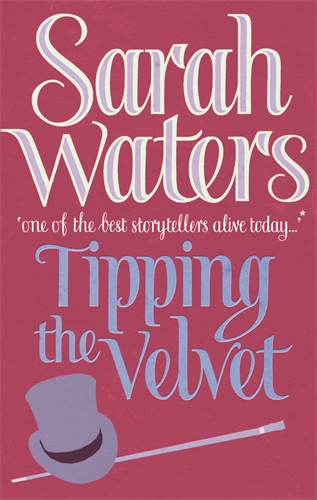

Virtual Equality: The Mainstreaming of Gay & Lesbian Liberation by Urvashi Vaid begins with a history lesson on gay political activism in the United States. Vaid writes,

“Throughout the history of our resistance to prejudice, gay people have clashed over a fundamental question about the overall goal of our movement. Are we a movement aimed at mainstreaming gay and lesbian people (legitimation), or do we seek radical social change out of the process of our integration (liberation)? Gay and lesbian history could be read as the saga of conflict between these two compatible but divergent. Legitimation and liberation are interconnected and often congruent; the former makes it possible to imagine the latter. But our pursuit of them takes different roads and leads to very different outcomes.”

Today, proponents of legitimation argue to the straight world that gay people are just like straight people, with the one small difference of who we are attracted to. They lead the fight for gay marriage, arguing to straight people that we are merely a minority, and that prejudice against us is irrational and unconstitutional.

Proponents of liberation, on the other hand, often believe that marriage is part of an oppressive sexual and political order. They argue that vast set of protections available to married people should also be available to single mothers, unmarried couples, single people, etc. Many feel that gay marriage should not be the top priority for the LGBT movement and would prefer to push for broader social change, in which “racism, homophobia, sexism, economic injustice, and other systems of domination are frankly addressed and replaced with new models.”

Of the two camps, Vaid is more of a liberationist, but certainly not an unquestioning one. Throughout the book, she deliberately lays out the limitations of both approaches. (Legitimation: elitist, preoccupied with single-issue politics, tends to leave many groups behind, does not make society more just. Liberation: idealistic and impractical, slow moving, not easy to relate to, tends to be disorganized.) She sternly calls out those making personal attacks, and the movement’s tendency to tear down our political leaders. At the book’s conclusion, Vaid calls for a new understanding among gay people, and for more debate among all political sides in the LGBT movement.

Although Virtual Equality was published in 1995, Vaid’s analysis is relevant, and indeed, anticipated many of the issues that the movement now faces two decades later. Her clear-eyed analysis of the supremacist right as a totalitarian regime is one I believe has only increased in relevance over time. So, too, her exploration of the economy of queerness, with the queer as consumer, and its corollary, the selling of gayness.

One other prescient point that I thought Vaid articulated particularly well is why the “born this way” argument is misleading and ultimately not politically advantageous for LGBT people. She writes,

“Homosexuality always involves choice – indeed, it involves a series of four major choices: admitting, acting, telling, and living. Even if scientists prove that sexual orientation is biologically or genetically determined, every person who feels homosexual desire encounters these four choices.”

Further,

“Because we choose to engage in gay behavior, says the right, we are not entitled to legal protection. Gay activists most frequently respond to this argument with an assertion that homosexuality is innate. … But in doing so, we radically limit the original reach of our political movement. Where we once sought to free the homosexual potential in everyone, by making it safer to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual, we now assert the conservative view that all we want is the freedom to be our biologically determined selves. History shows that the shelter of biology has never protected a people from persecution. The right does not care that we were born gay; they object to us because we are not straight.”

I like to imagine how differently her anthem might have turned out if Lady Gaga had read this book before penning her pop hit. Or how much further we might be if this book was required reading for every LGBT person about to enter a leadership role. Or what would happen if every Facebook activist changing their profile picture were to read this book. (Do our allies really understand the full historical weight of the symbols they’re using? Do we? I know I didn’t.)

I have a lot of respect for the work Vaid did as the director of NGLTF, and her decades of queer activism. If you’re even remotely interested in LGBT history, involved in social activism of any kind, or just want to put political discussion about LGBT issues into context – I can think of no better source than Urvashi Vaid and Virtual Equality. I highly recommend this book to you.

Bonus: for further reading, Vaid just put out a new book called Irresistible Revolution: Confronting Race, Class and the Assumptions of LGBT Politics. I’m excited to pick it up.